"To Be Clear at All Costs” ~ On Morton Feldman

The revolution we were making was not then or now appreciated. But the whole American Revolution was never appreciated either. Not really. It has never been given the importance of the French or Russian Revolutions. Why should it be? There was no blood bath, no built-in Terror. We do not celebrate an act of violence-we have no Bastille Day. All it was, was, "Give me liberty, or give me death." Our work did not have the authoritarianism, I might almost say, the terror, inherent in the teachings of Boulez, Schoenberg, and now Stockhausen.

- Morton Feldman

This year marks the 250th anniversary of America, and what better way to celebrate than considering one of America's best composers — Morton Feldman. Like other mid-century American composers, Feldman achieves the classical ideal of universal appeal, inherently challenging much new music that values unnecessary obscurantism. What's not to like? — He's dissonant, but listenable; hermetic, but open; structured, but not rigid; ambitious, but not bombastic; expansive, but not monumental; serious, but not pretentious; strange, but not exotic; simple, but profound; minimal, but luxurious; static, but alive. In his own words, "it's frozen, at the same time it's vibrating." It feels incomplete, but simultaneously clear. Nietzsche’s ‘Genius of the Heart’ might describe the Feldman world — “cracked wide open, blown upon and drawn out by a spring wind, more uncertain now perhaps, more delicate, fragile, and broken, but full of hopes that have no names as yet, full of new will and flow, full of new ill will and counterflow.” His delicately patterned music, his "crippled symmetry" is very American in it's organizational clarity and expansiveness. In distinction from his European counterparts — and like almost all art in the mid-20th century — he moves more freely. Feldman often compared American and European composers and artists, for instance socially regarding their labor, noting that American artists weren't usually state-supported, institutionalized professionals, but often made their living by other means. A bohemian, but integrated in the modern workforce. A writer like Wallace Stevens comes to mind, and the modern Americanism of Kafka, who explicitly influenced Feldman. And yet, for all there is to like about Feldman, to just say, "Yes, this sounds right" and leave it at that seems insufficient, there is still something enigmatic about the meaning of his music that we enjoy puzzling over. And in many ways Feldman's music is the sound of pondering, it can be described as contemplative and seeking clarity without reconciliation, aestheticized processes of our interior spiritual cogs slowly turning, iterating. Why is Feldman so appealing? In my opinion, it is the transcendental quality of modern clarity.

Social Character

Socially, Feldman is a prototype and exemplary of the ideal artist in contemporary America, someone who seems to do their real work off the clock, in their proverbial workshop, who is not a 'professional' officially sanctioned by state institutions, but certainly no dilettante or amateur. The artistic consciousness far exceeds the institutionalized artist. This is important to understand. A Bohemian, sure, but of a particularly American type, an inventor, a critical historian, a character of American ingenuity that doesn't fit in with tradition, or at least tradition as reproduced by state ideology, academia, or philistine public opinion. It's clear where he stands, with modern abstraction as a kind of clarified beauty. There's an air of Jeffersonian Neo-Classicism, clarified by a modern American streamlining that fits it well and almost seems to be what Classical art was unconsciously pursuing. Socially, a character who is both essential but also marginal, who is an outsider in respect to traditionalist values, yet who is central to the state of musical art in some yet-to-be articulated way, often via original reflections on art and interpretations of music history. While an artist's work is not reducible to autobiography, there is still an objective social character, for instance the way Greenberg noted that Paul Klee's art was in many ways only possible due to his Swiss provincialism. An ambivalent provincialism perhaps, insofar as the provincial character was becoming an epigone, the persistence of which can preserve certain ideas and practices of art amidst its disorganization, not unlike the way Nietzsche remarked that Mozart still enigmatically speaks to us today. If Mozart is unusually clear and coherent amidst vast confusion and disintegration, the same might be said of Feldman's unique musical position in mid-century NYC — NYC is still more provincial than it presumes today, and in the mid-20th century even much more so. However, Feldman was also living in the center of the capital of the 20th century, and he had ideas of what this American artistic character meant.

