Groundwork for a Study of Maryanne Amacher

An Introduction from the Editor

To speak of composers at this late date is often met with suspicion, and perhaps rightfully so, for how does the great mass of past music confront the listener but as bits of scrap metal, a thrice-repurposed sofa, a floor-to-ceiling print of Pierre August Cot’s The Storm in grandma’s bedroom? But when the cry of such a maniacal conscience as that which we call composer resonates through history with a young imagination, strange and mysterious processes are set in motion which theory could hardly prescribe in advance. Bret Schneider’s Groundwork for a Study of Maryanne Amacher is a great tilling of the field, unearthing lost treasures and making fertile once again land which may bear unlikely musical fruits. It is a tocsin for young composers and musicians to stake their lives on as-yet unrealized possibility. It is a challenge to the music critic to work through the musical tradition and experiments he has inherited and to go over once again what they have forgotten about themselves. It is a bet that Mozart’s musing, that we have yet to discover what music is really capable of, may still be true. We hope this will be the first in a series of deep engagements with composers and their legacies in the pages of Caesura.

—Erin Hagood

Genius of the heart: as it is possessed by that great Hidden One, the Tempter-God and born Rat-Catcher of the Conscience, whose voice can climb into the underworld of any psyche, who never speaks a word or looks a look in which there is not some hind-sight, some complexity of allure, whose craftsmanship includes knowing how to be an illusion — not an illusion of what he is, but of what constitutes one more compulsion upon his followers to follow him ever more intimately and thoroughly — genius of the heart which renders dumb all that is loud and complaisant, teaching it how to listen, which smooths rough souls and creates a taste in them for a new desire: to lie still like a mirror so that the deep sky might be reflected in them — genius of the heart which teaches the bungling and precipitous hand to hesitate and handle things delicately, which guesses the hidden and forgotten treasure, the drop of goodness and sweet intelligence beneath layers of murky, thick ice; which is a divining rod for every speck of gold that lies buried in its dungeon of deep muck and sand — genius of the heart, upon whose touch everyone departs richer, not full of grace, not surprised, not enriched and oppressed as though by strange goods, but richer in himself, newer than before, cracked wide open, blown upon and drawn out by a spring wind , more uncertain now perhaps, more delicate, fragile, and broken, but full of hopes that have no names as yet, full of new will and flow, full of new ill will and counterflow

— Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

The geniuses of the heart who compel their contemporaries to courageously pursue distant possibilities previously invisible are increasingly rare. It is something of this social spirit that one perceives in the character of Maryanne Amacher, the singular sonic utopian laboring away manufacturing aural evocations, a prismatic evocation herself, the diviner who would foster a culture of sensitive listeners and a new “listening mind” by mining gold deep in the waxen biology of inner ears, composer of aural characters far away from reality as we know it, who left every listener broken open and exposed to aesthetic uncertainty. Just over a decade after her death, one sees how her ear-dancing chaos inspired those around her to foster her fledgling star, for example in the tight coterie who have assembled the Maryanne Amacher Foundation, which is curating her long-secret archive (soon to be available at the New York Public Library), staging performances (e.g., “Petra”), and publishing selected writings. Amacher’s hermetic art is in the process of being exposed for the first time, so that her dispersed adepts are relieved from needlessly scavenging for snippets of cryptic texts buried on obscure websites or out-of-print zines from the 80s. Now is the moment of Amacher’s rebirth.

//

Maryanne Amacher at the grave of Ludwig van Beethoven. Photographer unknown.

Naive Discovery

In general, the salvage and historical revising of obscure electronic musicians from the mid-20th century is now an academic tedium: the “rediscovery” of those artful souls who have been — one only hopes meaningfully — dredged from the dustbin of history, and who are often almost just as quickly put back into said dustbin after a compulsory dusting off, and often one scents shrewd careerism in the dust plumes, possibly exposing new allergies. The brief, pseudo-populist exposure of electronic composers often adds up to very little in substance, and it poses the question of what could give substance to what is substantial only in the theoretical, private lives of those few adept curators. But the case of Maryanne Amacher suggests distinct possibilities: her work is a rare instance of galvanization, of many listeners actually being inspired in an unusually stimulating way, and her Selected Writings is framed as exemplary of an especially historically-conscious generation of artists. Amacher is also exemplary of the contradicting values and commitments, knowledge and deskilling, socialization and individualism, power and sensitivity we expect from artists in our era. When a friend played her Sound Characters for my young ears in 2001, I immediately felt that I had to know what this was, how it was that my listening ears were creative ears, vibrating in a way I had no referential experience for. Who discovered such a powerful “neurophonic” affect and why was she the only one doing it? Or was it a rediscovery? And if so, then does that entail a revaluation of the value of discovery, or a different theoretical understanding of recovery? Within a split-second a new paradigm of music, mode of listening, and imagination of possibilities opened up. Abstract imagination about transformation and new experiential capacities were excited no less than my body. Amacher inspired me to question reality and pursue an otherworldly “sonic art” as fully as possible, a commitment she articulated well in her own “Letter to Parents” as a young composer: a radically naive statement of intent about her unwavering commitment to music. In Amacher’s committed character flickered the appearance of an absorbed art. It had as much to do with the sound itself as it did with the compelling image of someone meaningfully absorbed in real activity. After waiting four years to catch a rare one-off performance at Roulette in 2005, my commitment was confirmed: her performance exceeded already unusually high expectations. The rare image of an artist who gives more upon each deeper reflection or experience with their work. How could one be surprised at this — her aesthetic philosophy openly emphasized its performance in expanded acoustic space that delimited the listener’s capacity to consciously reflect upon, and so change, the music being performed. Amacher’s “exciting” “ear tones,” her music of the “third ear” — a term lifted from Nietzsche’s aphorism about the capacity for reading, listening, and interpretive expression in Beyond Good and Evil — had a compounding effect when played in a room full of people; one could almost see, and very palpably feel, the sounds pouring out of their own and their neighbor’s ears, in turn affecting what they heard and how their own ears “emitted” vibrations. With one formal innovation, she appeared to transcend all the aporias around the performer-audience stasis in our era without directly addressing such tiresome concerns. The audience’s sense of aesthetic camaraderie — in the best sense of people who are independent but together — was inherently “social” without needing to call attention to the social aspect in a pedantic or ascetic way. This social aspect was catalyzed by a voluptuous musical content which successfully gripped its audience, who were connected by a rare emotion of wonder and excitement, what she identified as an “energy of recognition,” whose only justification was its audacity in exposing habits and a libidinal pleasure in negation. For in Amacher, the idea was posed that only by underscoring the deeply individual listening experience, of submerging deep into one’s personal perceptions, and exposing ways of listening to tabooed musical experiences (e.g., extreme decibel levels and pitch registers), could a truly social art and “new music” emerge.

As sound characters — a concept she devised that seemed to suggest a type of figurative forming of sound, and which she long considered almost literally as characters put in tension as if in an opera — Amacher would have lived with her sonic figures, spent time observing and developing their peculiarities. This personal, psychological relationship with “sound characters” challenges the tendency to consider “sound” as a given ambient phenomenon autonomous from human activity and expression. The power of her music was also due to her composing intuition, as she transitioned and mixed the different sound characters. For instance, the “drone” character in the performance, (for lack of better terminology) was unlike anything that we would call drone today because it too expressed an exciting affect, the inimitable stratification of its tonality “seemed to contain energy in all frequency ranges at once, yet never approached white noise” (233). In the short span of 20 years, this value of excitement has been jaded over by various tendencies to legitimate art’s very existence, which imprints upon much new music a melancholic character — values of profundity, self-importance, completeness, and solemnity eclipse the once exciting character of possibility that pointed to something far beyond itself, because it was far inside itself. And this oscillation of pulling-in and pushing-out, which has its poetic image in the loudspeaker’s motions itself, is not about either of those things themselves, but in the rapid oscillation of their extremes evokes different figures that are as alien and incomprehensible as they are tangible.

