Review of Leave Society by Tao Lin

Leave Society

by Tao Lin

Penguin Random House, 2021, $16

Tao Lin has often been called the voice of the millennial generation. The tragedy is, that voice struggles to be anything more than the distorted echo of generations past.

With his new novel Leave Society, Lin’s self-modeled protagonist Li strikes a different tone than the protagonists of his earlier novels. Those earlier protagonists were detached and nihilistic, but in the new novel, Li has adopted an eclectic mysticism that helps him navigate the banal horrors of the 21st century with a more positive outlook. He’s concerned with organic food, natural medicine, and lost histories of early civilizations that center on cooperation and female deities.

Lin writes that “Li had been addicted to amphetamines, benzodiazepines, and other pharmaceutical drugs for three years. He’d ended the increasingly life-threatening phase by isolating himself in his apartment in Manhattan, replacing pills and friends and most of culture with cannabis and books, and finding his new interests: history, nature, psychedelics, the imagination, his parents, and his body — six things he’d previously mostly ignored.”

The New York Times review of Lin’s last novel Taipei, published in 2013, suggested that if one were to make a word cloud of the novel, it would be populated with words like stranded, disengaged, fetal, dispersed, cringing, alienated, muffled, depleted, and doomed. A similar treatment of the new novel would yield things like mystery, dream, diet, ancient, health, natural, goddess, and LSD. How do we account for this shift? Lin’s early novels chronicle the life of a 20-something in the full flower of his youth, but with Leave Society, Lin and his protagonist Li are both staring down 40. Maybe the author’s youthful nihilistic detachment has faded as age has rendered death a much more tangible thing for him, and he’s turned to spirituality in the hopes of finding meaning. But we also can’t discount the impact that the Trump presidency had on the millennial psyche. Its nihilism and apathy in part produced the conditions that allowed the Trump phenomenon to arise, and maybe the mystical turn is an attempt to atone for that nihilism.

Tao Lin, NYTimes.

