Poetry: Billie Chernicoff

MUSEUM POETICA: SKÁLD

Introduction

by Michael Boughn

For years now, Billie Chernicoff has been writing an unsettled sounding, a measuring of depths through audio vibratory projection, a deep dive into the waters of, a sound proclamation. Her music resonates with a distant but immediate echo of Emily Dickinson’s fearless spiritual ordeal recorded in her broken, stuttering hymns. She follows in the tradition — well, maybe not a tradition, but a common concern — that includes H.D., William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, Gertrude Stein and their cohort, poets whose work addressed the crisis of spirit (and its attendant crisis of representation) that has increased in intensity and urgency over the last 500 years.

These poets took up the work of locating a range of knowledge and experience with their poetry that previously was the reserve of the sacred which had been skewered, flayed, dissected, bulldozed, and buried by modernity’s dis-aster, that dark star in whose light the world was transformed into a natural resource, a fact suitable for consumption as object by subjects. In the spiritual desolation that followed the breakdown of the old structures and the consequent loss of meaning, poetic language became a site of resistance, a place where prosodic provocations, uncontainable formal fecundity, could revivify the world and the sacred — or something like it in a significant way — could be returned to a zone of experience.

Chernicoff’s work circulates through this difficult engagement with language, refusing compromise or consolation, what Lyotard called the solace of good form. Referring to John Donne, but also to the poem itself, she calls it “a sermon, but [means]a play.” A play on words? This slippage between the sermon and a play is at the heart of her marvelous poetics. Sermon, out of the Latin sermonem — “common talk,” “conversation” — comes from the Indo-European root meaning “to line up,” “to join.” A sermon lines up words in a way not unlike a play in its internal dynamics. A play, though, takes writing in a different, if not unrelated, direction, itself mixing up multiple senses in a little whirlwind of meanings. For some 200 years before it became associated with a genre of writing, play was linked to “free or unimpeded movement,” so that “a play,” whatever spot it occupies in a sentence, is tied in a deep sense to the realm of children, where the unexpected move, free of purposive direction, brings delight.

The complexity of Chernicoff’s languagethinking is a joy. The presence of “husband” floods our sense of the expansive potentiality of attention with the almost invisible ambivalent plenitude of our domestic reality. “The meal in the firkin; the milk in the pan; the ballad in the street; the news of the boat; the glance of the eye; the form and gait of the body,” as Emerson so eloquently put it in his claim for the ultimate significance of the ordinary and common, ending, of course, with the body. The husband, intimately familiar, but always more and other, the body next to you in your most exposed moments, the sign of a trust that is beyond question, but always in question, given your fatally exposed fragility, that precarious balance, is the figure of our new condition, our crippled spiritual beauty. Our writing.

The sounding of Chernicoff’s poems is utterly common and at the same time rooted in a mythic intuition that in-forms every syllable. The precision of the movement of the phonemes locates us in relation to the fact of the infinitesimal scratch, the resistance of horsehair on stretched gut, that composes the magnificence of Bach’s “Partita.” This is part of what Robert Kelly refers to as the “hesitant, graceful music” that Chernicoff converts “into a visual apprehension of physical movement.”

Tell me your say,

its etymological silk

to finger, a sea

called sea,

a sail called sail,

your thou art,

or other name for God,

I pray you too catch a wave.

Michel Deguy, in A Man of Little Faith, his discussion of our condition of loss, appeals to transcendence as opposed to the transcendent:

There is no transcendent, but there is transcendence; movement; being carried away; movement, momentum, élan in French, ormê in Longinus: the invention of an overlook, of the sheer and steep (upsos), of the point-from-which. This is what gives meaning, makes meaning, in the sense of a sense.

This is another way of speaking to our entanglement with time, that supreme mystery, which itself is entangled with that other mystery, which Chernicoff has as bone’s language. As with Dickinson, she repeatedly comes back to the question What else is there? once Beyond is lost. Her answer is an entanglement of times and minds that move together in an exquisite dance, a dance that limns a world of luminous finitude. What else is there? is not a cry of despair, but a lucky opening into our precious connections, rich networks, rhizomatic entanglements, and an injunction to pay attention.