//

Energy of Recognition

In Amacher’s “Don’t be alarmed!”, and its attendant education of perceptual phenomena, the listener could trust in a sound scientist as they pilgrimaged to the upper registers of pitch and frontiers of listening self-consciousness. Her practice and the type of listening sensitivity it cultivated relied upon a value system of the artist-as-knowledge-producer, but in a post-enlightenment era. Her utopian art, her status as a pioneer, openly contradicted the anti-enlightenment and anti-utopian ideology of her era (and which persists). The Selected Writings frames Amacher as a “composer-theorist” who “approaches new knowledges” with a “ferocious autodidactic sensibility,” and she herself intended to evade the “idiot composers who can’t write about their work.” Amacher is an exemplary “research-based” artist, though in a way that the editors distinguish from more institutionalized research by her informal, public intellectual “home research-based practice” (15). Throughout her writings is repeated the practical thesis that acute consciousness of latent classical music dynamics is transformational. The stakes of her art was the creation of a “new music, in the sense that the listener now has the opportunity to REALLY CONSCIOUSLY ‘feel’ what is happening to his body via the music, and more importantly, begins to experience the ENERGY OF RECOGNIZING the tones being created in his ear and brain, in response to the tones sounding in the air… it is a new energy, releasing what has been suppressed by subliminal perceptions.” It is a new energy by virtue of it liberating something old. Discovery is never new, it is about dredging up something existent and buried for new needs.

//

Scientist of Intuition

Amacher was no actual scientist. Her practice was deeply intuitional and lacked the rationalization or methodologies usually associated with such a mastery of material. Her artistic, composerly intuition is not only a redeeming quality for her, but is potentially a redemption of the forgotten and misunderstood philosophical concept of intuition, or perhaps experiential knowledge itself, which aesthetic philosophy has long proposed as a powerful means of knowledge. Amacher is a scientist to the extent that so many scientific discoveries came to the discoverer in dream, reverie, imagination, or kinaesthetics: i.e., not through “science” at all. In an interview with New Music Box, Amacher is characteristically elusive on the “how” of her ear tone innovations, which is really what people wanted to know, despite the psychoacoustics books and scientific studies she references. Knowledge of listening was what stimulated much interest in her work, but it was also, acutely, knowledge that was denied, at least in its own historical moment. She constantly reiterates the point that humans don’t yet know what they’re doing with music, that there is a world of musical experience buried beneath the surface of music that her profound efforts have only barely touched upon, and that no one else seems to even be aware of, much less interested in. Underlying any hopes for musical transformation is a universal claim — that such transformation is dependent on, and will benefit all humans. A culture of discovery is put forth, but the practice of discovery in our era is more implied or simply referenced than it is illuminated. How, then, could one be able to impart a knowledge that is unknown to all? It is evident that she could only impart her knowledge of not knowing, though in a very specific way. The tendency to hear some kind of wizardly mastery in the ear tones — which is doubtlessly present — also occludes the transitional aspect and the way they pointed to other possibilities. The ear tone work seems to say, “Do you now hear what is possible? Even if this specific sound is undesirable, it points to other possibilities of experience.” Ultimately, Amacher clarified that she worked in a personal, sensual, experiential way, feeling out what resonated and freely experimenting within a dynamic feedback system of “observing,” listening and tweaking at home in her studio. Such a self-critical listening practice, and not the overwrought methodologies tacitly associated by “scientific” art, was simply necessary for innovation but, more to the point, emphasized the individual as a possible revelation. And the concept of a feedback loop in the making of this music seemed to appropriately echo, or serve as metaphor of the nonlinear feedback distortion of the ear tones. Such a feedback in creation resembles what Nietzsche called “philosophizing with a hammer” — by “hammer” he actually meant a tuning fork. The Additional Tones Workbooks display a mind in a personal research mode, where she tests out the psychoacoustic hypotheses of Roederer et al., taking notes on her own perceptions and capacities for listening. Recording her own revelations in the workbooks and also her self-psychoanalysis of musical preferences indicates that the excitement of discovery or energy of recognition is more like an energy of recovery. It also shows a valuation of the vicissitudes of individual capacity for experience over objective or metaphysical values of “sound.” Amacher’s art is exactly the opposite of a pacifying, self-therapeutic body culture: it is a demystifying art of intensification and difficult self-awakening. For instance, in her interview with Jeffrey Bartone, she says: “In fact, my interest in any such piece as this, working with the environment, has never really been for the sounds. I’ve never been interested in boat horns or water waves or birds. My main interest in doing this has always to do with the ways of hearing, and us and our responses” (213).

//

1001 Years of Dissonance

Efforts to subordinate Amacher’s work to relevant social issues of our day (as some kind of, e.g., easy listening or sisterly drone) is to ignore her dissonance, to disregard her far-out, expansive interests, and not fully experience the extreme-decibel lightning storm of her music characters, one of which she named ‘God’s Big Noise,” and all of which seemed to be conjured from a tabooed realm. The extreme amplitudes, especially when channeled through structures, render an image of music trying to break through and out of itself, as if some alien and subcutaneous element is pushing it outward. The extreme expansiveness of this outward-directed music has an analog in the expansiveness of futuristic projections of possibilities for new ways of hearing. But this extreme projection is tempered by a contrary-moving introversion, not only of the private perceptive experiences of the listeners, but also the far reach back into buried human history. If we do have hidden hearing capabilities, this also suggests that such capacities have always been there, but neglected, or perhaps vestigial processes that have fallen into misuse over eons of social changes. Her music is as much about the unrecognizable perceptive apparatuses of, e.g., Last and First Men (Stapledon) as it is about the resonances of paleolithic caves. In any case, the transformation of the listening apparatus in response to whatever historical needs is bound to be an uncomfortable self-conscious mutation. Her drive to recover latent biological apparatuses evokes the historical image of a people faced with a profound crisis of experience but ill-equipped to address it. That is, it is the proposal of a maimed and dissonant character who feels a profound lack of experience. The liner notes for the first Sound Characters (Making The Third Ear) CD (1999) apparently required a disclaimer to explain that the “ear tones” — what psychoacousticians term “otoacoustic emissions,” a nonlinear distortion effect of the ear when exposed to unnaturally pure, dyadic tones at extreme volume — would not harm the listener’s ears because there was potentially something very dangerous in “making the third ear.” It was pleasurable to the extent that a depth of pleasure can often be found in displeasure. And it is pleasurable to the extent that it is abstract.