I once had a wild six-hour discussion walking the streets of New York with Boulez, how he is telling me, he is really telling me but he is using Ives, “Oh, Ives, the amateur!” And I think it’s absolutely outstanding, I think it’s absolutely incredible why one would think about Ives as an amateur. No. He wrote fantastic things, like the conception of the Fourth Symphony, I’m talking about the one with the four pianos. He never changed anything, Mahler was changing things all the time. Why was he an amateur? Because he wasn’t a European? A man does all these innovations, he is an amateur; I, for years, I’m still called an amateur. I’m one of the few original people writing music, I’m an amateur! Is it only that — I never understood that John Cage is an amateur, I’m an amateur, Ives is an amateur.

But some jerk, some jerk in Budapest, in a sense, copying Bartok is a professional! I never understood this. To me the definition of professional is someone who doesn’t have a job. If you don’t have a job, in Europe you are professional.

What an incredible unmasking of the professional as someone who just copies! Needless to say, Feldman wasn't an amateur, but he certainly wasn't a professional either. Today's calculating professional minstrels are unlikely to understand. Feldman thought American composers need not be professionals in this sense, but actually might be more free specifically because they’re not professionals. This sensibility was not exclusive to Feldman, but other American artists and composers as well — e.g. Phillip Glass was still a plumber long after he was famous. Having a dayjob was not considered a sign of failure, but rather allowed for more unrestricted freedom to explore work that institutions with their own agendas don’t permit.

On the subject of the social situation of art, Feldman furnishes us with one of the clearest reflections on the (too often overdetermined) matter, a simple anecdote as obdurately real as it is theoretical …

I cannot make a relationship between music and society. I don’t know what society is because it’s alles, everything. My teacher Wolpe was a Marxist and he felt my music was too esoteric at the time. And he had his studio on a proletarian street, on Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. And at that time I just became involved, I was twenty years old, I became involved with artists in Greenwich Village, all these people. And he was on the second floor and we were looking out the window, and he said, “What about the man on the street?” At that moment he said what about the man in the street, Jackson Pollock was crossing the street. The crazy artist of my generation was crossing the street at that moment.

Amongst other readings, such an allegory implies that the alleged separation between fine artist and working class is more abstract illusion than real in our America, something today’s professional political artists would do well to understand. Feldman’s enigmatic, hermetic, and indeterminate music speaks to us infinitely more than the loser public art rackets peddling social ideology. He was acutely aware of the way American artists can actually be iconoclasts of a sort, that they might take up an indirect relationship to history and society, distinct from what he considered an almost authoritarian orientation of composers like Boulez and Stockhausen. Or perhaps a Jacobinism in music is what Feldman really meant by “authoritarian”.

If NYC was the center of the 20th century artistic world, it was specifically because Feldman thought there was a brief time — maybe “six weeks” — where no one knew what art was. It was in this crisis that great new art was made, and by implication, might still be. Yet this reflection came much later and after the moment, in a time where everybody, he thought, knew exactly what art was to a problematic and constrictive degree. This know-it-all art culture is where we are today, and in part why Feldman's enigmatic, questioningly open music speaks to us — it stands in relief. One of the reasons we love Feldman's music is this openness, an expansive searching for resonance. One almost gets the feeling that his music is simply a tapping around with tuning forks, a "philosophizing with a hammer" (Nietzsche). In my opinion he achieves this expansive feeling through a synthesis of a few compositional elements — modern reduction or a minimal "taking out" attempt at clarity; expanded scale as forming of time; and an "all-over" or "Alles zusammen!" dispersion of pitch.

The Taker-Outers

Starting with the first element of removing, jettisoning, Feldman has a clarifying reflection on Hemingway as precedent —

The point that I’m trying to make is, how do we know what to take out? I don’t like to make a distinction between Europe and America, but there is a distinction and I feel that one of the big distinctions, for example in literature, is say someone like Hemingway, he was a taker-outer. My friend, whom I like very much, Günter Grass, is not a taker-outer, he is a putter-inner, one tragedy after another, you see. Günter Grass learned nothing from Hemingway, you see. So the point is, it’s the same thing. We know what to take out. We have an instinct to take things out, maybe it’s a commercial instinct, really. Maybe it’s like writing a Madison Avenue ad.

