A Farewell to Carmen Herrera

Carmen Herrera at work in Havana in 1941. Photograph: Jesse Loewenthal

I awoke the morning of February 12th to the news that Carmen Herrera had passed away at the age of 106. When I first encountered her works during their recent "rediscovery," her characteristic abstraction beguiled me. Sharp and ascetic, they inspired both admiration and rebellion. They were the proclaimed heritage of an abstract art towards which I had always felt ambivalence, and yet, they did not harbor the disdain for pictorial illusion and the pleasures of seeing for which geometric abstraction was at that time being praised. The more I looked at the paintings, the more they challenged and transformed my mode of seeing and offered new vistas into the history of art.

A collection of 15 large-compositions often referred to by the title Blanco y Verde, executed by Herrera over the course of the 1960s, have come to be seen as her most ambitious works and the prime example of her peculiar style of minimal geometric shapes and eloquent arrangements. The paintings are large and luminous, with triangular shards of bright green extending from the edges to the center of uniform white canvases. Some of them, arranged by means of a horizontal movement, recall our impressions of a landscape. They guide our eyes from their broad colored areas at the sides, seemingly nearest to us, towards an inscrutable moment at the center, a delicate suggestion of touch and contact that appears to happen at a great distance almost invisible to our sight. Others, vertical rather than horizontal, mimic the standing postures of figures in space. Whether pointing upwards or downwards, the triangles in these compositions suggest a sensation of solidity — the feeling of an upright, frontal being firmly positioned in the plane as well as in the imagined space of the canvas.

All of Herrera’s Blanco y Verde pictures are interconnected by this emphasis on vertical and horizontal movements, by a playful and suggestive relationship between figure and ground, and by the bright uniformity of their contrasting colors. But for a viewer new to these paintings, Herrera’s use of color and shape might seem merely the product of a school, “hard edge abstraction,” whose style and intentionality the artist adopts, perhaps with little variation.

In fact, Herrera’s paintings have appealed to recent critics and curators as either expressions of her identity — and thus related to the legacy of South American abstraction — or as Minimalist constructions engaged in dissolving the relation between visual elements inside the image in favor of “pushing the pictorial act” beyond the canvas. In both cases, Herrera is seen as a precursor to Minimalism, with its taste for physical, architectural presence rather than the visual experience of the artwork, and its distaste for pictorial illusion and composition as opposed to more immediate, and allegedly more social, forms of experience.

Exactly the opposite is the relationship between Herrera’s vision of painting and aesthetic experience. A horizontal canvas by Herrera is closer in conception to some of Cézanne’s Mont-Sainte Victoire (1902-1904) pictures, with their tension between imitation and geometry, than they are to Lygia Clark’s surfaces or Stella’s Black and White paintings. In a 1960 Blanco y Verde design, a green right triangle cuts vertically across the center of a white field. At the side, an identical shape goes in the opposite direction, pressed to the left border of the canvas. Our habits of looking at pictures are here very quickly activated, such as the perception of full-length portraits, for instance, which, like in Monet’s Woman in a Green Dress (1866) or in a British Grand Manner painting, create the illusion of a window-like vision wherein figures are staged at the center, often in a triangular form and clearly differentiated from their surroundings.

We are thus at first almost unconsciously tempted to perceive the green areas of colors in her painting as a solid, close-by figure standing over an unmodulated white backdrop. The triangle at the right even appears as an ironic take on this tradition’s habit of placing at the side, cut in half by the edge, a column of classical architecture, or a tree in a landscape that extends beyond the frame of the canvas, giving us the sensation of a larger world and the certainty that the painter and model were there, capturing in the same room this moment of the picture. But from the resemblance of this composition with another painting by Herrera from earlier that year, Cobalto y Blanco (1960) and a later sketch for a sculpture, it is evident that the opposite might also be the case. What appears at first as empty surroundings can also be perceived as a concrete, irregular figure composed of two frontal facing rectangles, one somewhat clumsily leaning against the other. The green triangles at the center and the side are indeed as much foreground as they are background, standing for an upright figure as much as for the empty and darkened presence of depth.

To be clear, I don’t think that Herrera had in mind Cézanne or Monet’s pictures, or any particular painting, for that matter, when she decided on the composition of Blanco y Verde. Rather, what I am trying to suggest is that the experience of Herrera’s paintings, the way the pictures ask us to see them, is different from that of later abstraction, in that they bring into play a number of our habits of seeing — habits that we often encounter in our everyday lives, but that are also preserved in the history of modern pictures. The space of Herrera’s paintings is not the real space we “inhabit” in the gallery or otherwise, but rather the illusory world of images and vision. Hers is the dream ground which, for over hundreds of years, artists have used to tell us stories, to perpetuate the likeness of people and landscapes, or reflect their feelings and visions materialized in objects. It is also, of course, an idealization of that ground and those figures — their transmutation into minimal shapes and colors in an attempt to preserve in extremis their metaphorical values and poetic allusiveness.