The value of the ear tones is not just in the bodily sensation of tone, but in its transitional character which seemed to “wake up” dormant listening possibilities and imagine new ways of hearing. One doesn’t listen to them or just feel them, but has to listen through them, as if squinting their ear. The direct experience of the tonality is not the primary experience, but only a means to accessing self-conscious listening, a self-consciousness which is also not the end goal of the art. The experience of otoacoustic emissions relies upon being self-conscious of how to hear them, of intentionally listening for them, and therefore requires a non-sensual abstraction from immediate sensual experience. In Amacher’s emphasis on “ways of hearing,” the philosophical listener suspects that the point of using otoacoustic emissions at all is not about their sensuality, not at all, but about their being a medium capable of stimulating a form of self-consciousness of latent capacities, almost as if it’s merely a medical stage in the development of a listening prosthesis, but without fulfilling it (Amacher would later design listening prosthetics). The content of the work is not directly what is heard or felt by the body, it is geared towards what could be heard. It is almost as if Amacher’s art is an art of screening tests for new humans to be retrofitted with extended musical capabilities. Her Music Rooms during the ‘80s contained hypothetical Petri dishes growing exactly these types of new humans. Self-consciousness — the listener taking agency over their own perceptual capacities — is a primary value for Amacher, as a means to an end.

//

Beethoven’s Big Feet Stepping Toward God

Amacher’s writings constantly emphasize individual experience as mediator of a world in transition. A meditation on John Cage’s music is also a manifesto of her own redemption of individual experience as a transformer of social life, and on a scale and breadth of time that is nearly unimaginable today:

The completely personal world, the world of revelation, of reception, of your stepping out opening doors! Imagine men some 50 years from now — no longer enslaved to work — imagine what they will be doing. What we do now is preparation for this state. It is mind-cleansing, purifying the head and heart to receive — sensitizing the mind-heart to every nerve — perceiving not a closed universe but a universe in time — reaching back to when “Enitharmon slept, / Eighteen hundred years. Man was a dream!” Beethoven’s big feet stepping toward God is this to me — revelation that steps out inducing this experience of time and creates a relation for man, identifies him with his imagining source, prepares his mind for love — to that distant civilization when man’s main occupation will be as guest and as host to men of his own planet as well as to other life forms. When men are gods to each other! The final exchange! (62)

//

Non-Being and Technique

Close acquaintances might verify that her work was not quite as “scientific” as it appeared to the public, a realization that, for the adepts, is both encouraging and discouraging: for if such techniques could not be objectively taught, how then could one ever learn this new music? While on the other hand, the fact of its non-rationalization could be deeply inspiring in the implication that anyone could stumble into a profound technical discovery given a certain commitment to critical listening. And herein is exposed a problem of the “sound art” for which her generation is responsible, and about which Amacher became ambivalent: it emphasizes learning and knowledge where there is no objective methodology, no school, it cannot be taught or imparted universally, even as the demagogues in the electronic music and sound art propose to follow the “pioneers,” tediously offering classes and tutorials teaching static tropes and techniques which lead to mere derivations unworthy of the expansive art of Amacher’s “mind-heart,”, and continuously monumentalizing its origins, which means obscuring historical consciousness through deficit of interpretation, rather than Amacher’s art of exposing what was always present but latent. How quickly it’s forgotten that the smart “pioneers” have always ultimately become the sharpest tools of technocracy. That sound art is without foundation is not to suggest that it ought to be more rigidly formalized, which would probably (continue to) lead to an industry of charlatanism. Indeed, as will be speculated later, sound art has always been an effect of rigidity and not the cause.

Amacher instead — or at least simultaneously — embraced the image of the singular, intuitional imagination à la William Blake, the one that postmodernism and its 21st century naturalization by the millennial cultural left has theatrically pretended to liquidate. Amacher’s heroically singular visions that lay far afield from all that is known and relevant, which lived in speculation and electric potential, which she courageously followed in her protests against reality, the lyrical aspect, are significant features that inspire her adepts, though often not with much reflection on those qualities per se. Her selected writings return attention to these overlooked aspects. What kind of detachment of mind, social dissonance is required to imagine and value a world in which people communicate by screaming ~2 KHz sinusoidal chirps at each other? Any attempt to posthumously inject her with “relevance” to current cultural standards is to paper over the social magnetism of her dissonance, to ignore an inherently critical spirit to given standards and cultural norms because it had the eagle’s eye for what is far. She has been identified as a cyborgian, otherworldly presence; Arthur Jafa called her a “witch,” in the best sense. She is nothing if not spectral, in the literal synthesis of the sound characters as well as in the philosophy of listening for ghost tones. By all means her value is in the voluptuousness of something non-existent yet deeply human, much less reducible to feminism, the “body,” and other neoliberal dogma that listeners, critics, and adepts tend to fall back on when confronting the incomprehensible. The social artists who justly complained that her death was due to lack of institutional care at Bard also have to reconcile her character as one that transcended institutional consciousness, if only in appearance. Just how, exactly, is an institution supposed to care for a cyborg or a spectre? How, exactly, is a bureaucracy supposed to nurse a manifestation of non-being?

//

Standing on the Shoulders of Spectres

Amacher’s “third ear” seemed to so quickly rigidify into a cheap effect instead of the lyrical expressivity of a character that is only revealed in the tension, adjacency, and simultaneous presence of other characters. (Analogously, it’s a trend for painters to pursue the most dense pigments to get the most vibrant colors, ignoring the traditional knowledge that colors only become more vibrant when adjacent to other colors.) There is no shortage of artists who have tried to “do” otoacoustic emissions, who have tried to turn her so-called “greatest contribution” into a positive program, ranging from Florian Hecker and Jacob Kierkegaard to Doron Sadja’s VST instrument, and many others including my own (unpublished) compositions from the ‘00s. The common ideology of Amacher as “obscure” is not quite accurate: she’s as famous and influential as any avant-garde electronic composer has ever been, and in a moment when electronic music is a booming industry. Amacher played Woodstock ‘94. If she was obscure,” it was because that’s how people wanted her, and probably is endemic of the current idealization of the underground genius, an idealized undergroundness that is simultaneously perceived as dogged necessity. The marginalized victim card that electronic musicians play in the electronic music game — maybe once true, but only maybe — is contradicted by the ersatz electronic music ideology that equates it tout court with aesthetic progress and have created a positivist, mass industry upon what one can’t help but see as an attitude of standing on the shoulders of spectres. What stands is to question what Amacher’s role in expanding this affirmative, monumentalizing culture was, if any, and if standing on the shoulders of a spectral illusion is even possible, let alone why it’s desirable.

//

Aftersound — or — Aftermusic

Not only was Amacher’s hermetic social character a contradiction, but everything about the art itself was plaything of illumination and discretion. While the music was nothing if not palpable presence, the purely physiological, “bodily” music was contradictorily dependent on what wasn’t there, the “ghost tones.” The magic of her work is not in the body, but in the rare specificity of how non-being was manifest, the conjuring of ghosts and spectrality into something unusually tangible and productive. So crucial to her music is the concept of the aftersound, the phenomenon of tonality lingering in auditory perception long after it has ceased, that it’s difficult not to perceive in the aftersound concept an allegory for music’s bygone life, amidst its death in our era. The long fade outs of the music into moments when the listener can’t perceptually discern if the performance has ended sensualize the threshold of art and life so central, and yet so confusing, to art over the last century. This aftersound motif can be perceived as an extension of the red curtain or fifth wall just as much as it can be perceived as its dissolution. Amacher sensationalized this speculation, not the answer. The perennial confusion around the issue of music’s tradition and its relation to life is perpetuated in the common presumption that Amacher’s art is not music, but also simultaneously an expansion of music. Which is it? Seeing as how she sought to manufacture in Petri dishes new musicians, the latter seems more accurate.

