Where Are The Music Houses?

You must change your life.

- Rainer Maria Rilke

In the late 60s the visionary composer La Monte Young conjectured that people in the upcoming age might grow up in these new “dream houses” — Young’s term for his innovative longform music environment. The image is an inspiring one, with an exciting new music form propagating across the new age, a kind of church of new music, or the construction of something akin to opera houses, but rather exuding an exciting new music appropriate to our modern era. Not only would there be great expansion of musical knowledge and form, but of consciousness as a result, transforming the world listener by listener. And yet half a century later there have been no new Dream Houses. Why? After all, there’s evident need ~ not only is Young’s decaying Dream House still a destination for musicians, but we’ve seen the proliferation of sound baths and listening rooms, one-dimensional caricatures of the multidimensional Dream House artwork. We have artist chapels and museums built for paintings ~ why not sites customized for particular music art works? We once built cathedrals apparently for God … but they were really for music. What would it mean to self-consciously create grand architecture for modern music? According to Maryanne Amacher, who built fantastical (albeit temporary) ‘Sound Houses’ in the 1980s, Mondrian also fantasized about the construction of buildings dedicated to specific music and art works. Stockhausen built domes and staged music on different floors of houses for a spatialized music that was “wonderful”, and “not very expensive, I must say.” Yet it wasn’t continued. Will construction of this social-aesthetic project ever break ground?

~ Utopia ~

I suspect there are manifold reasons for the lapse of this dream — as much social as aesthetic — but I'd say the most significant one is ideological and concerns anti-utopianism. Broadly speaking, the postmodern generation reacted very negatively to any utopian imagination, a resignationism due to the association of utopia with freedom, which postmodernism rejected. One can go into the reasoning, but in my opinion it's conservative, nihilistic, and I don't see the need to give it unwarranted attention. It’s no secret Gen X were resigned slackers, and as Adam Curtis pointed out in HyperNormalisation, were content skulking the ruins of those who did once dare to change the world. This attitude — and it was an attitude more than critique — was inherited by the Millennials, whose sensibility can best be summarized as administrative and institutional as a result. Not in the least utopian, too cool, too self-righteous even for spirit and so in truth a closeted nihilism. Kinda sad, really, when one considers the Millennials were the generation to usher in the new millennium, which was once inflected with an excitement for the future. And yet Millennial artists are often more interested in reproducing 20th century aporias, less capable of imagining a new aesthetic world than being reformers of ruins. The over-long 20th century. To relate a telling anecdote, a few years ago an acquaintance was heading West to survey architecture for research, asking for recommendations. I suggested he visit Arcosanti, the "urban laboratory" in the Southwest, no less cosmically visionary in its scope than it is impressively aesthetic and art historical in its practical realization. At any rate, something to be seen to be properly judged. His response was a knee-jerk "No! Nothing with any utopianism!" Such attitudes represent the naturalization of the postmodernism utopia taboo, here from an art world impresario who is awarded tens of thousands of dollars by a major NYC art grant organization for academic projects evacuated of constructive artistic vision, let alone practical implementation of vision. I cite this only as an example of where the status quo values currently reside.

Yet while there's a reaction against utopian thinking, art itself has a utopian edge. Such utopianism does not exclusively concern such large scale construction and architectonics, but rather the expansion of human consciousness from out of its own dreams of possibility, unfurling from out of the “private world of revelation” (Amacher). Aesthetics itself was always utopian in nature —

The individual’s esthetic conscience represents ‘mankind’ potentially, but not always actually, and it is the ideas of ‘mankind’ that justify the claim of any judgment of taste to universal validity. A subjective judgment is not yet objective, but it ought to become so. Esthetics, even for the cautious Kant, is tinged with Utopia.

