On The Poetic Works of John Devlin, Part II

Read Part I here.

Enigma of the Piano (1991-94)

As with Part I of this article, my aim is largely to make Devlin’s work available, so I’ll be quoting him extensively in the following pages.

In my correspondence with him, Devlin has written of the latter two books of his Triptych Canadensis: “[T]he remaining two volumes [The Ghost on the Mezzanine; and Enigma of the Piano] are each governed by two different overarching themes, or algorithms: everywhere present, nowhere seen.”

Enigma of the Piano is a long poem of 22 pages, 22 lines per page, with two stanzas per page. Each stanza is in a free verse that takes pleasure in what feels like Heroic Couplets (rhymed couplets in iambic pentameter) and for the most part indulges in the rhythm of that form. As with his Painting on a Curved Surface (1983-84), Devlin’s ‘narrative’ is inherently mystical in that it does not appear to follow a predetermined plan. Enigma of the Piano does, however, have a projected underlying structure. In an email from Devlin to the poet Lila Dunlap, he writes:

The code that holds the whole poem together (perhaps?) is a musical, or rather a pianistic ratio. It generates the number of lines in each page (22) and the number of pages (also 22). I’m not going to tell you what it is, but rather just let the idea hang in the air. The whole poem is variations on this pianistic theme.

While the length and line count of Enigma of the Piano are a projection of this code, to the mystical ‘narrative’ of this book is added another mysticism: the intensity of Devlin’s rhythm. That which carries the poem also draws words in from the poem-to-be, like water from a well.