//

Rigidity

There is something of Morton Feldman’s elusiveness to a type of overwrought formalization in Amacher, who also had to confront Stockhausen’s industriousness in manufacturing culture. Much is made about Amacher’s working under Stockhausen, and how she ultimately outcomposed Stockhausen, doing what he wanted to better than he could (Cimini). The verifiable truth in such an interpretation is less notable than the common assumption that Stockhausen is, or was ever, the high standard of music composition; for at least Adorno perceived in Stockhausen and his school the rigidification of music, a controlling spirit of domination and normativity, a pretentious pseudo-science out of a simplistic conflation of music as math, exemplifying a “music that can only be understood with the aid of diagrams,” a traditional “system-driven music not so very different from the false notes arbitrarily introduced into the neo-Classical concertos and wind ensembles of the music festivals of thirty or forty years ago,” in other words, certainly not the triumph of new music that seems to be so monumentalized — and just as predictably rebelled against today — in the mythos of the electronic music industry. The extent to which Amacher “improved” Stockhausen could also be seen as the extent to which she perfected a positivistic rigidity. She inherited a musical value system that thought “because the musical material is intelligent in itself, it inspires the belief that mind must be at work, where in reality only the abdication of mind is being celebrated.” What are we to make of Amacher’s obsession with “mind”?

//

Maryanne Amacher at work on “Sound House” in 1985. Courtesy of the Capp Street Project Archive.

Objectification and Characterization

By rigidification Adorno meant something like thingification, reification, which could be seen in, e.g., graphical scores and diagrams, with their new perception of time as a function of space. The ideal of “sound objects” that can be manipulated and moved around — sound itself as an object — is central to the way composers in this era came to think about music, and persists to this day, everywhere. But it is by no means limited to modern composition, and also evident, for example, in the way people began to “listen” to all forms of music as if it were something engineerable, and something to be possessed. Adorno observed the whistling Beethoven fan who in this paradigm reduced vast, dynamic music and sonic processes to soundbytes that seem almost as if they could be pocketed like a trinket, and underscored the deadening of music required to accommodate this consciousness. This formalization is the social situation into which Maryanne Amacher started to compose, and which, I think, she struggled against, as well as sometimes for, in various strange and abstract ways in her attempts to make. e.g., a Living Sound (Patent Pending). Her longing to “spray sound,” for instance, expresses this contradiction of possession and liberation, not to mention its sexual overtones. Amacher’s valuation of Cage and Beethoven’s induction of “an experience of time,” her developing a concept of “Life Time,” are attempts to reconceptualize and resensualize time in music at the historical moment of its impasse and shouldn’t be needlessly metaphysicalized. The technical requirement of extreme amplitude for the ear tones could also be perceived as an insistence to not reduce music to a cute trinket, to play it as loud and dynamically as Beethoven once heard it, not to limit one’s own experience to one of ownership, but also to expose it to being owned by something more expansive. But this could also be interpreted as an unconscious value of authority endemic to music experience in our era. Perhaps no one since Adorno has been so attuned to the crises of experience posed by the recording medium, the tendency for musical fixation which has today engulfed the concept of music, and limits certain forms of experience even while it seems to open up others. But in terms of “sound objects,” Amacher’s contribution to musical consciousness was her reconceptualizing the sound “object” as a sound character. For in this reconceptualization, “sound” is not a dead and reified object to be manipulated like a puppet, not some absurdly hypostasized ideal thing-in-itself that exists outside of human activity, not some one-dimensional metaphysical point to be pseudo-scientifically positivized and rendered as religious shrine presided over by vapid priestesses and new vibration authorities, but a heterodox mix of characters as distinctly individual as they are integrated, which combine and interact to create secondary experiences. For in this philosophy, so-called “sound” is given life by placement in tension with other sounds, analogous to the way human beings are given the (possible) conditions for individual transformation through mediation by public life, which would continually develop in dramatic tension, and whose whole set of dynamic relations would not be reducible to the style of one of its parts. I do not think she made a lot of progress in this regard, not only because her “greatest contribution” is typically perceived as the musical use of otoacoustic emissions and the resultant meaninglessness that comes with the sensation of tone alone, but also because the mixing of these characters was very simple, crudely adjacent, perhaps not as dynamically arranged as she imagined they could and would be. There is a reason why her Sound Characters, live and recorded, were not homogenous explorations of a character isolated in one dimension, even though she could have successfully packaged her ear tones alone as such, but instead were composed.

//

Amacher as Composer

With the attention around her genius, Amacher’s character as a composer runs for the dustbin. Not only as a composer in the general sense, not as a “composer” in the way we today think of them — authoritarianly — as authoritative experts, but as they were once theorized to be, as naive mediator of concept and material, the composer as an incomplete task, but also more specifically as a composer trying to compose with such extreme ambition in the moment of its extreme difficulty, and whose art inevitably expresses this historical crisis, does Amacher speak to musical life. And the millennial cultural left’s status-quo taboos around modernism, and the consequential blindspots that ideology manufactures, render this potential reflection a missed opportunity — for few composers were so driven in extremis, so far afield from composing music proper, due to an acute sensitivity to the historical crises of music composition, in attempts to create in a more true, free, and living way. Amacher’s life task was to “compose on the spot” spontaneously with the “unfettered freedom of genius, of Beethoven,” a profound early statement which stands out because it shows how rare and valuable such spontaneity of composition had become at that moment. It is a spontaneity that Bill Dietz has revealed came into full fruition in her later performances not long before her death, as she would point to musicians and command them on the spot to play the tones that would trigger the ear tones, which she had mastered. The “Adjacencies’” “score is not ‘graphic’ in the sense that its shapes are suggestive of musical or acoustical interpretations. It is actually a ‘negative’ notation, with regard to interpretation and visual information” (39). Perhaps no other artist, barring LaMonte Young or Adorno (if we finally admit him as an artist), so directly examined and felt the impasse around temporal extension and the frigid music turn in the mid-20th century, was so keenly sensitive to the way in which the urge to more organization — what Amacher termed “horse music” — merely led to a more calculated and dead music, and whose projects became an informal music of some sort. They can be considered sensual negations. It was no mere eccentricity, and not merely the reproductive limitations of the medium, but as a living spectre of music’s bygone spontaneity that Amacher refused for years to release music as fixed recordings, something to be passively downloaded into the listener’s repertoire of shallow entertainment “ice cream truck” listening habits. Yet it doesn’t appear to be the case that the spatially myopic sound art sensorium resulting from her critique (as well as many others) of the impasse of temporal music has cultivated the free world she envisioned, so much as expressed a brilliant, disorganized, and desperate effort to salvage what was worthwhile from western classical music by exposing what were, abstractly and necessarily blindly, believed to be its blindspots. For even in these three extreme artists and thinkers, the issue of time, and its resultant suppression by the spatial turn remains unresolved — Adorno could only critique it from the standpoint of an epigone; Young retreated into orientalism and religion, and Amacher would slowly drift further afield from this primary question, occasionally drifting into pseudoscience. In her New Music Box interview, she explains that a primary motivation was to break the spell of the “what follows what next” tedium. And rightly so, the concept of time is generally reduced to a “what-follows-what-next” tedium.