Beautiful and mysterious in the extreme, her poems are messages from the borderline offered as testimony to the thrilling precariousness of our spiritual adventure.

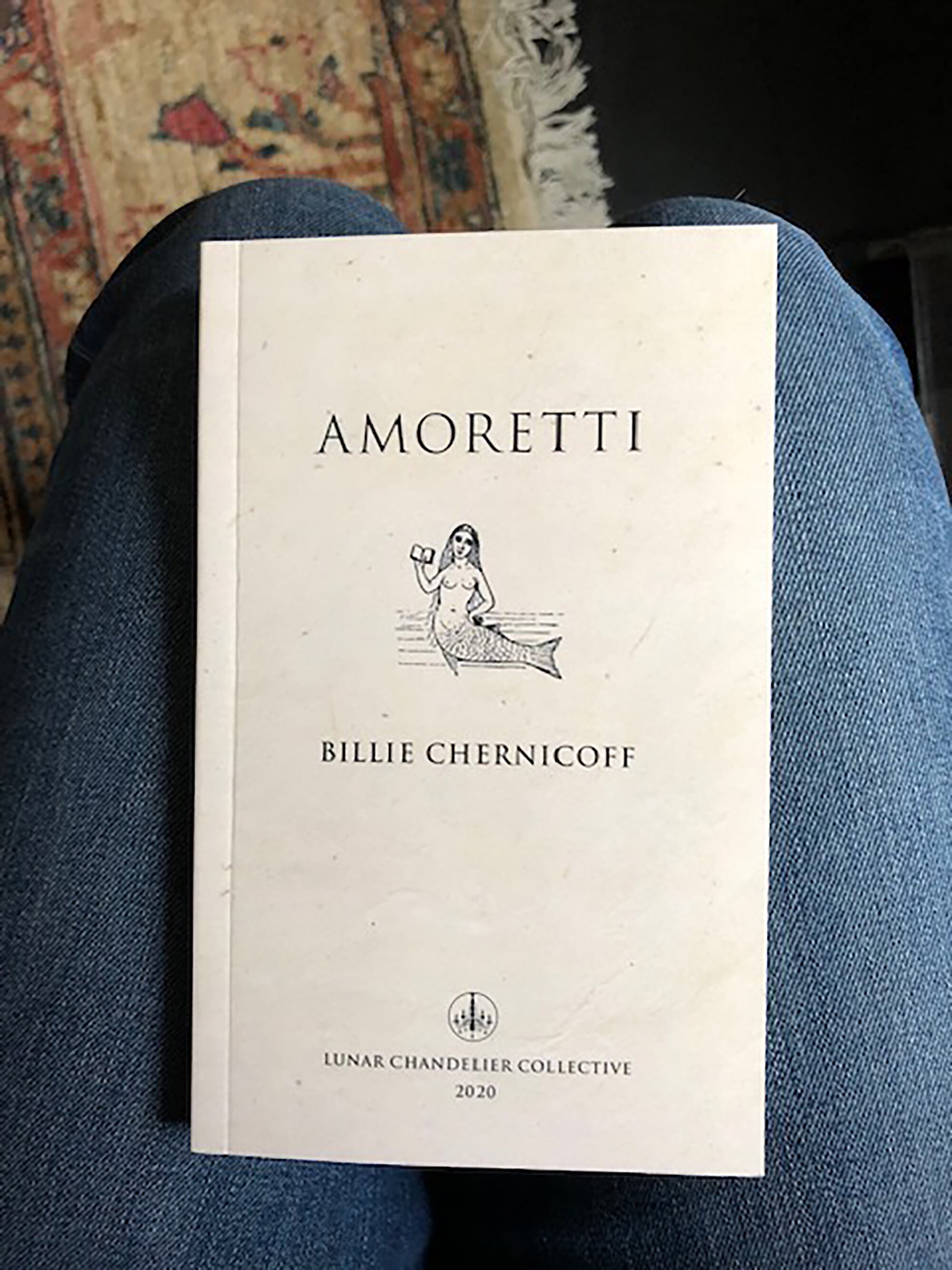

Billie Chernicoff is the author of several books of poetry, most recently Amoretti (Lunar Chandelier Collective), as well as The Red Dress (Dr. Cicero Books), Bronze, and Waters Of (Lunar Chandelier Collective). Chapbooks of her work have been published by Metambesen and Dispatches from the Poetry Wars, and one called Pensées was recently published by The Swan, at the University of Pennsylvania. Chernicoff was co-editor with Tamas Panitz of The Doris, a magazine of new writing and translation, from 2015 to 2020. She describes A Sail on Lake St. Clair, composed in October, 2020, as “a suite of poems linked by their obsessions: dreams, lies, art, water, god, love, beauty, touch, things and the language we use to tell each other about them.” //

Nathlie Provosty, Palazzo Gallery, Brescia, Italy. Installation.

The poems were not written to the paintings, and the paintings do not illustrate the poems.

I imagine wandering through a museum, lost in Provosty’s images, the poem as a voice overheard — a few words, a pause.

Nathlie Provosty came to mind at once when Caesura asked me to find images to publish alongside A Sail on Lake St. Clair. Her sensual, mysterious paintings are portals, dreams, deities, a bodying forth of the spiritual realities of letters and numbers, of geometry.

Figures multiply, break and reassemble, elude — an intensely physical metaphysics, formal as Byzantine icons, fluent as water, eloquent as silence — a silence full of holy presence.

—Billie Chernicoff

A Sail on

Lake St. Clair

Billie Chernicoff

Tell all the Truth, but tell it slant —

Emily Dickinson

...in the unsayable, where the lie takes refuge,

that dream caught in the act, sole love of humans.

Céline

Council, Untitled (18-27). Watercolor on paper, two sheets, each 8 1/4 x 5 7/8 in., 2018.

