“Et in Arcadia ego”

This shortened version of the Introduction to the 2nd edition of Octave the Artist was first presented at the book launch event in New York City on August 9th, 2025. The 2nd Edition of Octave is available for purchase from the Adam J. Elkhadem Foundation. All proceeds from book sales go directly to support the foundation’s work.

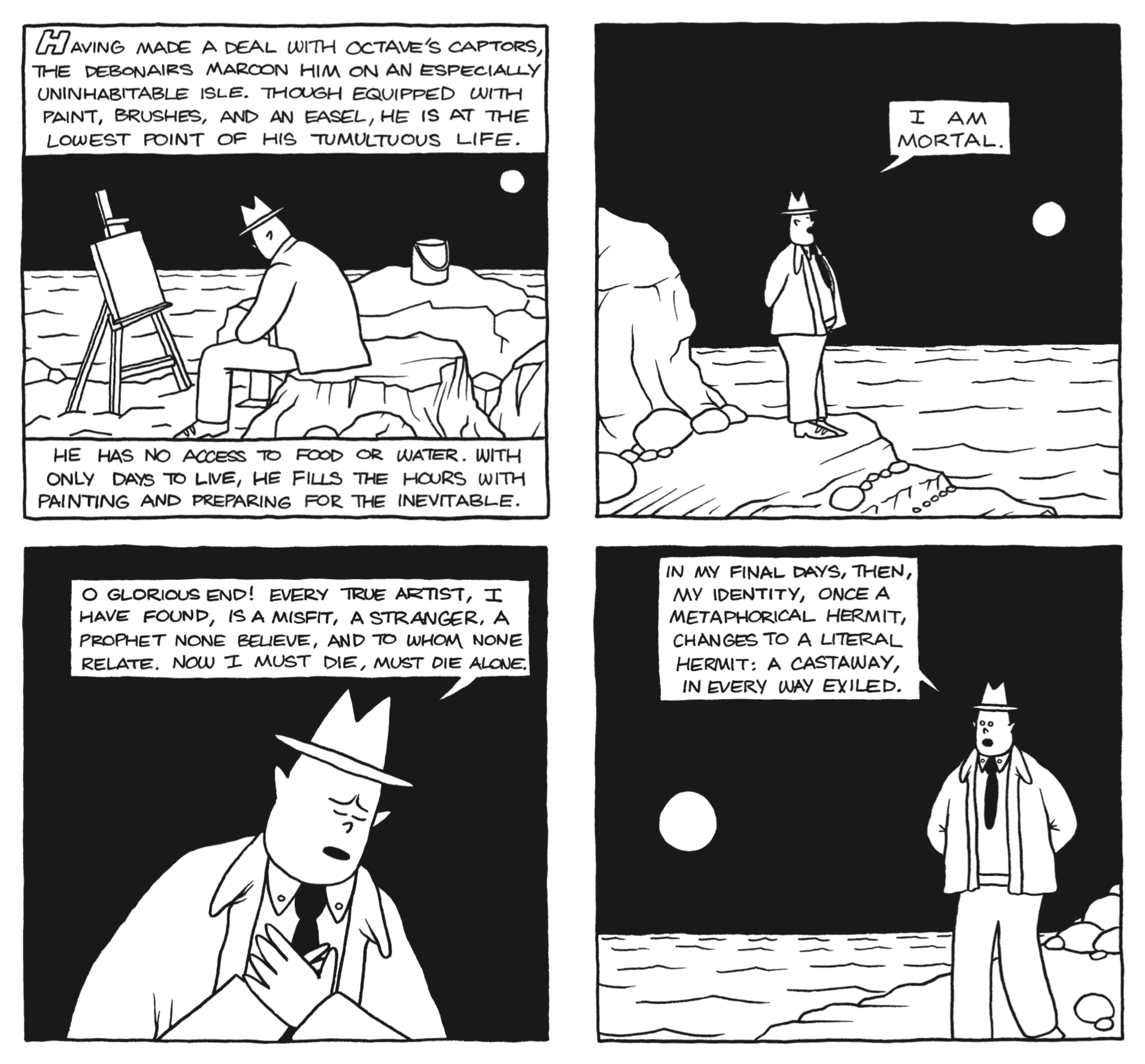

Art occupies a precarious position in society. The artist even more so. One the hand, art is officially sanctioned. It is generally taught, and ‘creativity’ and ‘self-expression’ are almost universally encouraged. The therapeutic benefits of art are studied. And the public sees art as a reconciling force. But the true artist, as Octave declaims in his eulogy on the rock, knows that he “is a misfit, a stranger, a prophet none believe, and to whom none relate.” The freedom of art is granted on the condition that it remains confined within the work of art and no further. Because art derives from play, however much developed, the public secretly associates art with childishness. In the public imagination, there are still few things more pathetic than a middle-aged artist with nothing to show for their efforts. Artists, already anxious by nature, will often find it easier to follow the tropes than try to explain how the enigmatic quality of art can become an obsession. Naïveté is a mask that allows the artist to work without having to account for their every decision. It provides cover — but at the risk of blinding those who adopt it. As Schiller perceptibly notes, “Because of their own beautiful humaneness they forget that they have to deal with a depraved world and they behave in the court of kings with an ingenuousness and innocence such as one finds only in a pastoral world.”

Adam could be this way. For most that came into contact with Adam, the infectious charm of his personality is what will stand out most in their memory. He had a singular way of inhabiting life, an intense joy and keenness for living, voraciously curious with an insatiable hunger for the grand, rare, and dramatic, as much as the fragile, tender, and sweet. And yet there was something more buried beneath this surface, which he and I recognized in one another and formed the basis of our bond. What else can I call it but an acute sensitivity to spiritual suffering? Not in a moral or religious sense but more like a predilection for the painful pleasure of whatever evades and thereby challenges one’s stable sense of reality.