//

Unmasking History

Yet it doesn’t inherently follow, in Amacher’s case, that traditional, temporal classical music is entirely bankrupt, as demagogues now otherwise presume, an overreaction or displacement of crisis which might now be nothing more than a mask itself. “The psychologists are familiar with the alacrity with which people hold time responsible for matters which they do not wish to examine too closely or for which they want to disclaim all responsibility.” Not only in the fact that her installations and performances more deeply relied on unfolding narrative structure, for instance, did she continually pursue an art of time, but also in her clarifying that the “third ear” discovery was not a new phenomena, and rather one that was always present, yet masked, by the complex timbres of traditional instruments in classical music performances. And what are we to make of Amacher’s interest in psychoacoustic masking? Was it merely auditory, or was it also allegorical? In her Additional Tones Workbook she draws attention to the design of the organ, which has always had a stop to add pitches a fifth or third above the note being played, so as to reinforce notes an octave below the note being played. To think through music history in such a sensual way places her into a different realm than mere futurism or progressivism, for example, portraying a mind capable of thinking in many different historical directions than just forward, and in many overlapping, simultaneous ways. The point of Amacher’s “endotonal” music — which she defined in a proposal for an original composition for the Kronos Quartet as compositionally acknowledging the double function of the ears to both receive and transmit sound — is to render mystified music perception processes available to the self-conscious “listening mind” that hasn’t yet been developed enough to take advantage of the full gamut of human listening experience. Moreover, the “double function” suggests, like Baudelaire’s poetry, a composition based on dissonant contradictions. The self-consciousness of using something that was only unconsciously instrumentalized actually changes the thing into something else entirely. There is always something latent lurking in the background of her work, an untapped potential of emotional listening experience that is occluded by traditional music, even as it has only yet been cultivated by that music. To assume that her accusation of “horse music” — the predictably temporal aspect of classical music that is its blindspot — is merely an insult flung at tradition is to miss the deeply historical point that artworks unconsciously express a social need that is yet to be clarified, which has always been the dynamic of art. Her insistence on moving beyond horse music suggests that new social needs are not yet being fulfilled by music. Her figurative sound characters do not ever fulfill these needs, but point to them obscurely. The implication is that the relationship of any new music to history would be one of clarification. It portends to isolate and re-present music history’s most valuable but hidden elements, to unmask history, and in so doing would require the transformation — not the erasure — of the entire consciousness of music tradition into something quite unrecognizable from our current consciousness. However different in content, a statement Amacher made about loudspeakers illuminates the way she thought about necessary but undesirable reality, history, and material — the insufficient loudspeaker is not to be featured and exposed in the exhibition, nor is it to be hidden and concealed. She finds it necessary but nearly impossible to actively negate it, to work through and not around it. This critical practice is endemic to many of Amacher’s generation, for instance in Ligeti and many more who looked back to medieval polyphony for inspiration, or who sensed something incomplete about music. It’s no mere colloquialism or naïveté that Amacher compares herself to Beethoven in her writings. The central question of many of her installations, which featured halls of composers dead and yet to be born, was What is music for humans and why is it everywhere?

//

Petra

Yet it’s doubtful that many adepts will share this interest in a critical music history practice that would boldly challenge conservative music thought by deciding and interpreting what they feel is most important in music history (though they will likely continue the non-committal antiquarian music historiography). The interpretive faculty, for lack of a better term, is constantly undermined. Blank Forms’s recent historical salvage and publication of “Petra” — a radiantly dissonant piano composition performed in 2017 by Stefan Tcherepnin and Marianne Schroeder — is an interesting case study. On the one hand it is tellingly mute on the matter of its post-Schoenbergian composition (at least in the online public edition) — for if there were educational notes they would have to reconcile a practice emerging out of interests in Schoenberg, an admission that is generally taboo — because it is true. Instead, the emphasis is on the acoustics of the church and the science fiction that inspired it. And in many ways rightly so, as Amacher, ever the polymath, was inspired by science fiction, even writing science fiction narratives herself, as well as acoustics, obviously, and of course attention should emphasize and develop the content as she envisioned it and on its own terms. But the “supplanting” form of historical consciousness does little justice to Amacher’s values of simultaneity. It’s tempting to interpret “Petra” as one of many instances of the pretentious 21st century “neo-classical” music that enshrouds itself in false modesty even as it tends towards a classical restoration, a sentimentality which is quite out of tune with Amacher’s radically alienated music. From this perspective, “Petra” would be a byproduct more of our era and its justifiable aporias around irony, its overcorrection by grandiose claims to sincerity, resigned melancholy, or, more to the previous point of historical consciousness, the tendency to take refuge behind historical monuments (like classical music) without changing them, as a means of justifying the existence of art at all in an artless world. “Silicon composers” have long struggled to convince both lay listeners and professional musicians that they are indeed composers worthy of the concept, and often feel pressure to retrofit their work to the known references of traditional instruments, analogous to the way their compositional ambitions often need to be packaged up in technology to sell it to opportunist curators and bureaucrats. What are we to make of such a piano piece when Amacher’s aesthetic values were otherwise focused on the elimination of identifiable instrumental timbres? Is it a failure of performance that couldn’t bring about the purely resonant acoustical life? Is it an accommodation on Amacher’s part, a necessary but frustrating attempt to legitimize her work? The Foundation’s just protest about the centrality of the score in “Petra,” as a correction to the NY Times’ notion that there wasn’t one, perhaps expresses a form of this trend of justification, too — the overwrought centrality of “scores” in 20th century music was always overdetermined and expressed the rigidification of music. In her 1989 Ars Electronica presentation, Amacher herself laments the unfortunate predominance of scores in later classical music, which drew attention away from the practice of earlier composers (e.g., Vivaldi), who were once more in tune with “the listener’s music,” or what she later terms “endotonality.” The incompleteness of Amacher’s score is maybe not inherently a bad thing, and could be perceived as vestigial from an era when music lived a freer and more intuitive life.

“Petra”’s performance in a church is also specific to the many instances of experimental and neo-classical musicians performing in churches these days, often a pretension to mystique and a quick-and-easy way to make music sound more solemn and profound, just as electronic musicians tend to lazily slather reverb on dead sound objects and assume some shady and boring role of high priest. To use Nietzsche’s allegory, such cavernousness relies too heavily on echo to give shape to a dreary pedanticism, instead of exuberantly wielding the cutting-edge of a new and terrible sonic sword, a sword that Amacher forged out of the ashes of bourgeois music as few else have done. On the other hand, Amacher was a composer in the immediate wake of bourgeois music, so it is also fitting, as many such pieces of her generation were composed electroacoustically, tape with instruments, and not merely as an accommodation either. And Schroeder performed “Petra” like this with Amacher in the ‘90s and as she envisioned it. If it is an accommodation — and it’s an open question whether or not it even is — it was Amacher’s accommodation. In an interview with Schroeder, reference is made to Amacher’s interest in the performer recapitulating piano learning through “Petra,” suggesting again that Amacher aimed to unmask known techniques, to unlearn training so as to relearn new primary modes of experience. Despite Schroeder not recalling this memory, it underscores again that Amacher aimed at some form of primary musical knowledge. The issue with “Petra”’s release is maybe just that there’s an extra sensitivity to Maryanne Amacher’s music reinterpretations, and what is true or untrue in them, which is a testament to the rare conceptual sensitivity and radical speculative quality she tends to foster in her listeners. As a “Temptor-God,” all interpretations of her music are split open and exposed to a fantastic indeterminacy. It will be interesting to see how her work is staged and interpreted going forth. “Petra” is potentially profound, and it’s hard not to feel inherently grateful for Blank Forms, Tcherepnin and Schroeder (who know Amacher’s visions as well as anyone) for audaciously publishing such a challenging work because it is rare to hear Amacher’s buried compositions, but also because it underscores Amacher’s often-overlooked commitment to an historical consciousness of music and what many composers today assume, often tendentiously, to be its foundations in the church — yet it’s unclear what it all means. It is specifically its character that is unclear. Even deeper than that, it’s unclear what kind of critical attention could make it as meaningful as listeners in private suspect it should be. I think that it would require some form of critical music history practice to even approach the important question of a composer’s motives in that complicated era, and even that would likely not be adequate to save it from falling into easy, affirmative listening, an ultimate destination it may have been fated to from the outset. Still, “Petra” and the other stagings of her work uniquely point to the possibility of this critical interpretation of music. From testimonials, it seems that audiences heard themselves thinking about music, something oddly rare at music performances. Listening to one’s listening is not something that will ever really be popular, as Amacher hoped, in society as currently arranged, but will appeal to the musicians who only influence other musicians (avant-garde). It inevitably partakes in the spell of musical knowledge that is ritualized into underground enclaves in the era of division of labor, and which too many sound artists and composers render a virtuous end instead of a necessary baseline.