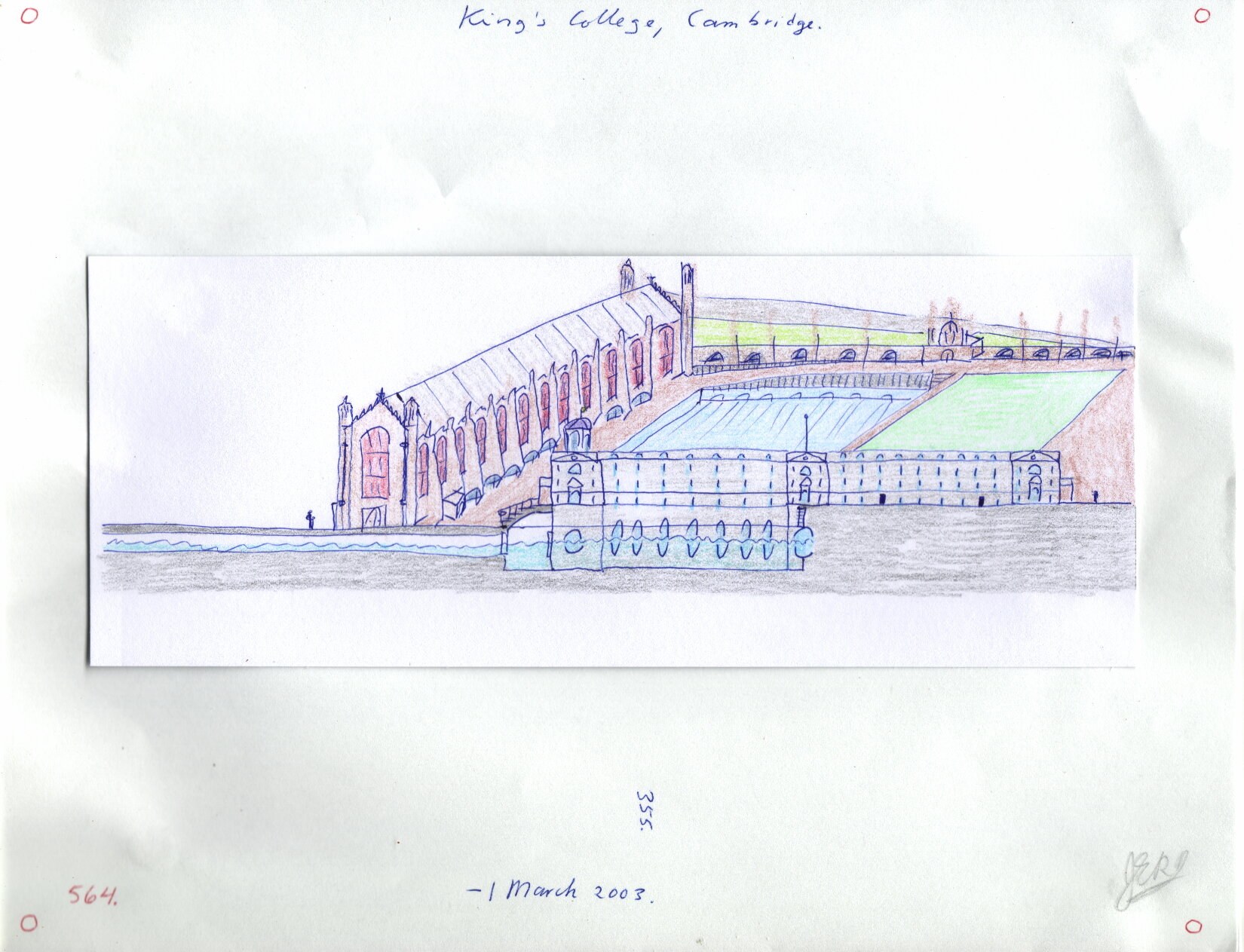

John Devlin, Study of King’s College, Cambridge, 2003, Mixed media on paper, 21.6 × 28 cm. Collection of Diana Devlin.

In Troy I died: I will rise again to breathe a fresher bloom of breath

on these ancient streets; in this Asian spring I will exhale a fresher bloom

of breath so that these bones of warriors shall live. Rising: joint

of bone and tissue joining bone and bone, a whole army resting on these shores

of Asia Minor where the anemones and almond trees bloom, recalling Granta Water

or Grand Pré, when Margaret’s brother died in the Great War. To be seen

again in a renewed past, no laws of physick broken, no bones broken

or tissue severed but to exult in being alive again: to walk on this hallowed ground

around a magic ring of holly bushes, here in Nova Scotia, almost an island

but jutting out into a cold North Atlantic, sometimes wafted by the zephyrs of

the Gulf Stream. Flowers expand under such a sky, caressed by a balmy, moist

flow in off the water, and the poppy and rose shall be one. Under mild western

skies, under mild western eyes that see the Garden where the Rose and the Hart

will be one. The music coming in off the calm, flat waters does not jangle my

nerves, but offers a soothing balm to a soul lost in a forest searching and

searching so many long years, and not even knowing what it was to be found.

Not to find but to be found: when expression was eventually vouchsafed in

the harsh spruce woods. The lotus floats counter to the climatic flow to

rude Nova Scotian shores. John, my brother, died in the War, buried in Italy

Now do not say I am sad or grieving, for I know that my Redeemer liveth

Now do not say I am deceived in my longings, for I am glad to be here

This place my brother, John, died to save.

The self-discovering mystical quality of rhythmic verse is described in the second stanza and here presented in relation to explicitly Christian concerns.

“The music coming in off the calm, flat waters does not jangle my / nerves, but offers a soothing balm to a soul lost in a forest searching and / searching so many long years, and not even knowing what it was to be found. […] I know that my Redeemer liveth[…].”

It strikes me that this Redeemer is peculiarly legitimate because it is not a closed concept or mental bind but one that comes and goes, nascent in activity, neither dogmatic nor copyrighted.

Something like this Redeemer is illustrated in the frontispiece, dated 29 January 2015 –– part of Devlin’s “Faint Man” series, which is a serial work featuring this same de-personified and partially materialized being in various liminal scenes. The Faint Man is a partial outline, both possible & immanent: that same dialectic in which I so often find Christ-like entities in my own mentation. As for the precise identities of the Faint Man, the Redeemer, or even the John of the poem, they seem to me of uncertain value in themselves, because, with a fascinating and charming humility, these characters are players in the imagination of the reader –– and are the reader, much as the Franciscan Meditations on the Stations of the Cross involve envisioning oneself as Christ in order to experience his sufferings. The people of the poem matter in that they are aspects of human experience, entities, touched with Devlin’s loss, longing, and hopes. They become universalized momentarily in their transience. In another time, we might have called them angels.

The Greek apokalypsis (as in The Apocalypse of John) means “unveiling.” Parts of this poem are strongly reminiscent of the tone, and also the rhythm, of The Apocalypse of John, for example:

John Devlin, Untitled, 2015, India ink and graphite on paper, 21.6 × 28 cm. Collection the artist.

And I was pounding at the gates of paradise for a long time, and

I became weary for the gates would not open, and I had not the key. So

I lay down for the space of an hour or so with a Rock for my pillow.