Paul Cézanne, Mont-Saint Victoire, 1902-1904

Thomas Gainsborough, Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott, 1778

Herrera’s early paintings in fact show a continuity with the concerns of modern painting and its interest in the artistic value of human intuition and everyday experience, portraying common subjects — still life, portraits, landscapes — from the viewpoint of a modern individual free to enjoy and meditate through them on their own moods and subjectivity. In her earliest available piece, Piña (1936), the choice of a simple, everyday subject matter serves as a springboard for the searching eye, a spirit of observation that delights in each outline and area of light and shadow and seeks to reconfigure them into a design of resonant curves and colors. Painted a decade later, City (1948) is reminiscent of pointed high-rises and towers traced by simple triangles and squares over a landscape of nocturnal light. The blue squares and yellow triangles at the right, cut by the frame, suggest that what we are seeing is not the defined and complete window to nature of older painting, but rather a fragment of our visual field, the vantage point of an accidental observer, a passerby, that has glanced casually at this scene with a heightened sensibility and made geometry of it in the imagination.

These twofold aspects of experience — the illusion of the accidental glance of a modern passerby and the imaginative transfiguration of this vision in the artist’s mind — quickly became essential motifs in the development of Herrera's works. In a series of tondos and small-scale canvases painted in the late 1940s, these shapes would become increasingly defined and tempered by a new economy of form and color that gave her work an air of closeness and stability. These paintings for once preserve that early impression of an accidental observer, but the object seen and the nature of seeing is no longer as easily resolved. Allegorical pictures such as Vision of Saint Sebastian (1949-1956) and Iberic (1949) are meant to evoke a sentiment rather than a place, an image of the character of the tortured Saint or of the mood inspired by past and present impressions of the Spanish Peninsula. Green Garden (1950) and Untitled (1947-48), on the other hand, suggest the effect of leaves and overlapping shadows, the bright silhouettes of sunlight, perceived close-at-hand, from where the eye can no longer distinguish different textures or details. Herrera’s choice of motifs are thus expanded from the abstraction of at least apparently real places, to memories and impressions, stories, and even whole societies reshaped as a unity by the mind’s eye. And yet all these themes still present to us the contemplative sight of a modern vision, unconcerned with the display of Gods, mythology, and worship, but rather interested in portraying the fleeting experiences of a city and the personal impressions of nature, the painter’s own thoughts, her travels and readings — that is, the objects that surround her everyday experience.

Comparing one of these pictures to Blanco y Verde, we perceive in both that memory of the outside world: the imaginative viewpoint of the picture and its reconstructed life that from inside pretends to challenge our habits of experience. These early pictures also already contain some of Herrera’s vocabulary of abstract design. The closed, single-color shapes are already there, derived from the motif and bounded by an elusive and indefinite background. They are rearranged also through horizontal and vertical lines, a grid that both balances and overflows the surface; and even the impression of the two bright colors in the later canvas recalls its somewhat more elaborate contrast in this earlier composition. These simple figures, these apparently random forms, are in both transfigured by that quality of a glance, by that illusion of our accidental normal looking that thrusts them back into nature and gives us a conviction of their uneasy reality.

The sheer diversity of shapes and scales in these paintings do not correspond, on the other hand, to an obvious act of seeing, but are rather crafted from materials whose relationship with what they depict is more and more tenuous. This non-identity of pictorial language and its object is maintained in tension: the charm of each of them, as Proust would say of an impressionist painting, is that we are able to discern in their trembling forms and irregular shapes a sort of metamorphosis of the objects represented.

Painted during a sojourn to Havana in the winter of 1950–1951, Untitled (Habana Series) and Éléments clairs represent the artist’s last return to a naturalistic motif and painterly style as the fertile ground for her work. These paintings were followed, upon her return to France, by Black and White (1952) and Untitled (1952), Herrera’s first geometric abstractions and the ones taken on today as the closest to the aesthetics of Minimalism. In Éléments clairs, triangles and squares are achieved in accordance with the accidents of mountains and plateaus; the orange and purple tones delineate the slopes, separate ground and sky; the greens insinuate pastures and the limits of the soil. But colors are not here applied so as to suggest the reality of the landscape, but rather irregularly sink as marks into the canvas and recall the process of coloring in. The lines go beyond any closed shape, spiral and scribble on their own, making the landscape seem merely an accident of their uncontrolled wanderings on the surface. In Untitled, a more chaotic vision dissolves the motif into patterns of color and brush marks. A freestyle automatism is countered very faintly by repetitive strokes and shapes that balance a sense of abandonment with close attention and reflection. In this struggle between feeling and theme, the landscape is transformed into a sentiment, and the sentiment into a landscape: a swirl of fantasia and chaos, the restrained but gloomy indecision of transparent squares and colors. But what these paintings ultimately present to us is Herrera’s incapacity, at the time, to reconcile her new pictorial forms with the irregularities of nature. Whereas in her earlier pictures a vision is preserved through the arrangement of the canvas, here landscape and pictorial language are irreconcilable participants of an implacable struggle. Rather than offering a fully-fleshed, if incomplete, experience, these paintings thematize its impossibility, letting our eye aimlessly wander inside the abyss between feelings and forms, mind and nature, knowns and unknowns.