- Carl Dahlhaus

The greatness of Beethoven’s music was in large part due to his high hopes for human emancipation; the music didn’t merely reflect the hope for freedom and enlightenment, but seemed in some sense an attempt to augur it. Art operates in the realm of “potentially”, and so is not reducible to art-for-art’s-sake passivity — it seems to demand change. As György Lukács said, art always says “and yet…” to society, preserving the hope that life might become otherwise. Artworks like Beethoven’s are placed before our perception, ahead of us, demanding that our perception change to even experience them. Likewise, when one looks at paintings in history, ranging from Velázquez to Cubism, one imagines that viewers in their own moments didn't yet possess the perceptual apparatus adequate to experience the works. It had to be drawn out, so to speak, they had to work to gain it, aspiring towards the artwork. Consider Raphael's The Transfiguration (1520) — the mad boy's eyes are literally torn apart at the sight of the illumination. In order to experience illumination, his vision had to be "transfigured". It is an allegory for experiencing art itself. Such paintings necessitated the expansion and growth of visual experience.

Artworks know more than we do, Adorno would say, for these and other reasons. This is the true meaning of the social aspect of art, which the Millennials have grossly distorted. So too is it the significance of the spiritual in art, the historical self-realization of our aesthetic capacities. Such experience is overtly evident in music, with the ongoing emancipation of dissonance, for example. Since the middle ages, more and more harmonic intervals are able to be heard and experienced without displeasure — whereas only a few hundred years ago a paltry few intervals were considered listenable, nearly every note in our tuning today can be heard without protest from the ear. Even the most adventurous jazz music still goes down easy, and atonal music is a necessity for every Hollywood blockbuster. Composers today, led by artists like Young, may freely invent their own harmonic systems to continually expand harmonic experience. For Young, new harmonic constructions can cultivate new musical feelings. It is an art for the expansion of our emotional intelligence.

Consider too the developmental youth of music in general, at least according to the 19th-century new age philosopher Richard Maurice Bucke. In his book, Cosmic Consciousness (1901), he theorizes that musical experience only became possible in the last millennia, that our ears simply weren't developed enough to discern all the harmonies that 19th-century music so excitedly explored. He cites evolutionary science of vision as an analogy — there was a time in the deep infancy of our species where our retinas could only perceive black, then slowly we could discern red, and so on and ever on. In his Impressionism and Science essay, Meyer Schapiro quotes the poet Jules Laforgue on his defense of Impressionism on these same grounds.

Jules Laforgue declared not only that their work was scientific but also that the strange aspect of Impressionist coloring corresponded to the most advanced sensibility in the evolution of the color sense of the human species. Laforgue knew the argument of an ophthamologist, Hugo Magnus, much discussed in the 1870s and 1880s, that the color sense of mankind had evolved in historic times from an early state in which only four or five colors were discriminated, as evidenced — he supposed — in the writings of Homer.

- Meyer Schapiro

Whether or not this is objectively true is debatable, but it does show an excitement around the hope for an awakening of our aesthetic faculties to new perceptual experiences of color and tone that are difficult to articulate. It’s well-documented that painting in the 19th century was largely gray-brown until Delacroix and ultimately the Impressionist revolution. In the modern world, we need no longer rely on chance evolution for the continual expansion of our aesthetic faculties — this is (one reason) why we have created art. It's also why technology and art are so interrelated. Technology may be framed, at least in many instances, as an appendage of our aesthetic faculties. Technology doesn't make art possible, art makes technology possible. We invented photography so that we can see deep into the microstructures of our world, as well as visualize the most distant black holes. And visualizing a black hole is as much an aesthetic triumph as a scientific one. Of course, no amount of technique or technology will ever solve problems of the imagination. And it is indeed a far-reaching and vivid imagination which determines the quality and expression of artworks. Without which it truly is mere bangin’ on a can.

~ Augurs ~

In my opinion, the best artists operate in this realm of the transformation of our aesthetic faculties. When one thinks of “new music,” this is what should come to mind, though it's a far cry from the concerns of the new music industry, which is still too often about pedantic performative displays, contra Stockhausen’s values, where "the enlargement of our consciousness seems to be more needed at the present time than being able to convince people of one's genius as a fantastic performer or composer of music in an established style." John Cage’s The Future of Music: Credo authorized the new music, stating that “It is now possible for composers to make music directly, without the assistance of intermediate performers.” But now it’s all performative, isn’t it? And by so many musicians’ own admissions, decidedly not intellectual. Anti-thinking, as if we’re still old romantics conjuring some vague divinity. A thousand times No! Perhaps even ashamed to be associated with thought or ideas. It's quite a mass deception to prop up ambient new age music in a culture that mocks the very idea of a new age, and rails against the very idea of enlightenment. Hence the irony which became so tiresome. (Perhaps it’s even a psychological addiction to failure that makes it appealing to begin with?) Electronic music, a form almost completely synonymous with Stockhausian utopianism and the expansion of consciousness… Does it aspire to more than fiddling with retro synths just because it performs the image of the mad genius? But where's the transfigurative madness, and is it really genius? Stockhausen revived the Ancient Greek character of the augur, but to what end?