And when I awoke Mars had set in the west and the waning Moon had risen

and cast a wan glow upon the locked gates. And I looked more closely

and noticed with a dull eye that a panel in the gates had slid open

and revealed a grille behind which was a sign. And upon this sign were written

in green letters the words: ‘You are the god of love, so why do you not love me?’

After this I heard thunder, and what the thunder said was: THE COLLEGE IS

CLOSED. I turned to the south, and noticed a curiously-wrought table with

three legs; and upon the table was a golden bowl. I lifted it up in my

hands and it fell apart in three pieces. And in a grotto within the bowl

fell into my lap a silver key tied with a green ribbon. So I took the key and

fitted it into the lock of the gates of paradise. And the gates opened and

creaked upon their hinges as if they had never opened in a long time. Then

there was revealed to me a vista of a great sooty city, in ruins, of costly

palaces which had burned. And I wept, for only owls and dragons could live

there, and I ran out through the gates with my hands covering my eyes

for I dreaded the loss of so great a city and its inhabitants and cattle.

Then I heard the thunder for a third time, and what the thunder said was:

Seek ye the worm in the telescope. This was a very great riddle to me.

So I wept and wept because the riddle was so great.

I want to be careful not to overstate Devlin’s prophetic lineage, since he states no prophetic intention (in the manner of, say, Blake, Austin Osman Spare, or George Barker). I think it best here simply to draw a comparison to the great Sage of Patmos, with the writers just mentioned serving as handmaidens.

The transient value of information in this poem — the people, places, and things — can be understood within the history of Christian aesthetics, rather than as being merely symptomatic of modern poetry and nothing else.

The re-imagining of Christianity among its livelier adherents is as vital as any secular “poetics.”

Devlin calls for a radical re-imagining of — or reconnection to — Christianity. Enigma of the Piano performs that re-imagining in its transient moments, memories, friends, world-ages, or civilizations with specific cultural referents, or astrological events, among a variety of other nodes of energetic refinement.

John Devlin, Untitled, 2018, India ink on paper, 21.6 x 28 cm. Collection the artist.

After the titanium oxide ore Lunar Torus fell to Earth on Mount Erebus,

it was moved in five pieces to Oxford where it was put on display

under the dome of the Radcliffe Camera in a glass coffin prelude to

an afternoon Orpheus with his narrow, flat hips Let me see

Orpheus with his narrow, flat hips Under the dripping gum trees

After he left Dorothea Philandros crossed St Mary’s Bay and founded there

a holy city: Philopolis Royal, which became a great haunt for

all the sycophantic dukes who constantly hounded Pasta for her arias.

I think Dorothea refused to imitate Dido, and lived to a great age.The King is melancholie againe and reclines upon his couch with his

face towards the wall. He has a wound in the thigh which will not heal.

Parsifal and Philandros have vine-leaves in their hair. The post upon

which the central fan-vault of the chapter-house rests passes through the

Torus. The Torus, in the proportions of its four elements, governs

Philopolis Royal from the very centre, as a legendary stone under the seat of

the throne of the kings of Cornwall did in former times. But the former times are

passed and the minor poets of a new Silver Age cram the King’s Library.

Wanly wanders the Queen down the King’s Gallery on a rainy morning. Under

the gilded frescoes rotates the Greek Venus upon her plinth. The Queen,

like Eva, is sightless, like the Greek nude which gazes with sightless eyes

this rainy morning. The masons have not yet finished the vaults of the new

banqueting-hall. Hard by Clare College the new Hall, like the New Age, is rising.

Clearly, Devlin should be considered not just as a poet but as a radical Christian poet within the history of Christian thought. However, I will forgo drawing a more elaborate timeline of such a history in favor of a discussion of the Christian aesthetics of Devlin’s verse.

The poet Robert Duncan published his essay “The Poetic Vocation: A Study of St.-John Perse,” in the November 1961 issue of Jubilee: A Magazine for the Church and Her People. A quote from that essay will be illuminating here. Duncan compares and contrasts the aesthetics of Perse to Dante; this will neatly identify both the particle and the wave, so to speak, of Devlin’s aesthetics.

Duncan writes:

[…] Dante’s powers as a poet are greater, larger, than Perse’s, for Dante can work with particulars, bringing to his imagination the material of actual event which Perse does not encompass. It is part of the lure and sweep of Perse’s dream that the objective correlative (the existence of the things of the poem in the realm of empiric and pragmatic reality) plays no part. This coinherence of the actual and the fictive or romantic in the real, the guarantee that the actual gives to the real, that is so important in American poetry after Pound, Williams, and H.D., does not operate in Amers or Chronique. […]

The feel of the actuality in the real of The Divine Comedy is immediate to the things of the poem – we come to believe that Dante really had this dream to which the poem relates. […] [w]e come to believe that these voices really speak in the poem.