That Herrera proceeded to paint Black and White and Untitled at this point in her career doesn’t originate, as an analogy with Minimalism would suggest, in a suspicion towards the value of “pictorial illusion” or “aesthetic experience,” or, to quote a recent curator, in “a systematic effort to purge her work of all but the essentials.” Rather they present her dissatisfaction with the intense irresolutions that her recent naturalistic paintings had achieved. The austere, muted qualities of Black and White and Untitled, their minimum elements, symmetry and balance, are those of a soothing draught drunk after a torment. Her last direct engagements with the motif manifested a feeling of disorientation, a confusion about what our experience of life and nature can still teach us. In her last landscapes, the world appeared as both richer but also poorer in communicative experience. The reverse sentiment of the naturalistic abundance of Herrera’s 1950s paintings is their oppressive wealth of ideas, and the accompanying illusion, materialized afterwards in her black and white works, that one can get rid of them all — that one needs to forget everything inherited from the past — and start from scratch.

Thus, of the origin of her abstraction, Herrera once said, “In this chaos that we live in, I like to put some order.” It is in this spirit of order and chaos, this desire for reason tempered by an outbound nature, that the visual execution of Herrera’s abstract works should be understood. While in the name of perfection and purity, artists like Herrera decided, to put it in Malevich’s words, “to have nothing further to do with nature,” to suspend relations with the “time-tested wellspring of life,” away from the yoke of the objective world, free from “utility,” from the service to “religion and the state,” and their subordination to a “history of manners” [1]; the life-like quality of these paintings also preserves, in its never-ending becoming, that intuitive, demonic chaos of experience.

“To me it was white, beautiful white, and then the white was shrieking for the green, and the little triangle created a force field,” said Herrera in an interview. And indeed, her playful, brilliant white not only erases what lies on its path, but brings into being a liberating energy, no longer chained to past life, but like a spontaneous creature thrusting forth the creation of a new experience. In their tension between vision and abstraction, reason and spontaneity, past and present, Herrera’s paintings hold still the sudden power of experience, our capacity to relive those lost moments of the past and unlock their potentials, not in identical ways, but under the new colors and lights of our own desires and sufferings. From what is most alive and new in her artworks, from her unique arrangement of sharp triangles and vibrant colors, arises a sudden memory; a memory of impulses, ruptures and emotions impressed upon us by a moment of the past, and which the magnetism of this identical moment in the present, our experience of her artworks, has traveled far to importune, to disturb, and raise up out of the very depths of history.

//

Piña, 1936

Iberic, 1949

Untitled, 1947-48

Green Garden, 1950

Élements clairs, 1951 Simon Dickinson

Untitled (Habana Series), 1950-51

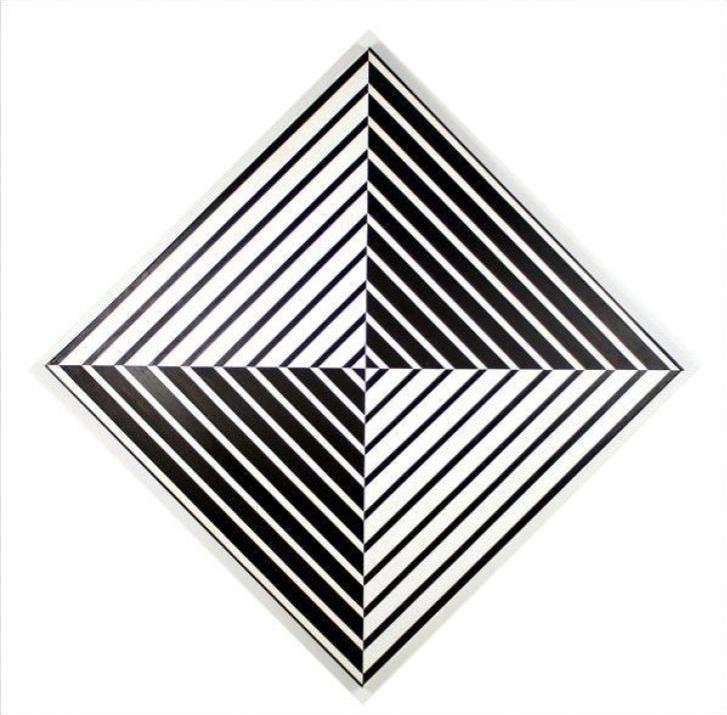

Black and White, 1952

Untitled, 1952

[1] Quoted in Donald Kuspit’s “Authoritarian Abstraction,” re-published in Redeeming Art (2004)