1. magnetic field

Bring me your ruse, a rose

a portion of meat, your news,

a more charismatic water.

Tell me your say,

its etymological silk

to finger, a sea

called sea,

a sail called sail,

your thou art,

or other name for God,

I pray you too catch a wave.

Say me the song this word

once was, un songe,

un mensonge,

a dream caught out.

Mesmerize me,

things being

what they are (stars)

our hands moving over, among.

2. linguality

The way your mouth

says Owl, a kiss

of the lips,

apart as we are,

we saints

who dream only of kissing.

Not that I mind

kissing your antlers,

or writing with

this flaming pencil

whatever falls from the sky,

Owl, or brushy, velvety

things so inclined.

Recto Verso (Untitled, 13-34), (recto), Gouache and walnut ink on Losin laid paper, 5 3/4 x 8 1/8 in., 2013.

3. fontanel

Her yes moves through her

sways her, loses her

balance, her book

falls open,

a drift of pollen.

Her yes possesses

in the midst of the crisis,

a no, an apartness,

she is, and isn’t

her instrument, sextant

or lute, like anyone,

free to stay.

Our lady hails her life

and yours,

conveying to you

her shakti, her juju

conceived of tenderness.

Re-animate the word

lovely for me,

that I may say

how lovely

she is in her confidence.

She bows

and the alphabet

hovers,

in the glory

over her head,

every letter, at the ready.

VOYEUR (19-07 e). Watercolor, gouache, shellac with pigment, and graphite on wove collaged paper, 12 x 9 in., 2018.

4. dear reader

The one who isn’t ashamed

of being or doesn’t mind

being touched, or touching

or doesn’t mind being

ashamed of touching

like water, for its pleasure,

yet not indifferently,

caressing even a pebble,

the one who touches

an oak with his forehead,

or reads a leaf

with her fingertip,

or a door with his knee

or the air with her mouth,

touching things with her voice,

so they can breathe

and say what they know,

and what she knows.

5. I draw a card

You again, fish!