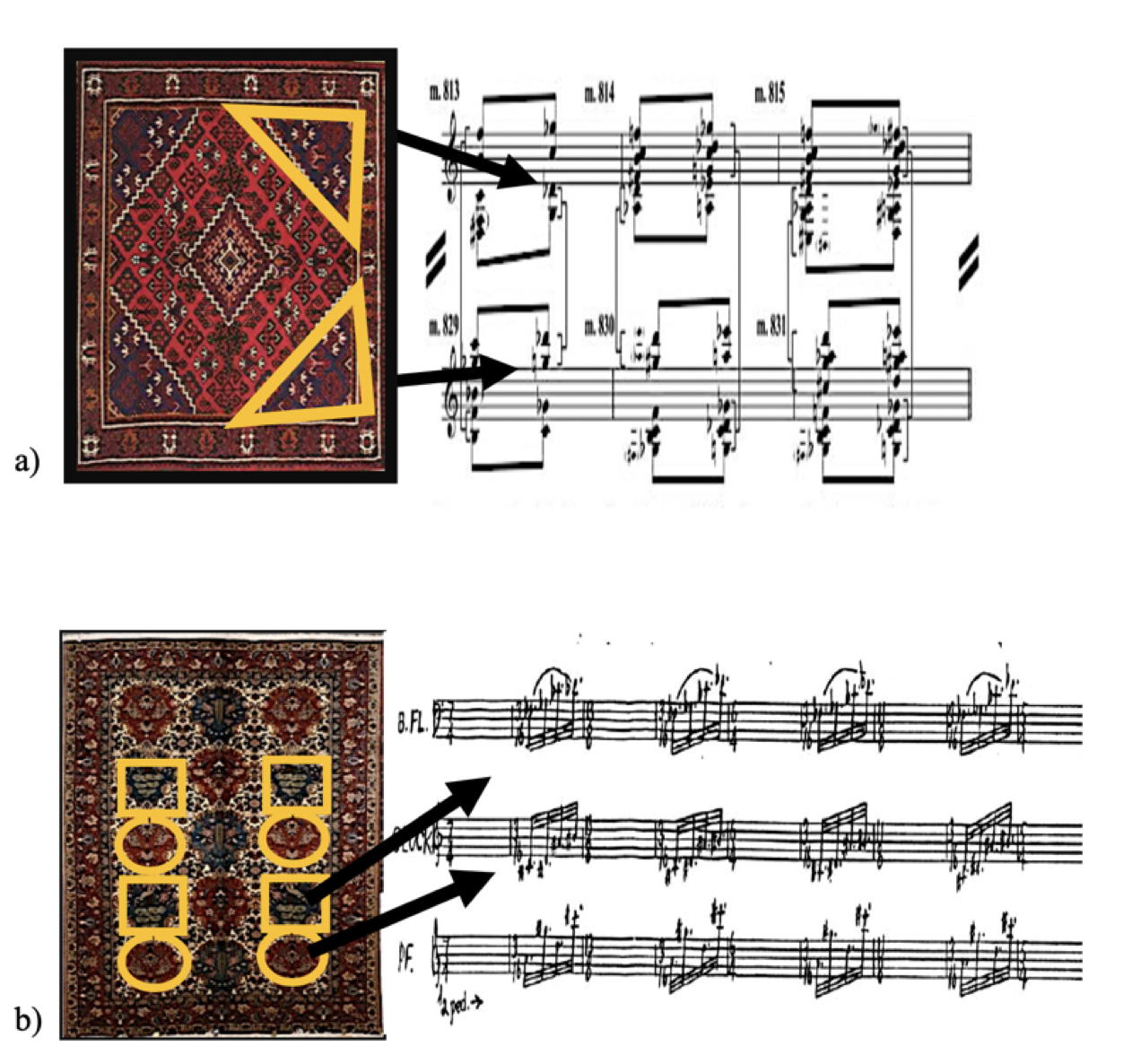

"Taking out" is typically associated with Modernism and doesn't need to be unpacked much more here. "Taking out" has a self-evident character and is the foundation of so much modern art, not just in the classical tradition, but in pop music as well, extending into the development of the abbreviated modern short story, and so on. Elsewhere, Feldman called Frank Sinatra a modern day Orpheus, and one thinks of Kanye telling Jamie Foxx to quit with all the superfluous vocal flourishes and just get to the musical point! There is an emphasis on clarity and simplicity, a jettisoning of unnecessary artistic flourishes and baggage, an attempt at lightness, but also perhaps a modern asceticism. Recently, art influencers and their conservative tendency towards Classicism have rebelled against this, fetishizing ornament explicitly as art. Feldman loved classical art — from Piero Della Francesco to oriental rugs — but importantly, he had very modern interpretations of their significance. Like many modern artists, Feldman found an affinity between older art forms and new ones, most relevant would be the patterning of oriental rugs and the patterning of modern Western music, and the inherent abstractness of Piero's masterpieces — which to Feldman shared an affinity with Webern’s integration of the horizontal and vertical — but also the very modern clarifying of art into a phenomenon of surface. Even more specifically, surface as an access point to eternity. Feldman saw in Piero an historical precedent — likely a shared affinity — of the artist who rejects the rigid and overdetermined constructive systems of his own time, forsaking perspective for eternity. Piero is to perspective as Feldman is to serialism. Overall with history, Feldman was no antiquarian, but rather a critical historian — he read his Nietzsche, quoted him often, and understood this important distinction. He did not have a passive idealization of art history, but rather a clarifying one. This means leaving certain things behind in order to understand what artworks are really about, because of course he was attuned to the perennial mystery of art. The result is a kind of eternal, suspended floating. Feldman’s music seems to create some kind of eternal environment, almost mythical in scope, with a swirling cosmic tension. There’s a meditative air, vaguely monastic, as if composed for a kind of temple that doesn’t yet exist.

Scale as Form

Morton Feldman thought of scale as a better alternative to form. He thought 'form' necessarily meant short pieces that are sculpted and manipulated in a particularly rigid way, and that the normalized 20-minute piece is a determining form, being structured a certain way and with a specific character determined by that scale.