//

Reactivating Dormant Cells

Amacher’s music is a prism through which music history breaks up and refracts. Her own term is “reactivating dormant cells.” Bill Dietz wrote that: “It was with Maryanne’s generation that history, meaning, and even narrative made their dramatic, decisive, and yet often confused reappearance…. Her recent unrealized proposal to create a new form of book that would facilitate visualization of Goethe’s “physiological colors” in association with “their corresponding sonic twins: the neglected ‘additional tones’ of music,” would have made this jump backward to see forward explicit. The jump backward to see forward. Amacher’s “The Music Rooms” in the ‘80s used props from historical operas. Imagine the allegorical significance for music at large in the image of the mirror from Berg’s Lulu lurking in the background of her music rooms, reflecting through the looking glass of history. She recreated Freud’s couch. Her original performance of “Adjacencies” followed three interpretations of Webern’s compositions, one suspects, because Webern was the composer who inspired the Stockhausen school, though in a way that superficially interpreted his music as a project of extreme technical control instead of, e.g., inimitable lyricism and obdurate intuition. “Adjacency” can also allegorically describe her historical position. Amacher’s insistence on simultaneity and “joining” echoes Adorno and Young’s valuation of what made Schoenberg so radical and compelling to begin with — formally but also inherently socially: the integration of previously unrelated, disintegrated, and tabooed tones.

I made Audjoins [“Adjacencies” comes from that series] so that worlds of sound could be joined. They receive each other, interrupt, interact, and bring the unexpected to each other. What previously could not have happened simultaneously in the same place, either because of distance, as in the case of countries, or within one composition because of sound levels in one room, is now possible through electronic means. (Amacher, via Cimini at Blank Forms)

Likewise, her adherence to the opera form at all is surprisingly non-futuristic and traditional, and her attempts to modernize it into “media” operas could also be perceived as an early instance of the now countless desperate efforts to legitimize art in an artless world by recapitulating its most ambitious historical moments: the Gesamtkunstwerk is most idealized in an era of helplessness. It is hardly possible that Amacher created an opera worthy of either its historical concept and practice, or her own lofty standards and revaluations. The unique values she seemed to place on what one acquaintance called “opulence,” but which might better be conceptualized as voluptuousness, coincided with the mass rejection of her music. Cimini’s argument that Amacher tried to redeem opera through emphasizing the “body” in the tradition of opera could offer one reason why: opera is by no means limited to a bodily sensorium alone — as necessary and implicit as that may have been to opera — but was simultaneously profoundly emotional in a way that ascetic moderns and authoritarian millennialism can scarcely comprehend. The emotional stunting endemic to our technocratic society tends to render emotional intelligence a blindspot, a blindspot that is often filled with abstract ideological projections, and the pseudo-scientific body sensorium aesthetic of much 20th and 21st century music reinforces the tendency towards shrewd formality, or conversely the reactionary need to downplay it via some meaningless carnivalesque spectacle. Even so, the obvious presence of an emotional affect, however vague in Amacher’s music, is unique amongst electronic musicians and especially rare in the demagogic type that the medium tends to manufacture. Her notes explicitly say that she desires to make a music where people cry because it is “unheard of” and develops “too-sensitive” areas. While it’s more likely for audiences to stand in awe, instead of vulnerability to her big sound and towering character, where the music does reach emotional vistas is possibly due to its “unheard of” eerie spectrality, as well as the strangeness inherent in listening to simultaneous things that are not meant to be heard together. It is the painful otherness of an integrated life that touches and wounds.

//

Spectres

Much of the late 20th century avant-garde migrated into some form of spectralism. The Selected Writings reveals Amacher to be an early theorist of this musical form before it had become a “movement.” As early as 1965, (though also perhaps even earlier than recorded here) Amacher writes pieces (“Adjacencies,” Audjoins) focused on the relationship between harmonic and inharmonic spectra, using amplitude as a means to allow the partials of inharmonic spectra to align (or misalign) with composed harmonic spectra. It evidences an early interest in the dynamics of masking and revealing, whose aim is...

to magnify the “music” which begins to organize itself within the multi-frequency-intensity fluctuations common to inharmonic characteristics, modeling in a larger scale way the kind of “singing” and melodic contour heard when putting your ear close to a cymbal or gong while sounding.

These melodic contours — “rhythms and singing” — result from vowel-consonant-like formant patterns, produced by interacting micro-changes developing within the spectral components.

Here, too, Amacher is bound up in a problem of our culture more generally: the who-did-what-first question. Since electronic music is dependent upon a progressivist value of innovation in a property-based music culture, there are constant claims and quibbles of who-discovered-what-first, which gender of composers is more radical, what faction was more ahead of their time, etc., concerns that hardly seemed to weigh on Amacher’s art directly. Consequently, the historical question of why a certain style or aesthetic value emerges at a given time, and also cuts through broad cultural, institutional, and regional boundaries is often neglected, in favor of the transhistorical and phenomenological values postmodern sound art often defaults to. For it was not just that Amacher or the spectralists “innovated” this new music form out of the thin air of a pure, composerly mind, but simultaneously indicates that the history of music itself needed to take this turn, and worked through various composers. Yet spectral music has hardly magnetized the masses, positively or negatively, in the way their inspirations — Schoenberg et al — were able to do. The legacy of the avant-garde — its growth out of bourgeois music, its extreme ideals, and its failings — is sedimented in Amacher’s hermetic sound character, and she inevitably took many of its secrets — or at least her interpretations of them — to the grave.