Balancing on your head

this time, smiling,

a rose in your mouth,

teacup perched

on your tail as if

such friendly Christfulness

were ordinary,

a good, cheerful cup,

though I know you worry

for our sake

and yours too, a little.

Council, Untitled (18-30). Watercolor on paper, two sheets, each 8 1/4 x 5 7/8 in., 2018.

6. the news

Urgent to find

a complicit translation,

a dream,

not mirroring

rather attuning to,

or a tuning of,

chaos,

a catastrophe

we somehow disarm,

dismantle, rework

the music of,

otherworldly,

oneiric intervals,

is this sound cloud

or tear gas

our own perfume?

Flowering monstrosities

someone says,

Baudelaire, I guess,

meaning us, and we weep

as we should

we all weep at last.

7. the Sienghenberg

A landscape,

even a face, depends

on having been

dreamed,

dream comes first.

Frederic Church

would’ve known that,

casting a rectangle

over a meadow,

whitest linen,

a picnic blanket,

I realize, big enough

for a wedding party,

though I’m the only one here.

No doubt, the others

will soon arrive,

carried over

the winding carriage roads

of the high place, Eden,

our Olana,

by milk-white donkeys

imported from Syria,

one of the pleasures devised

by my husband, Frederic,

if this be his dream

and I am Isabel.

Isabel,

I lecture myself,

there’s nothing to do

but lie down

and wait,

you may as well be dreaming.

Council, Untitled (19-04). Watercolor on paper, two sheets, each 8 1/4 x 5 7/8 in., 2019.

I vanish into an owl’s call,

“Who cooks for you,

Who cooks for you all?”

The owl vanishes

into the hemlocks,

the hemlocks into history,

snow drifts over me,

silence closes my eyes.

I dream leopards rove

over Persian tiles,

I dream we unbutton

our long, black dresses,

wear nothing

under Bedouin linen,

tulip-like turbans

from Isfahan, a theft,

a pseudo-Levant

of our own invention,

but what makes us dream

our clothes or orchards

or language belong to us?

Fred dreams he’s done

with canvas and likenesses,

turns his hand

to roots and branches,

pale green lichen

feeding on granite,

the thick duff

under the hemlocks.

Fixated on shale,

its thousands of layers

of information,

he listens to leaves

and loves his well-house,

his apples and bees,

the weightless red eft

on his palm.

He considers the lake

trembling

under a breeze —

after so much sky,

after Egypt,

and all the lurid,

sublime, inexpressible

distances, finds

he’s moved by a drop

at the edge of a leaf,

the small wetness of his wife —

what he knows by touch,

or being touched,

most secret practice

of magic, both

willful and accidental.

Untitled (16-57). W25 x 27 5/8 inches, 2016-2019.

8. tryst

Among weird things,

a matted hump of fur,

a tiny black shiny carapace,

blooms of orangey lichen

along dead wood, and blooms

of pale green lichen

on living stone, nowhere

to hide ourselves

and no reason to,

I feel small and beautiful,

like a giant at home,

squatting among

the almost bare trees,

my breath added to the

breath of the woods,

the healthful, infectious

sum of things

and me, peeing neatly

between my boots,

my water seeping down

over days and weeks

to a narrow perhaps vernal

stream, just water again,

no one’s again.

My friend said a woman

should pee in every story,

and another said

everything will be alright,

is alright now.

I hear the sound of my water

hitting the thick leaves,

I hear a bird calling, and you answering,

you, my lookout, looking modestly away.

Council, Untitled (17-13). Watercolor, wax, and dry pigment on paper, 8 1/4 x 5 7/8 in., 2017.

9. a sail

Under such blue,

mild as Mary’s,

what harm

could befall

a falling

child falling

into a lake

or cradle,

a sunlit palace —

but what makes us dream

of drowning in heaven,

what makes us sail

for Jerusalem?

The sail!

triangular revelation

of holy spirit,

a breathing

presence,

bright shield,

proud mother.