When a work gets three-quarters in and most composers feel that’s the time they’ve got to wrap it up and be interesting, I usually go the other way. I mean, I can understand psychologically why a composer does this after three-quarters in. Many times, in my new string quartet, on the third hour I start to take away material rather than bring in, make it more interesting, and for about an hour I have a very placid world.

Feldman's ideas of scale were largely influenced by AbEx, but where time was the picture plane. Time was relevant to distance in some way for Feldman.

To me time was the distance, metaphorically, between a green light and a red light. It was like traffic, it was a control. So I always controlled the time, but I didn’t control the notes. When I started to do my free durational music, I controlled the notes but I didn’t control the time. So both these ideas meant that I had to leave something out.

Feldman had novel ideas about time and hoped to transcend the rigid measuring of time, perhaps Feldman can be called Bergsonian, a Bergson in music. This comes out in his reflection on his musical time contra Stockhausen.

He wanted it measured, he wanted time measured out, and I wanted time felt, a more subjective feeling for time, you see.

But regarding what he does on the canvas of time, Feldman compared himself to a painter —

What I picked up from painting is what every art student knows. And it’s called the picture plane. I substituted for my ears the aural plane and it’s a kind of balance but it has nothing to do with foreground and background. It has to do with, how do I keep it on the plane, from falling off, from having the sound fall on the floor. Most people have a sound that doesn’t fall on the floor by giving ita system. Harmony or twelve tone, you see. Without the system it falls on the floor. That young fellow that was improvising that stupid piece, he didn’t know that he was just falling on the floor every two minutes offhis chair. Now, this could be an element of the aural plane, where I’m trying to balance, a kind of coexistence between the chromatic field and those notes selected from the chromatic field that are not in the chromatic series. And so I’m involved like a painter, involved with gradations within the chromatic world. And the reason I do this is to have the ear make those trips. Back and forth, and it gets more and more saturated. But I work very much like a painter, insofar as ’m watching the phenomena and I’m thickening and I’m thinning and I’m working in that way and just watching what it needs. I mean, I have the skill to hear it. I don’t know what the skill is to think it, I was never involved with the skills to think it.

