Painting as a Scaffold

Lately, I’ve been struggling to find an occasion for writing about art. Because I work at a gallery, my schedule makes it nearly impossible to see shows unless I manage to catch the opening, at which the art will normally be obscured by crowds of chatting people looking away from the walls at each other. So reviews are hard to muster. And essays need time to gestate. Ideas only reveal their place in the constellations of thought slowly, after many repeated encounters. But what of these encounters — the fragments of thoughts-to-be? Maybe they have something to offer as they percolate through the mind, not fully formed. Why not spit them out to see what they are and what they might become? The process of thinking might thereby be clarified, or at least laid bare for what it is: the groping of shadows by shadows. “All theory is gray,” so recognized Goethe.

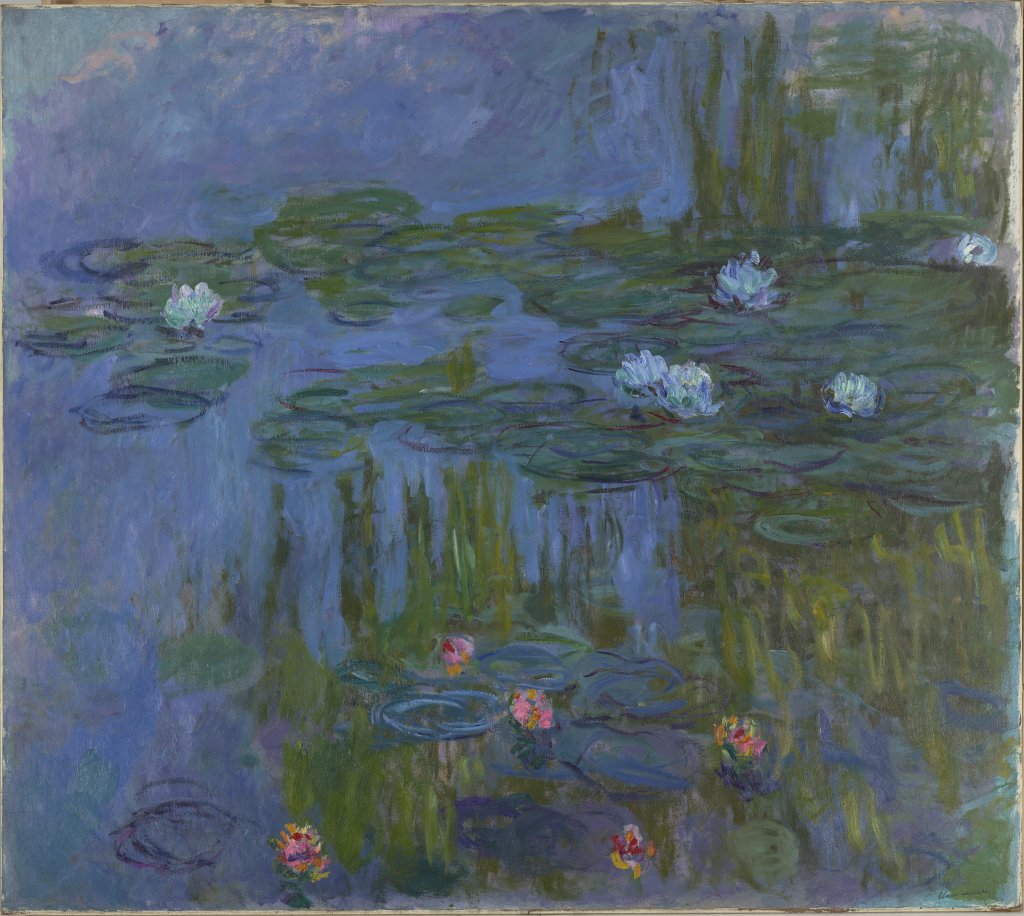

The most recent idea that appeared to me, so insistently that I felt compelled to write it down, was of painting as a scaffold. This was related to an older idea of mine, of painting as a veil, which itself was formed through reflection on a correspondence I sensed between the work of Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, and the late paintings of Monet, where the surface holds back but also suggests and contains a totality beyond the image plane. What swirls beneath the weave of marks, animating otherwise mute and meaningless gestures, is the mimetic faculty, that capacity for imitation to which Rousseau attributed our freedom. A painting’s ability to arrest a viewer’s attention depends on it provoking a dim recognition of something experienced. Reality reappears but removed at a distance, having undergone a process of transformation in its translation as art, broken apart and re-formed. Roberto Calasso, in his reconstruction of the ancient Greek mythos, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, explains that its repetitive form, with multiple versions tessellating out into dense structures of meaning and layered significance, was an attempt to portray the power of metamorphosis and consecrate its divinity. Zeus swallows the world before spitting it out in his image; before him, in the very beginning, Time and Necessity were snakes coiled and coiling together until they brought forth Appearance. Art follows much the same process, but with the difference that, consigned to a material realm in which it is physically powerless, it must make do with the image. Painting is born from contemplation turned in on itself, visions gazing at visions. The world appears on its navel. The root of man is man himself.

Claude Monet, Nymphéas, 1914-15. Oil on canvas, 63 1/4 x 71 1/8 in. Portland Art Museum.