10. vita nuova

a sail is a remembering, a haunting of an occurrence that haunts me. We lived in Detroit, not far from the river and Lake St. Clair. We moved from that place when I was five, so I’m younger than five, before my brothers were born. We were sailing on a summer afternoon, a happy company, talking and laughing on deck, and I somehow fell over the side, floating on my back for a few moments before beginning to descend very slowly through the water.

I could hear the grownups’ chatter and laughter, and it was lulling, magically so, like the quiet rise and fall of my parents’ voices from another room, when I was tucked in bed, safe in their nearness, and free, exquisitely free, in my aloneness, and I saw the sail above me, full, billowing, as I lay on my back in the water, the sail, dazzling white, and the sky, a mild, serene blue.

There was no fear at all, sounds growing fainter, barely a murmur, sail still bright but indistinct, a radiance above me, the water now over me a transparent sunlit green, the cooler water below holding me, the lake embracing me, a sensual, even erotic, pleasure, that was also deeply comforting, an experience of absolute trust and bliss.

I forgot the episode for many years, and no one ever spoke of it. Perhaps the adults were ashamed of having allowed me to fall into the lake. At twelve, with more a prefiguring of consciousness than real awareness, for I was still quite vague and drifted from one moment to the next without much thought or intention, I asked my mother about that day. What had happened? How was I saved? Why did we never mention it?

She was brief, dismissive, telling me only once, firmly, that the fall had never happened. I had not fallen into Lake St. Clair, or any other lake, and almost drowned, we had never known anyone with a sailboat, had never been sailing at all. It was only a dream, she said, and she sounded as ashamed of my dream as she might have been of letting me drown.

And so it became the first dream, the first, sacramental, lie, or secret memory of death, or birth or falling in love, the dream from which I’ve never been rescued.

Council, Untitled (16-13). Watercolor on paper, 8 1/4 x 5 7/8 inches (21 x 15 cm), 2016.

11. the blues

Eating lilacs, slightly bitter,

borage, blue stars

tasting of cucumber,

blue hyssop,

tasting of licorice —

a quest

for a homeopathic blue,

hard to find

as someone calling

before you were anyone,

only the curious body

you still are,

always reading, caught up

in the blueness you

teach yourself to breathe.

Haint or haunt blue,

haunting blue,

blue from indigo,

blue enslaved,

unspeakable blue,

ancestral blue alchemy,

blue unfettered,

forgiven, redeemed,

blue in tears you teach

door to door, blue door,

blue shutters, porch-ceiling blue.

You ghosts, you devils who ride us, keep out of this.

You others, resist, stay in this hidden blue realm

for awhile with us, dream, if you want.

Untitled (14-12). Watercolor on paper, 10 1/2 x 12 inches, 2014.

12. as it is in heaven

Since March we’ve touched

only each other, marrying

over and over.

We begin again like verses

and mornings, ashamed almost

of our luck, the luxe of it.

Sometimes a dream

leads one or the other

into the day, a cloud

or a bird, a well or a mill,

a kiss or a crime or just a feeling

of sadness or menace

left over from having been lost

in a crazy once familiar city,

something to shake off, dispel,

or the glisten

of a recurring lake,

the illusion of distance

and destination,

thirst, lust,

a place to begin.

We let each other be

or not, a little tea

slops over the rim

of your cup or mine

and the other

takes it personally.

We forget to kiss then kiss,

we marry for love,

agreeing to the sky also,

and the cracked cup,

ruined carpet,

pregnant moon,

the postman and the apple tree,

the fox in the yard, the ringing phone,

the table, the bread, the salt.

13. resembling the series of ancestral types from which it

has descended, a recapitulation

In doubt, say thou

to a lie, a dream

caught out,

a trembling lake

alert as a hare, lost

in the wild of your house.

Solve for X or an owl

with a mouthful

of roses,

or ashes of roses,

reverse the order

of operations, first

forgive me

and all fall down.

Sail or null,

no one there,

or here

where you listen

for friends or demons,

finding only a moon

to see you home,

a dark stone

held up to the light.