Radiant Dispersion

Feldman has an anecdote where he presses an art critic to consider if there are any other composers or musical works that have surface the way his music does. The critic had to concede that No, only Feldman's music seems to have surface in the way modern painting does.

I’m the only one that works that way. But it’s like Rothko, just a question of keeping that tension or that stasis. You find it in Matisse, the whole idea of stasis. That’s the word. I’m involved in stasis. It’s frozen, at the same time it’s vibrating.

There is an anecdote about Feldman teaching a young composer. At first, the student has too much bass, which is too "lugubrious". Then he comes back with too much treble, which is a modernist affectation. The student is stymied until Feldman tells him Alles zusammen! or All at once! This is a part of Feldman's 'all-over' style. Typically in tonality (Feldman's music is tonal), there is a wavelike movement amongst adjacent notes. But Feldman actually plays in many registers in a very balanced way that is intuitive and doesn't follow traditional tonal rules. But it's not just about rejecting tradition — it's rather about trying to clarify it. For instance, when pressed to reflect on Schubert, Feldman simply noted that he knew where to place things in a way where it could be heard more clearly and articulated, it seemed to "float". Interestingly, this floating quality was bound up in distance and why Feldman made music about …

the decay of each sound, and try to make its attack sourceless. The attack of a sound is not its character. Actually, what we hear is the attack and not the sound. Decay, however, this departing landscape, this expresses where the sound exists in our hearing — leaving us rather than coming toward us.

He thought "functional harmony hears for us" too much, implying a predigested art closer to what we would now call "kitsch" (no wonder classical music and pop music go so well together). In this abstracting distance Feldman is modernist, and he explicitly adhered to the idea of modernist abstraction, not to obscure, but to clarify. Regarding any historical ties to tonality, he remarked that his version of counterpoint is sound vs silence. "Silence is my substitute for counterpoint. It’s nothing against something." He follows this with a reflection on how he works "module-y", with modules that can more freely be moved around, like the way Tolstoy wrote War and Peace, and Burroughs wrote Naked Lunch. Who else would be able to connect such disparate writers! Such a far-reaching art critical association is also a reflection of his compositional consciousness, where disparate notes in an expanded chromatic field can be associated in ways traditionally unheard. Feldman's music is more constellation than wave. By his own admission, more "assemblage" than composition. Close to collage, but not quite. In some regards he’s closer to musique-concrete and its arranging of discreet sound objects than traditional tonality. However, he also thought Beethoven worked as an assembler, adding disconnected melodies whenever he felt like it (another example of his modern clarifications of traditional music). And he may actually be closer to the truth of Beethoven than any functional tonal analysis of his music. One won’t ever understand Feldman through tonal analysis, and yet, paradoxically, the music feels acutely tonal. It’s important to note that arranging music in terms of sound objects is psychoacoustically closer to how we subjectively process sound, which is perhaps why Feldman’s music sounds so natural to us.