//

Monolith of Evanescence

One of the problems of the spatial turn in music is that the recognition of artworks as historical documents (Benjamin) is liquidated, intentionally or not: we’d expect that whatever Amacher’s critical attitude may have been to music history would be evident and mediated foremost in the music form itself, but the spatial turn deemphasizes these document forms in favor of immediate sensation and an unmediated ambient dispersion of a mysticalized “sound” in which the listener is supposed to be awestruck, instead of understanding (standing under). A history of music in the spatial turn is oxymoronic. Or at least inappropriate. Though the acoustic state of the sound art emphasizes presence above everything, and rightly so, for it is the present which is the content of all historical consciousness, it nonetheless recedes into legacy, theory, projection, futurism, and abstraction. Sound art contradicts itself in the necessity of its perpetuation in abstract, arguably dogmatically abstract hypotheses. Amacher’s writings are incapable of transcending this incoherence, and can be read as exegesis of not-nothing. It’s not yet something, but it’s also not nothing. Considering the obsessive and restless nature of her pursuits, the visionary (there is no word for its analog in listening) who desperately hoped to create a new music paradigm and new era of expressive communication between audience and performer, and person-to-person, any affirmation of this “liminality” as an end goal, instead of the transitional character she cut for herself, does Amacher little justice. Amacher’s character — as a monolith of evanescence — which refers as much to prehistoric barbarism as to the far-projected future freedom of humanity, which converges in the present as something fungible, transitory, and which requires a curator of one form or another to barbarically point at what’s happening, and to turn the authority-seeking listener’s head for them, instead of something profoundly self-evident and as individually introspective and expressively communicative as she hoped it could be, is a haunting problem and only rudely points to solutions.

//

Magnifying the Expressive Dimension of Music

How did Amacher ultimately feel about being identified as a heroic “sound artist” instead of a hardworking composer who underwent a heroic rescue mission into the deepest undercurrents of music history? I imagine it must have haunted her for her music to not be considered as music at all, even though it was also very specifically nothing but music. Her much-lauded interest in architecture and acoustics was in “magnifying the expressive dimension of music,” not in the circumvention or liquidation of the expressive dimension of music, as is often implied. In Amacher one hears echo of Schoenberg’s criticism of her comrade John Cage: that he may be a genius but isn’t a composer. It actually says something that the naive and hardworking Schoenberg held a higher view of the composer than the genius, a value system that is likely reversed in the popular imagination of today, and one in which the supposedly eccentric, “mad scientist” Amacher is bound up in. One suspects Amacher may have felt similarly to Schoenberg regarding herself, resignedly accepting her esteemed and meaningless status as the obsolete genius which eclipsed her musical ambitions. And in our era the genius is often, too conveniently, a technologist. It hardly seems significant to frame Amacher’s art in terms of technology, though her complicated relationship to technology is a bit of a lightning rod for how artists relate to our technocracy today. The technological aspect of her work was first of all deeply suspicious, as it wasn’t “about” technology, per se, but used technology for ulterior aesthetic motives that were confounding, non-technological, quasi-magical, even vaguely ritualistic. She was of a generation of the conceptualists who have only posthumously been called “mystics” rather than the shrewd realists that they’re often considered. Amacher was apparently obsessed with William Blake. Like many great modern artists, she was even considered by some to be somewhat... insane, perhaps having more in common with, e.g., Artaud than the rationalized music technocrats of our electronic music cottage industry. What is to be made of a score in which “The music may be live musicians transmitted through the fire” (91)? The fact that Amacher’s “sound art” was resigned to seek support through institutional grants is more a testament to her critical failure, not her success, even as artists today are likely to fight over such grant scraps that are too often, and in an authoritarian way, considered prestigious. It shows how in the era of the wake of the avant-garde, the technocrats will quickly step in to claim an artist, or art in general (the technocrat vulgarity of NFTs only caps this long-standing historical process). Amacher’s telematic works from the 60s–80s that excitedly announced the dawn of the internet age can in retrospect also be seen as the cutting-edge of what has merely become a complete technocracy dominated by nihilistic media and the final effacement of art as well as the individual imagination Amacher valued so highly. And this despite the fact that her basic interest here was in the shared consciousness of tonality in different geographical spaces; i.e., inquiring into any hypothetical objectivity of tonality to determine if some sites had a fundamental tone, and if so, what did this mean for the consciousness of people in those discrete places. Or was the fundamental tone the effect of a given community? What could happen when played simultaneously? Inquiries like these could have hypothetically been pursued without technology, perhaps even better in essay form, or at least without so much emphasis on technology. Why did she feel it necessary to carry out such inquiries in so technological a manner? In Amacher we see another example of the way singular artists, even the most heroic and defiant artists, are blinded to, or blinded by, broader social forces acting upon and shaping their work. The task is not merely to make a virtue of such “socially constructed” situations — a meaningless academic platitude but also often a capitulation to an unfree reality that artists, at least, and hopefully, desire to transform — any more than it is to blindly monumentalize the singular artist who stands in successful resistance to the social ornament. In the contradictory, elusive, and perhaps tragic character of Amacher, we see both, and neither, a capitulation to reality, or the resistance to it. What it is is unclear; an attempt to overcome it on the terms of its current unfreedom? A circumvention? Perhaps the technology was merely the thick sheet of ice through which she and her listeners had to plunge for a sweeter intelligence, but by no means to reproduce its austere coldness? Her own words address this:

This is why electronically, I feel it's necessary spiritually to make the powerful personal — to work hard and fast to turn what might be abused as control elements — what might be used to exploit the senses — to transform this material away from control into openness (all art has traditionally always done) — what we have always done. In painting, in all the arts, this has always been the criteria for me.

Her genius was of the heart, not of technology or electronic music, and in many ways she could be framed as anti-electronic music, in the way in which she identified its tools as the site of unfreedom. Analogous is the way 19th century poetry was not about language, but used language against itself in an era of linguistic barbarism and academic “control.” Just as the words on the page are not the poetry, the electronic tones Amacher composed are not the music. It is an indirect and subcutaneous art.