And that darkness

you hold

between your lips

is only a word

among others by morning

you find you’re able to speak.

Recto Verso (Untitled, 13-37), (recto), Gouache and walnut ink on Losin laid paper, 5 3/4 x 8 1/8 in., 2013.

Things want only

to vanish,

be gone, unmarry

like fox-wives

and selkies, go home

to their woods,

real names

and blue mothers.

Unsayable flowers

from flowerville,

dreams, not in

but of abeyance,

intimate, eloquent,

fearless ephemera,

brief as days,

chanteuses

and troubadours,

images, icons

prefiguring miracles,

memories, lies,

those sole loves

of humans,

petals of vast cosmologies.

O, of, dear

sleeve of a coat,

trees bare of leaves,

a city of silences,

refuge of lies,

dreams

of an evening,

o lovely of

east of a lake,

a mystery

truthful as anyone.

Nathlie Provosty (b. Cincinnati, OH 1981) lives and works in New York City. Paintings have been recently exhibited at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (2020), the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York (2020), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2019), and the Kunsthall Stavanger, Norway (2018); her first one-person institutional exhibition was held at the Risorgimento Museum in Turin, Italy (2018-2019). The artist is represented in the collections of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art, among numerous others. In December 2020 Hassla will publish a new image/poetry book of the artist with poet Anne Waldman; the collaboration coordinates with a solo exhibition at A Palazzo Gallery in Brescia, Italy. The book is titled All Rainbows in a Brainstem / That We Be So Contained, and features work made during the Covid-19 pandemic. More information is available on her website.

A Skáld’s Gallery

Billie Chernicoff

1. I was born in Detroit and grew up in the woods of upstate New York, and in books, especially fairy tales.

2. Strangely, this is the only photo I can find from my time at Bard College, where I studied with the poet Robert Kelly. I learned to garden in this walled garden at Ward Manor, and still garden there sometimes in my dreams.

3. I don’t remember where this photo was taken or by whom, or what I was reading. With a magnifying glass I can make out the word SALT in big letters on the right hand page.

4. The composer Larry Chernicoff and me on our wedding day.

5. After a while we were surprised by a daughter, Lydia.

6. Violinist Lydia Chernicoff (left) — Charleston, South Carolina, 2019.

7. After many years as a civilian, living in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts, writing very little and publishing nothing, I returned to the wilds of poetry. In 2014, I read at Bard with the poet Tamas Panitz. We became friends and co-edited the poetry magazine The Doris, for five years.