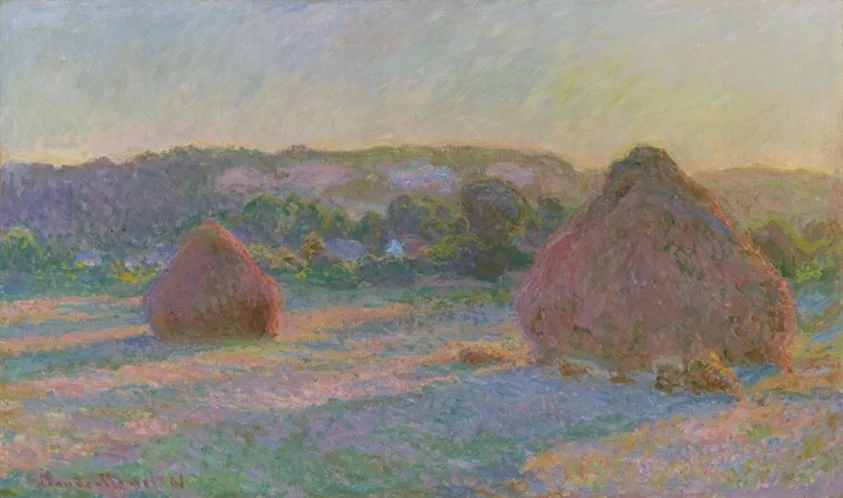

The aesthetic feeling evoked is akin to how a critic once described Robert Ryman's canvases as a radiant dispersion. On this phenomena of painters addressing light, Feldman notes that Monet was the first to really see light, and remarks that his painting of refraction has an analogue in music in the phenomena of beating. "Monet was the first one to actually look into the light. Nobody wants to look into the light. And he got the refraction, very interesting word because I think that is the same thing naturally with sounds in terms of the beating." Beating can often be heard in Feldman's radiantly chromatic, tonally dispersed music. Such refraction is what gives the music its natural beauty. But this refractive art in music is also possible via patterns. More than anyone, Feldman is the composer of patterns and repetition. It's important however that Feldman used the word iterative instead of repetitive, as iteration implies slow transformation over time. He found his analogue and inspiration in oriental rugs, which developed their iterative patterns via small-batch hand dyeing of the threads over a broad expanse, which, taken as a whole, evoke textural variation even within the same color fields. He appreciated the solitary aspect of rugmaking as well.

No discussion of Feldman would be complete without his emphasis on instrumentation and 'color', or this “microchromaticism”, a kind of post-impressionistic variating of musical hue. But there is a way in which Feldman's instruments are actually working against their complicated timbres, they sound as if stripped down, clarified, e.g. his voices and clarinets often sound like sine waves or tone generators. His instruments seem to sound like pure resonances, and so it's not really about the instruments, not at all, but rather about stripping the instruments of their complexities (often revealed in their attacks) so that they can be prepared more acutely for the ear. The openness of his music is a reflection of an open orientation to art more broadly, an orientation that was not at all reducible to the artist's hand, and far transcending it. He thought the remnants ot Ancient Greece were interesting primarily because it offered the ideal of a profoundly impersonal art, where the artist’s hand disappears. There is something very natural about Feldman's music, not because the instruments are natural, but rather because they're freed from their obscuring instrumental character and so clarified to the listening ear. Like all modernists, Feldman thought that nature could only be invented by the subjectivity of the artists.

The form this warning took was a strange resistance of the sounds themselves to taking on an instrumental identity. It was as though, having had a taste of freedom, they now wanted to be really free…

And for me, that instrumental color robs the sound of its immediacy. The instrument has become for me a stencil, the deceptive likeness of a sound. For the most part it exaggerates the sound, blurs it, makes it larger than life, gives it a meaning, an emphasis it does not have in my ear.

To think of a music without instruments is, I agree, a little premature, a little too Balzacian. But I, for one, cannot dismiss this thought.

Half a century later, is such a proposition not now mature, even overripe? This distancing aspect of Feldman sets him apart from nearly all of new music, then and now, in that most new music reinforces the character of the instrument, e.g. Lachenmann. It was Feldman (as well as Young), who was the first to really consider sound as an experiential auditory phenomena, not something to be dominated or obscured by 'system' or virtuosic musicianship. Feldman's music is listening to listening. But it's not a postmodern fetishization of listening itself. No. Rather, it's listening as a means towards clarity, as a practice of uncovering and exposing.

What we love about Feldman is his clarity. The clarified tonal fields (and his simple but profound essay reflections) stand out amidst a culture built on obscurantism in so many disparate and confusing ways.

Kierkegaard wrote a marvelous thing in Either/Or. He said he feels that when he dies, they are going to ask him only one question, when he gets up there. And the question is,“Did you make things clear?” Did you make things clear? — that is what they are going to ask him up there. In other words, in his own life, did he make things clear. How he felt, how he wrote, everything. And I am very concerned with making things clear. And maybe I’m using metaphor as a way of saying it in different ways in order to be clear, you see. Stendhal had a big sign on top of his desk, it said, “To be clear at all costs.” To be clear at all costs.

Piero della Francesca, The Nativity. 1470-75

Monet, Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer). 1890-91

Art Institute of Chicago