The artist has long been regarded as an individual who reflected the spirit of his time. I think there have always been different kinds of artists: those who were mainly mirrors of their time, and then a very few who had a visionary power, whom the Greeks called augurs: those who were able to announce the next stage in the development of mankind, really listen into the future, and prepare the people for what was to come.

- Stockhausen

In the modern world where artistic production is democratized into kulture, most artists will be mirrors mirroring each other. The 21st century mirror-soul. There are few visionaries who lay before us a revelatory art — an art that reveals possibilities — that demands we change ourselves to experience it, that cultivates “enhanced sensory endowments”, as Amacher described Stockhausen’s values. Where are the Amachers, who activated the dormant potentials of our listening faculty, kindling imaginative possibility in the process, who fantasized about what unthinkable music-perceptual experiences we might be capable of in millennia to come, who thought of music not as a performative craft or personal expression, but rather as a form of revelation, very often via site-specific sound houses and music rooms, a "new genre for experiencing sound", conceived "TO MAGNIFY THE EXPRESSIVE DIMENSIONS OF THE MUSIC"?

The idea is to create a world for the audience to enter, where sound shapes appear to be much larger than life, or so small they may be touched in front of one's eyes, heard as though many miles away, or felt inside the listener.

- Amacher

Such thinking requires an abstract consciousness, which is why Amacher was so concerned with virtuality. Amacher wrote a series of pieces in the 70s titled Long Distance Music, which critiqued the narrow scopes of listening “confining us to the boundaries of ONE PLACE situations ALL THE TIME,” and asked if music could rather be experienced “a 3rd way”, at greater distances. It is in many ways the opposite of site-specificity, aiming to break down situational barriers and openly exploring virtuality. It is specifically this holographic character of Amacher’s music that is so beautiful and compelling to us. Of note compositionally, Amacher later pursued tuning for second-order beating, which is not the overtly direct ‘first-order’ beating that we can easily discern acoustically when two waveforms are slightly detuned, but a more distant and abstract perceptual form. It demands aesthetic distance and the liberating aspects of aesthetic alienation. Stockhausen’s “as if” —

We now have the means technically to make the sound appear as if it were far away: ‘as if’, they say. A sound that is coming from far away is broken up and reflected by the leaves of the trees, by the walls and other surfaces, and reaches my ear only indirectly.

- Stockhausen

This kind of distance and “indirectness” can also be profoundly more expressive and multidimensional. It made for more figurative layering and shading, perhaps not unlike Leonardo’s sfumato technique that excelled at representing nature, especially those distant, dreamy skies. This distance and indirectness is what Baudelaire loved so much about Wagner’s Tannhäuser, which led to Impressionism, and was later developed in Schoenberg’s construction of klangfarbenmelodie (tone-color-melody), which was a basis for Young’s drone music, Ligeti’s micropolyphony e.g. Lontano ~ which literally translates to “distant” ~ Spectralism, still informs contemporary composers like Georg Friedrich Haas exploring a more diffused sound (self-consciously or not), and is what ambient musicians strive for but are incapable of doing very well. Baudelaire captures the feeling …

I felt myself released from the bonds of gravity, and I rediscovered in memory that extraordinary thrill of pleasure which dwells in high places. Next I found myself imagining the delicious state of a man in the grip of profound reverie, in an absolute solitude, a solitude with an immense horizon and a wide diffusion of light; an immensity with no other decor but itself. Soon I experienced the sensation of brightness more vivid, and intensity of light growing so swiftly that not all the nuances provided by the dictionary would be sufficient to express this ever-renewing increase of incandescence and heat. Then I came to the full conception of the idea of a soul moving about in a luminous medium, of an ecstacy composed of knowledge and joy, hovering high above the natural world.