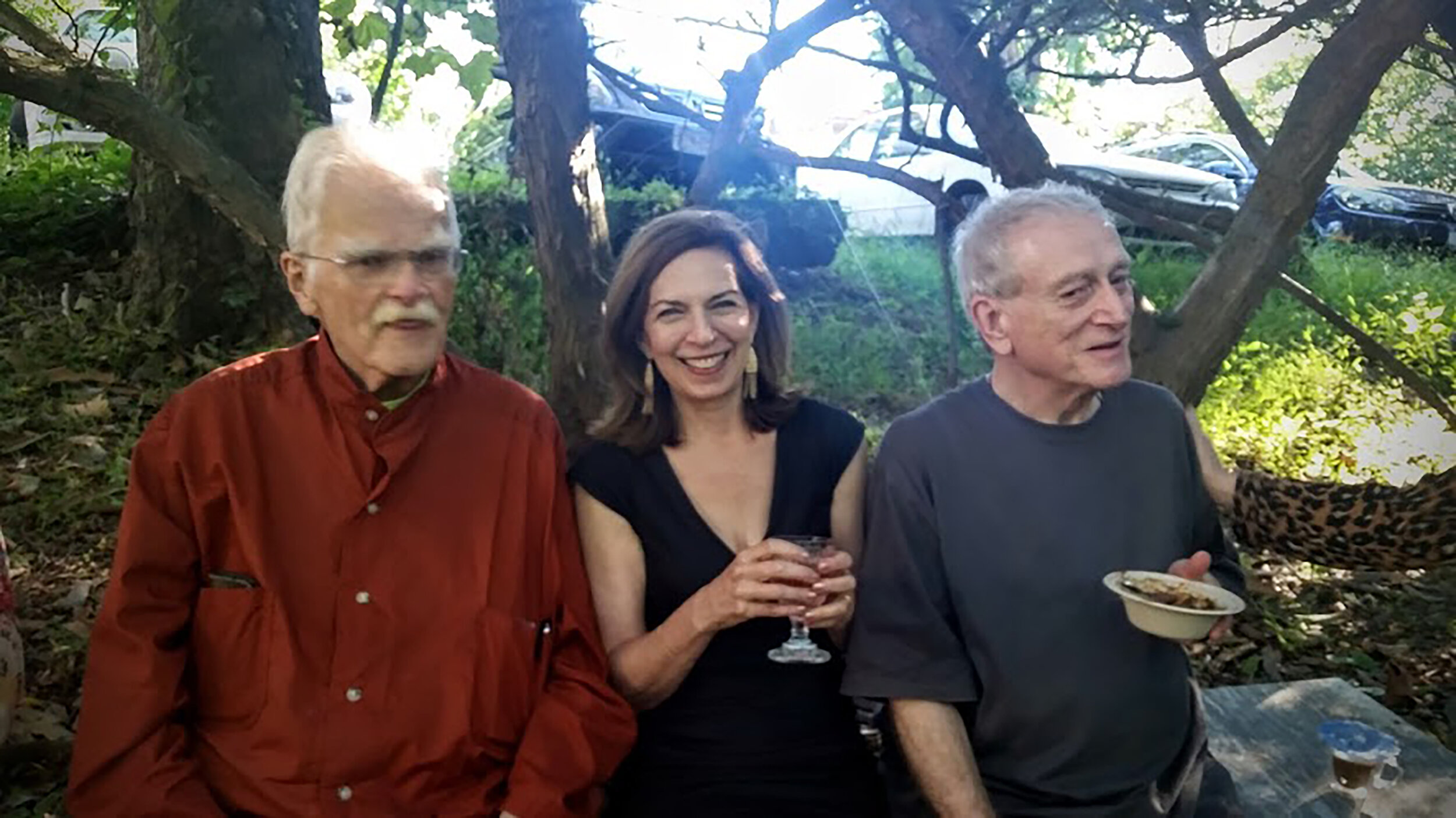

8. With poets Robert Kelly and Michael Ives after Robert's annual November reading at Bard Hall, this one in 2015. Novelist Carey Harrison, editor

of the wonderful press Dr. Cicero Books, took the photo. Michael and I both had books published by Dr. Cicero that year.

9. With Robert Kelly and George Quasha at a party George and Susan Quasha hosted for Kimberly Lyons and Vyt Bakaitis, who were moving to Chicago.

10. That same afternoon.....poets Tamas Panitz, Charles Stein, Lynn Behrendt, Robert Kelly, and translator Charlotte Mandell (center), writers who welcomed me back to poetry and the Hudson Valley.....

11. .....and poets Kim Lyons and Vyt Bakaitis, guests of honor.

12. I met Michael Boughn when we were invited by David Giannini to read together in Lee, Massachusetts.

13. I've worked as a waitress, switchboard operator, printer, gardener, flower arranger, and yoga teacher. This photo was taken last winter — I was teaching yoga in Tannersville, New York, in the shadow of Hunter Mountain.

14. At Olana, 19th century painter Frederic Church's paradise, with pianists Xiaohui Yang and Ronaldo Rolim. Larry and I live directly west across the Hudson River in Catskill, NY, a couple of blocks from the house of poet and painter Thomas Cole, who was Church's teacher.

15. Reading new work on the front porch, October, 2020, with Catskill neighbors, poet Lila Dunlap, and Tamas Panitz, King of Hungary.

16. This fox visits our backyard from time to time.

17. Published in 2020 by Lunar Chandelier Collective, where many exciting books of poetry may be found.