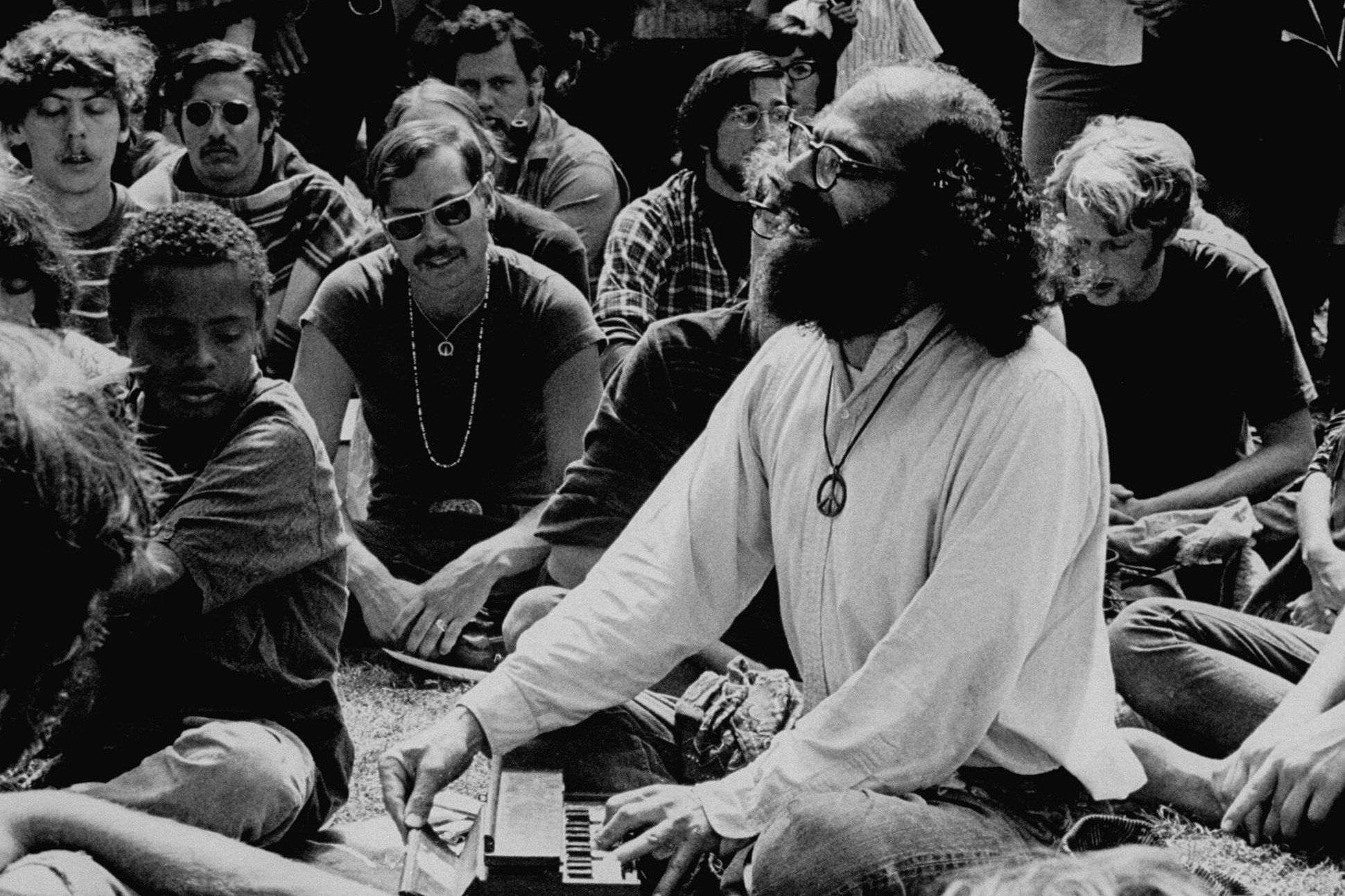

The two standpoints that Lin has employed in his work, detached nihilism and eclectic mysticism, have been hallmarks of various countercultural strands that, since the 19th century, have tried to deal with the death of God and the crisis of modernity. The mass counterculture that emerged in the 1960s in America and the West, though, provides a useful analogue to millennial hipsterism. We might see Lin as the contemporary equivalent to Beat poets like Allen Ginseberg. The Beats rejected postwar mainstream society through a cool detachment, which by the late 1960s grew into a fascination with Eastern mysticism that influenced the hippie movement and the radical politics of the time. Tragically, though, Ginsberg himself would end his career chanting about the dangers of cigarette smoke on daytime talk shows.

Though millennial counterculture, of which Lin’s novels are a chief expression, superficially resembles the styles of that earlier generation, it has been stripped of its political valence. The 1960s political upheavals, fraught as they may have been, did at least imagine that a fundamental transformation of the social order was possible. Awash in postwar affluence, the 1960s generation still felt they had been denied something essential. To be materially secure was to be spiritually bland. They felt their lives lacked some vital component that modern liberal democracy had promised and failed to deliver. With their Levi’s and Coca-Cola, they were free in their unfreedom. The millennials, on the other hand, have forgotten that modernity had ever promised them anything at all. All they know is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and the acute loneliness of being left on read when you finally get up the courage to slide into her DMs.

Allen Ginsberg, Poetry Foundation.

Nowhere in Leave Society is there a notion that 21st-century existence could be anything other than what it already is. The desire to leave society is wishful thinking. Li rejects society, but we know and he knows that escape is impossible. The best one can do is to eat organic foods, limit exposure to cell phone radiation, and bear witness to a past when humans worshiped goddesses and weren’t subject to male-centric “dominator culture.” Any thought of transforming society is of course off the table. His retreat is a personal one.

Throughout the book Li tries to manage the health of his parents and family and the health of his relationships to them. They take trips together to the mountains to soak up phytoncides and anions, “air vitamins crucial to mental and physical health.” He convinces them to remove poisonous mercury-based fillings from their teeth, and he lectures his father about using statins, a type of cholesterol-lowering drug that Li claims causes cancer, depression, amnesia, dementia, and other problems.

The dynamic between Li, his parents, and their toy poodle Dudu is warm and funny, filled with constant bickering and apologies. The emotions are simultaneously heightened and flattened by Lin’s signature dry style of prose. Neither of Li’s parents, for example, are ever given names. They are simply referred to as “Li’s dad” and “Li’s mom,” yet that doesn’t prevent them from becoming fully realized characters.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, National Geographic.

The novel ends with Li and his new girlfriend taking a vacation to Hawaii. The couple talk about leaving their stressful lives in toxin-laden Manhattan to escape permanently to Hawaii where they would sustain themselves by running an Airbnb. We’re supposed to be left with a sense of hope that Li and his partner will begin a new and happy life coasting on the app economy in their phytoncide-filled oasis, but it sounds rather dystopian to me. The unresolved project of freedom can’t simply be brushed aside. No matter how much you want to leave, society and its unfulfilled promises always have a way of finding you.