- Baudelaire

~ The Listener’s Music ~

I think the indirectness is in many ways about evocation and the art of suggestion. It is the presence of a compelling, but as yet inarticulate form that excites the imagination and which the listener must actively interpret and strive towards to articulate with their own aesthetic intellect. Auditory science reveals that our listening faculty itself projects tonality, subjectively creating what is usually presumed to be something objective. The naturalness of “sound” is actually actively created by our aesthetic faculties, but we don’t recognize this. Such an intellect needs to be felt out, so to speak, and developed. It’s related to what Amacher called “the listener’s music”. Music as a form of suggestion for the listener, which is perhaps why music is so associated with dream, from Young’s Dream House all the way back to Apollo. Likewise, Kafka has a passage in The Castle that describes this distant dreamy music —

It was as though the humming of countless childlike voices —but it wasn’t humming either, it was singing, the singing of the most distant, of the most utterly distant, voices — as though a single, high-pitched yet strong voice had emerged out of this humming in some quite impossible way and now drummed against one’s ears as if demanding to penetrate more deeply into something other than one’s wretched hearing.

- Kafka

Music is not merely about “hearing” in the way experimental music has fetishized for the last half-century ~ it is rather an expression of searching for something accessed by, but beyond listening, something deeper, more distant and unknown within us. Indeed, our hearing in its current state hardly deserves affirmation. When we say listening, what we really mean is a kind of thinking. What are we really after in trying to “penetrate more deeply into something other than one’s wretched hearing”? It’s hard to say, but it seems related to the utopian edge of music that implies a ‘going somewhere’, some telos. What Adorno liked most about Beethoven was his ability to freely invent figures, dissolve them, and then invent new ones, seemingly ad infinitum. A kind of restless attempt to uncover or unfurl tonality and so very literally an art of revealing. Music like this is colloquially referred to as “driving”. One of the characteristics of modern tonality is the ability to leave things behind — it’s not simply creating new figures, but also an art of letting go of the past. In voice leading, there is considerable attention given to how to leave previous tones behind in an aesthetically truthful way, not merely make new things. I think the resulting suspended feel of modern music ~ Schoenberg likened tonality to a gas ~ is very compelling to people in our era who are in some senses cultural barbarians who cannot let go, but who are also moderns making everything solid melt into air. In early aesthetics such as Herder’s, music itself was considered an energetic art. But energy in what sense? I think the energy is directed towards a modern kind of uncovering, a critical-artistic drive to get to the bottom of things, and art’s inevitable relationship to enlightenment in our era (even when it’s a negative relationship). As Clement Greenberg stated —

It was no accident, therefore, that the birth of the avant-garde coincided chronologically — and geographically, too — with the first bold development of scientific revolutionary thought in Europe.

Amacher’s “energy of recognition” is an expression of art’s tricky relationship to knowledge, as mediated by appearances. This drive towards revelation is also why such artists are inherently critical, and is the true meaning of the critical artist.

Yet this “listener’s music” that tries to uncover something latent, or perhaps dormant, is in sharp contrast to the Millennial values of direct, ritualist performance (even where it’s not literally performance, but performative painting etc.) — music more for musician’s hands than the intelligence of the reflective ear. Everyone’s free to have their own values, and there’s room for all kinds of art, but it’s a value that likely won’t be shared by those few artists seeking a listener’s music that might expand our aesthetic consciousness. As Hegel noted two centuries ago, the days of the cultic, ritualist character of art are long gone. And good riddance, free at last! Will artists today decide to be as modern as consciousness already is, and learn the art of suggestion, or will they romanticize an ancient past where art served religious function, even as art rituals today — transposed from religion to political ideology — fail to connect with listeners and viewers? In other words, will artists take up the task of art, even and especially if this means constructing and expanding our perceptual capabilities from scratch, from an infant-like state? And will music in particular finally be considered an art, presented in a manner more conducive to aesthetic reflection instead of entertaining, ritual performance, an experience we’ve carefully developed in the visual arts and literature, and which our young music might learn from? It’s interesting that Baudelaire wasn’t just in a romantic swoon over the sublimity of Tannhäuser, but also that he thought it’s meaning was a synthesis of reflection and joy ~ “an ecstacy composed of knowledge and joy”. This is Amacher’s “energy of recognition”, and also very much exemplifying Nietzsche’s ideal of a “Singing Socrates”, a synthesis of knowledge and joy, a “Gay Science”. There was a reason why Amacher and Catherine Christer Hennix preferred to present their work in museums or art installation contexts rather than concert halls or music venues, and why Stockhausen and Young felt the need to construct their own structures conducive to their musical art. With electronic music reproduction, musicians are now free for the first time in history to overcome the hitherto transitory limitations of the musical medium, and make lasting art objects of their music. But why have so few music artists taken up the task?