The Divine Comedy arises along the lines of a structure of particulars assigned to their places. An absolute segregation or divorce or alienation separates the damned and the blessed. Dante’s universe presents an irrevocable scheme. It is the reality of the Christian dogma, where authority, if it be catholic – concerned with the whole – must condemn most of human experience to eternal damnation. Adultery is a crime in the world of the Divine Comedy where all bounds must be defended[…].

Perse’s “currents of spiritual energy in the world” are the courses of the daemonic, where Christian concern must divorce the angelic from the satanic. The whole tendency of Christian thought has been further to divide the real from the unreal along this line, and gradually the whole daemonic world – angels as well as devils – has seemed unreal. But for Perse, the spiritual, the Divine, the real, are undivided: “One same wave throughout the world, some same wave throughout the city,” the Lovers cry in Amers. […] The Lovers of Amers do not worship a tribal or righteous God, for race and rights have and must defend boundaries, but the Sea “without guards or enclosures.”

Devlin, like Dante, brings to his imagination “the material of actual event which Perse does not encompass.” What for Perse is an undivided divinity and reality, “One same wave throughout the world, one same wave throughout the City,” has been incorporated by Devlin into the particular: thus Devlin’s particulars are super-real within his personal mythology, while at the same time they contain a collective significance that denies their uniqueness. Not even the most personal musing is obscure or unreal.

While ultimately like neither Perse’s sea nor Dante’s rigid structures, Devlin’s vision of “Bilateral symmetries” (quoted below) seem to combine them both into two intersecting cones, one inverted and nested inside the other: gyres, thronged with more or less deific activity in an ever elaborated system, which also reflects his preoccupation with certain ratios.

William Blake, The Goddess Fortune, Watercolor illustration to Inferno, 1824-7. Digital Dante.

William Blake, The souls of those who only repented at the point of death, Watercolor illustration to Purgatorio, 1824-7. Digital Dante.

Devlin’s gyres are not unlike the gyres of Yeats’s A Vision, but they are altogether more productive of poetry. Whereas Yeats’s gyres showed the motion behind an unfolding pattern of historical ages and attitudes past and future and their correspondences, Devlin’s order is apparently open-ended and essentially mysterious. Devlin’s gyres are empty –– until someone engages them. Perhaps this is another meaning to the title, Enigma of the Piano.

The last page of the poem would appear to support such an interpretation:

Yeats’s Gyres.

The Celtic Fringe.

The piano on the piano nobile is locked and out of tune. The caryatids on

the west front gaze into the setting sun, like statues looking seaward.

The March winds are booming across the hills like guns along the horizon.

Woe, woe, for the golden bowl is cracked and broken: who will put it

together again? The Virgin in the chapel sheds an unnoticed tear. The

stone altars that used to be in the chapel have been removed and dumped

at the end of the garden; the idols have had their heads lopped off. The garden

god creeps into the vacuum, as nature abhors a vacuum. There I hear a dull

rustling in the foliage. Look, behind you, for there a shadow falls across the lawn.

The surface of the water of the canal is disturbed, in this flat land. It is

dusk, time for bed and closing of eyes, even for sightless caryatids whose

gaze towards the sea is inscrutable. A piano nocturne is heard in the distance.

Nectarines from Chile adorn a French pewter dish on the table by the mantel.

Even the carp have gone to sleep; the spring flowers close their petals

and hyacinths close down their humid perfume. Where now is God in his fury,

in his anger? The end of the world has been put off so long we at last forget

it, and fall asleep: the sleep of the just. Where now are heaven, hell? All

I hear are the small birds twittering in the leafless quince bushes. Stone horses

are ready to jump down from the chapel facade. All is facade. The nocturne lingers

in the peaceful garden. But who is playing upon the piano on the piano nobile?

I do not know: do not bother me now with such questions. The poet lingers

in the garden of his creation, a city where only ghosts dwell.

I have supplied some more or less corroborating evidence for my various claims (below), but, more importantly, enough to also reproduce a feeling for the book.