Adam played the role of the earnest, romantic artist with such passionate devotion that the character of Octave is often misrecognized as his self-portrait. It is and it isn’t. Octave represents a part of him, no doubt, but in the sense of an exemplary ideal. As he writes in his preface, “I’ve always wanted to get at what an artist is, who an artist is, and what role an artist has to play in society.” In basing Octave on historical figures like Jean Renoir and Gustave Courbet, Adam sought to measure the distance between our time and that which produced our heroes. Could an artist like those we claim to esteem find a hearing today? Or would they not rather appear foolish and absurd — ridiculous to the point of grotesque? It’s true that throughout the narrative Octave is never long without his supporters, but even when he wins the adoration of the general public, can we really say that it’s because they recognize the true value of his work? Or do they not also misjudge what Octave represents, caught up in the media spectacle that brings him to prominence, at least as much as Octave’s robber baron patrons, who see him as a way to renew their cultural relevance, or the anarchist art collective that orchestrates his kidnapping in order to be able to claim another pyrrhic victory against the forces of capital?

Courbet and Renoir may have provided models for Octave, but what of Adam himself? To me, he belongs to the family of Frenhofer, that prototype of the modern artist conjured by Balzac in The Unknown Masterpiece with whom Cézanne and Picasso so strongly identified. The story of Frenhofer is thus: An old painter, respected among his peers and admired by younger artists, has been secretly at work on a painting — a nude — which to his eyes surpasses all possible beauty. But when he consents to show it to two of his peers, François Porbus, Henry IV’s court painter, and a young Nicolas Poussin, not yet established, they are unable to discern anything in the “chaos of colors, shapes, and vague shadings” on the canvas with which Frenhofer is so completely convinced had conquered illusion and created a painting more alive than the living, except for a single foot, “this fragment which had escaped from an incredible, slow, and advancing destruction . . . appearing there like the torso of some Parisian marble Venus rising out of the ruins of a city burned to ashes.” Their inability to perceive what he imagines drives Frenhofer to incinerate his work, and he dies the same night. There are parallels to Octave’s journey here, if we can transpose from Balzac’s tragedy to the comedy of Adam. Both authors depict their artists as quasi-religious fanatics, members of a cult to aesthetics, spurned by society yet committed to the ideal of art as a universal force greater than the strictures of social life and the established ways of tradition.

The Arcadian Shepherds, 1637-38. Oil on canvas, 34 1/4 x 47 1/4 in. Musée du Louvre

That Balzac’s apocryphal story is implicitly framed as a defining moment in the biography of Poussin — the same Poussin who would go on to define the classical, Apollonian ideal of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, laying the groundwork for Jacques-Louis David’s revolutionary conquest of history painting and Courbet’s later attempt at the same — should allow us to read The Arcadian Shepherds, the painting that Octave discusses with Adam, making a cameo, on a Central Park bench, as a response to Frenhofer’s Dionysian mania, an inversion of the fervid painter’s Belle noiseuse. In place of Frenhofer’s “chaos of colors, shapes, and vague shadings,” Poussin draws a clear, resplendent image of paradise bathed in ethereal golden light; and in place of the foot — “a delightful foot, a living foot!” — the shadow cast by one of the shepherds onto the face of the tomb around which they gather. Adam’s interpretation of the painting sees it as an allegorical depiction of the discovery of art, wherein the shepherds observe that their shadow, though mere substanceless image, can be fixed by tracing its silhouette and thus be made to outlast the decay of the body. Spirit conquers death through the persistence of art, whose appearance, spectral and fleeting, nonetheless has a longer duration than experience itself. The illusory nature of art serves to dispel the image of blind authority that social institutions would like to convey and which falls and collapses before the schmears of pigment-suspended oil that make up a painting will crack and wither away. The innocence of art — that it can claim nothing more than mere appearance — makes it one of the only vantage points from where the constructed nature of reality can be seen for what it is: the problem of freedom. Art reduces the world to its level, and thus makes every individual a judge of its value. Hence Dorothy unmasks the Wizard and restores Kansas to Oz. And Octave, buffeted by his odyssey and disillusioned with the fickleness of success, returns home to Houston, the place of his birth as an artist. As Walter Benjamin put it, “Origin is the goal.”

How to sum up? Octave the Artist is an allegorical bildungsroman. It tells the story of an artist coming to know the place given to him by society, how his value is estimated, and what his worth really is. He struggles against the reality he finds and tries to change it, but the power of art, he finds, is constrained to the realm of appearance. It does its work slowly, methodically acting on the imagination of those ready to receive it, who with a predisposed tendency towards dreaminess or dalliance, afflicted by a dilettantish attitude toward what most would call practical matters, possess those searching souls for whom the first potent aesthetic experience is like a religious awakening, where the light of redemption that shines from the guise of the beautiful and sublime does not flood in all at once but creeps in on the corners of thought, occupying the peripheries of consciousness, and, concentrating its forces there, bursts like a rocket in the starless night of reticent hearts, laying siege to the bulwarks of received opinion and instrumentalized reason. It is then that, as the saying goes, “images in the mind motivate the will.” For Adam, Octave was the embodiment of the radiant light of art. Octave represented his connection to the whole of life, to the totality of existence, “a driving urge that forces his hand to act and charges his spirit to some purpose close to divinity.” And now to you, his audience, Octave has been bequeathed. Let not the darkness of your days obscure the love that lurks within the slender frame of art’s illusion.

Sic semper artificibus.