~ Evoking Potentials ~

The otoacoustic emission form that Amacher explored is also, curiously, implemented in clinical practice by audiologists to discern if infants are able to hear properly ~ they’re called ‘evoked potentials’ ~ ie a form operating within the infantile state of our current perceptual capabilities. The realm of potential. If music is an art form of “energy”, consider that energy is very much about potential. The form itself — a kind of virtual aurality — is a means by which listeners can re-feel the infant state of their listening aesthetic faculty, which can in turn inflame the imagination for other possibilities and forms. When listening to one of my music house environments, one listener reported recovering a memory of her teeth coming in as a child. By analogy, after looking at good paintings, nature may appear more vibrant, more chromatically exciting, we may regard it differently because of the way painting teaches us how to look. Art doesn’t just reflect or express nature, it changes how we experience nature and the meaning of nature itself. Art in this sensibility can endow us with a hyperacute sensitivity. What might it mean to feel childlike, with all the excitement of possibility of discovery, exploring the frontiers of an unexplored world that comes along with childhood? Evoking potentials, indeed.

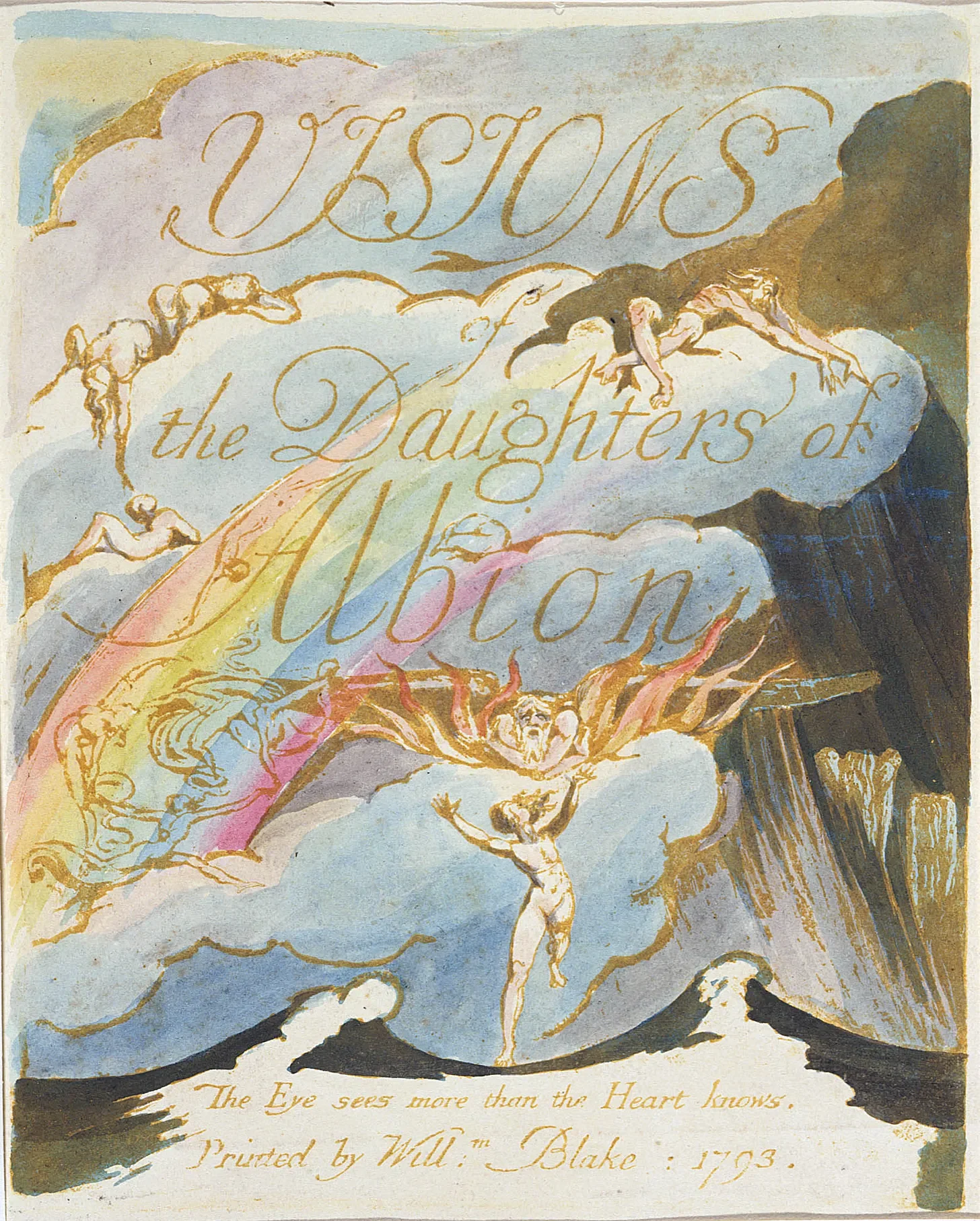

Where are the new Dream Houses, exploring nascent harmonic experiences and auguring new feelings transmitted with an uncanny acoustic resplendence never before heard? Do our artists want to feel anything new, or would they rather be performative actors, LARPing as artists, mirroring each other’s high-class propaganda? Will our fashion-grey musicians continue to hunch over their musty old organs, skulking in the basement of music history, bony old skeletons rattling desiccated songs of impossibility, looking morbidly backwards where visionary artists might look outward? What would that outward growth feel like and consist of? Whither our psybertonal glowup?! Where are the new dream houses — literal and proverbial? Will artists in the 21st century make an art of the energy of recognition, or do they simply want to express themselves