//

Techne and Aesthetic Resignation

Yet Amacher’s interest in computers as a compositional tool illuminates the exuberance of the frontier on that narrow historical threshold just prior to its domestication. In one interview, she states that her initial turn towards computers was due to analog oscillator “drift” which rendered them untunable for her purposes and by implication any serious composer who wanted to pursue true experimentation and extended composition. The “silicon composer” can achieve “faster” results towards a “personalized framework of time” that broke through the tradition of what she called “notes without ears,” wherein “composing usually amounts to procedures of simply rearranging and modifying existent musical figures.” Through the exhuming of her archive we now learn that her ear tones were created by Marvin Minsky’s Triadex Muse, one of the first algorithmic music machines. The Muse was a failure, having only sold a couple hundred units, and was extremely limited in its sonic capabilities, outputting a simplistic square wave (and Minsky too has fallen out of favor with relevant AI scientists today). A different contemporary example could be found in Laurie Spiegel’s programmed music of that era, which prioritized simplicity of tone over timbre and sound color, so as to develop a more compositional consciousness. Such acute awareness to this problem is reminiscent of Adorno’s critique of much electronic music, and much modernist and premodern music as being meaninglessly obsessed with sonority. It is a critique that, coming full circle, was originally articulated by Nietzsche in response to the turning away from acute expression into what he called “tone poems.” (Meanwhile in our era the Völkisch electronic music youth are obsessed with repeating the retro analog timbral drift in the vintage synth cottage industry whose only ambition appears to be making the world into a cottage of tone poems). Amacher was motivated by a will towards sonic transparency, e.g., in the use of psychoacoustically “pure” tones, whose affect is as startlingly expressive as it is vulgarly simple, but only as a means to define distinct characters emergent out of the ear. The instrument was not the synth, but the listener’s ear, an ear which was played like a sounding board by the synth. It’s quite a multi-part, distantiated process, when you think about it — composer controls the -> synth plays the -> ear. It’s rare to find a musical artist in our era with such inherent irreverence for tone poems (or who’s irreverence is not reactionary a la noise), and who senses a possible beauty in vulgarity. With all of the emphasis otherwise on sound and space, it’s strange that Amacher opted for the Triadex Muse, as it emphasized temporal extension and melodic development above tone color. It is imaginable that the Muse was hardly able to manifest the ear tones as Amacher probably heard them in her head, and that she had to make do with the material available to her. On the other hand, it’s conceivable that she only heard the ear tones via the vulgar simplicity of the Muse, and that it was her keen listening faculty which was able to extrapolate from a happenstance encounter, sensing possibility where many less sensitive, and more formally directed minds would not. What it must have felt like to crank this new monstrous machine to such intense, voluminous levels never heard before, in the privacy of her experience! What courage in dissonance must have been required to withstand the alienation inherent in such voluptuous expression! Anyone who has ever dared for even a minute to conjure a third ear music knows the extreme resistance to such a powerful, overwhelming, and monstrous aesthetic by those exposed to it. What strength of will she must have had to conjure and maintain! And then to bring people to the threshold of their physical destruction with such fearful dissonance and yet to come back from such wild frontiers with listeners calmed and excited by an unprecedented trust in her sensibility, what must it have felt like socially? To subject her own ears and physiology to such unknown risks, and to subject her psyche to the social alienation those around her must have felt in the presence of such ear tones must have required an insane confidence, belief in her contribution to music history, and willfulness to dissonance in a social moment of contraction and conformity. Anyone who has dared to compose a ghost tone, or to work in the negative space of pitch intervals is familiar, too, with an abstractness of thinking and indirect relationship to material reality that is for a greater voluptuousness of material. It is to access the shadowy realm of material behind material, of what Adorno called the “subcutaneous.” And here, too, the ear tones are exposed as not a new invention, but an extreme rescue mission into the possibilities of pitch interval that has been critical to every major composer we know of. And so too the structure-borne sound work does not propose a direct ideology of how to listen, as if to say that this is how we should be hearing. Rather, it seems to say that the listening experience has been formed by air, so what thought processes emerge when our habituation is suspended via passing sound through structure. Amacher’s art is not about the sound experience itself, but rather the imagination that can be stimulated by experiencing a negative space of habit.

The legacy of such a sensibility should probably be found in artists like Ryoji Ikeda or Holly Herndon, who likewise are too easily pigeonholed into a technologically oriented form of music, sometimes by their own design, and also foreground psychoacoustical effects. But the psychoacoustic sensorium often takes refuge in, instead of exposing a kind of science fair aesthetic, or demonstration of cheap parlor tricks that undermines the composers’ compositional intelligence that seems to be what listeners are truly compelled by. Amacher herself compared the otoacoustic emissions to stereoscopic visual tools, a 19th century phantasmagoric curiosity that hasn’t really been important to art because it partakes in a kind of purely optical illusion. How did Amacher feel about her work being framed as complicit with this very low vibration aesthetic turn of society — “technology” — even as her art seemed to conjure the hidden cosmos itself, as if by magic? How would she feel about being a mother of sound art, instead of a redeemer of music?

No amount of electronic music anthologies, historiographies, or documentaries about the “pioneers” of electronic music will save 21st century electronic music from being pigeonholed into a status-quo, technocrat aesthetic, in part because the conceptual fabric of the “pioneers” and their modernist ancestry was petulantly ripped up, but also because the character of the pioneer is a contradictory relic of the 19th century that will continually undermine itself. With their literal dying away in the early 21st century a critical moment of consciousness goes to the grave, and they should be held at least in part accountable for the impasses we’ll continue to see return, insofar as that generation’s own blindspots led — intentionally or not — to a kind of narrow and dismissive attitude towards history, or an aesthetic resignation.

//

Evocations

The critical paradoxes of reality and imagination bear down heavily in Amacher’s work. There is something about her legacy living on in her writings that is perhaps more to the point of her life’s work: namely that she might now be perceived as a sort of poet, in the sense that the poet evokes possibilities for what aren’t. And again, there is a metaphor to be found in the evoked part of the term “Evoked Otoacoustic Emissions,” for Amacher’s art was one of evocation. In Amacher’s writings she is returned to the original meaning of Nietzsche’s third ear, which concerned the lack of musical evocation in the rationalized writings of the Germans, and which persists in our present rationalized era, the vast administrations that seek to ration art to the masses included. It concerns a capacity to listen to the whole art, not just the “swamp of sounds,” and which is not merely an auditory phenomenon, but also an abstract interpretive capacity. The influence of Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men on her work is telling in its expansive scope of historical consciousness that flickers a barrage of image-riddles of what could be. A billion-plus-year historical scope, with its various revolutions of humanity, our failings and successes, our recapitulations, relearning what has long ago been learned and then rapidly degraded and lost in time, and then recovered and recombined again, anew, from out of the recesses of so many primordial oozes, is exceedingly rare in our value system of myopia eager to prescribe and predict what comes tomorrow, as determined by a mere continuity of the meaninglessness of today. The type of open mind that can think in this expansive scope, that can take a “Step Into It, Imagining 1001 years” and simultaneously enter “Ancient Rooms,” that can live a life of interpretive possibility beyond a what-follows-what-next taedium vitae, who breaks this monotony open and becomes the caesura figure inside the eversame, the caesura as prismatic wedge in petty and small-minded ambition, whose historical consciousness is not continually downgraded to antiquarian jargon or academic restoration projects, but upgraded to a living and ambitious figuration desperate and at pains to expose possibilities in the present, who risk “tone deafness” to the status-quo because they have the capacity to hear combination and difference tones in the racket of our prehistorical din, is needed more than any formalized sound art or pseudoscientific sensation of tone or mob-curated politesse. The scope of such an imagination is already far more socially mature than the relevant and engaged who affirm the taedium vitae and chaotic happenstance of mundane current events, they are the ones who imagine life itself. The editors implicitly understand this when they say “the work she was fabulating was paradigmatically incompatible with the world as currently structured along gendered, racialized, temporalized, capitalized fault lines… She did everything she could to articulate and offer us an ‘elsewhere,’ an ‘otherwise’ in, or adjacent to, the world.” Amacher’s writings are filled with suggestions for how things could be, should be, an articulation of what isn’t, an evocation of non-being, the tragically slipping grasp on the highest of standards, fantasies that in another era might not be fantasy but in our era are rendered painfully absent. The suffering of Amacher’s visions is now apparent in her rebirth, now taking up residence in the spectral pantheon of the utopians, an army of vanquished eyes floodlighting the present darkness of a quibbling humanity. The image of Amacher in her rebirth — one of negation — is true to the genius of her heart.

//

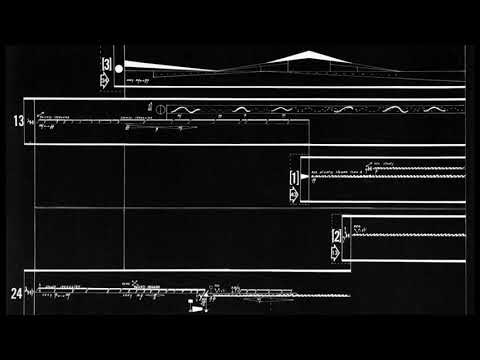

Maryanne Amacher, Adjacencies (1965)