therapeutically? Whither the new age and who will augur it? Like Young, will they be "American Mystics" in a spiritual-aesthetic tradition going back to Whitman? “Let those who sleep be waked!” (Whitman). Will our solemnly serious artists grow capable of joy, and will they seek knowledge rather than political ideology? Or will contemporary nihilism be made right, ever-prone to its self-righteous resignation regarding the possibility to change ourselves and transform the world? Will 21st century artists declare self-defeat, or continue the modern revolution in aesthetic experience, pursuing freedom and excellence? When it comes down to it, what is so compelling about artists like Stockhausen, Amacher, and Young is the enthusiasm for a freer aesthetic world, an enthusiasm for a revolution in music consciousness which stands out amidst a culture that is generally jaded, and even aestheticizes its jadedness. “Shatter, shatter the law-tables of the never-joyful!” (Nietzsche). Where are the Daughters of Albion, and what are their visions? Will they awaken and freely explore the erotic potentials of human music ~ eccitato! ~ or will they be professional musicians of a chaste “adult contemporary”? ~ Or ~ will such visionaries simply be exiled or ignored in the kind of society we live in? Perhaps our society is too cynical to support anything of such ambition today, too administrative, too mean, too scornful! Or worse, perhaps artists themselves today desire nothing more than to be the awarded lapdogs of an official state kulture?

I leave off with Rainer Maria Rilke's Archaic Torso of Apollo. Transcending mere art appreciation, Rilke felt nothing less than the need to change his life while reflecting on the ancient image of Apollo. Here's to the defiant 21st century artists who might also dream of changing their lives, who desire freedom to change.

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

//

Maryanne Amacher’s Sound House (1985) at Capp Street Project, San Francisco.

Courtesy of the Capp Street Project Archive, CCA, San Francisco

Raphael, The Transfiguration. (1516-20)

William Blake, Visions of The Daughters of Albion (1793)

{ AN IMAGE OF A MUSIC HOUSE SHOULD BE HERE BUT THERE ARE NONE TO SHOW }