Europe is a great labyrinth, surely; is there at last a centre to this

Eurocentric puzzle? This is a myth: a young man goes to Cambridge, becomes

ill, returns against his will to the barren culture of Canada. He gradually heals

and cleaves to Nova Scotia for the rest of his life: renouncing Europe

and her concentric circles, webs of deceit and intrigue. But is there

a heart to the yew maze? Perhaps a yellow tea rose bush at the middle of

it; or a statue garden-god? This search for God or a god in the endless folds

of his cortex: a brain running out of control, must be slowed down

in order to solve the puzzle, or to conclude at last that there was no

puzzle after all: just an over-active imagination, mental fevers brought about

by the too-mild Anglia spring. This young man was used to the remorseless

winters of Canada, unprepared for the delicate, nuanced culture of Europe.

So he became lost in his search for the garden-god. Lost for thirteen long years:

people said, You are beside yourself with too much study. Go for a walk upon

the barren beaches of Minas. Cool down your brain in the wintry blasts.

Do not lose grip of the superiority of Canada. But all this was so

much to ask of this young man. So Europe remained an enticement, a delusion.

He went, at last, by his own admission, beyond Europe and Cambridge. So Europe

could only ever be a partial satisfaction to his ranging, roving, restless

mind. The centre of the maze is reached, at last. Perhaps. He yearns for

closure, which delays and delays in coming. Subliminal messages generated

by the monumental architecture were a constant tease to his restless curiosity.

It was never from the first a plan of Philandros to subvert Holy Church

or to hijack religion and raise it to a higher plane of pure number.

As time went on, Kant replaced Jesus, much to his imagined chagrin,

and numerology the intricate web of systematic theology. Many accused him

of dabbling in dark arts, but he did not see it this way: he continued

every Sunday to go to Mass. If anything, he was given to adoring

Our Lady more than Jesus, and seeing her as being in a covert way

a creature higher than her Son. But he was in a pickle because

at that time he did not wish to jettison religion for pure philosophy or

his new-fangled theory of architecture and æsthetics which few people

would be likely to accept. So he wished to incorporate Holy Church into

his system and thereby elevate it, and show and feel the need to incarnate mere

dry dusty numbers, whatever those numbers in his Christian numerology were.

But the numbers had a funny way of always popping up with renewed vigour over

the great Christian system, and demanding to be asserted in their own right as

subsuming (is that the right word?) all of religion into a new metaphysic which

was at the same time rooted in the description of an anatomical imperative.

But still he went to Mass. It got him out for the fresh air, out of the house,

he explained to himself. But he was still a youngish man in search of love.

This was Parsifal’s quest too. Both were fastidious when it came to love.

Both wanted heart to rule as well as head. Neither could really love unincarnated

numbers. But anatomies informed by the architectural factor would solve the puzzle.

The imaginary Lady flits down the corridors of the palace of the King of

Time. The King is robed in robes of green and gold. He is melancholie againe

because the spring blossoms are faded and fallen. So blind Queen Eva plays

for him a curious sarabande upon the cembalo. The fires in the grates burn with

flames purple and green this cold summer morning. Candles in the dome ignite

fire in the centre of the palace where this folie à cinq gathers for a late

cold supper. The Lady in gray flits back and forth through the enfilade of

doorways in the south front while the clavichord soothes the King who reclines

with his face to the wall. She passes five mirrors on her vain journey, and

sees in each the fading shadow of her wan smiles. Five times she passes and at

last she looks in the last of the series of looking-glasses. Intersection of this

ménage results in implosion of the central dome with no loss of life or

damage to the precious frescoes. The King of Time is a new invention

in this pentagonal palace, draughty on a rainy Monday morning when candles

in the dome must be lit for a game of bridge-plus-one. The King’s Fool

invented this peculiar game for five adults: one woman and four men.

A gyroscope governs the length of each game. The Pope’s birthday

is celebrated with venison pie and stale mead. The altar Easter lilies

in the castle chapel are limp and brown and soon to be tossed out for compost

in the kitchen gardens. The Fatima is adored once again

and the holy candles lit smell like toast. The imaginary Lady in gray

at last ceases her questing and rolls to a complete stop beneath the burnt dome.

Malcolm and Patricia emerged into the courtyard through a very small

door to be faced with the arches of the facade of the Hawksmoor

Library which re-created on its facade a series of explosions in stone.

How peculiar, they both thought, to see explosions followed by implosions

culminating in the grand staircase dome at the north end to show a Universe

which would never collapse in an awful way. Bilateral symmetries showed

how one universe came into being, then fell in upon itself because of a

design flaw which the architects tried to work out by trial and error.

Such commotions, they murmured to one another, and cataclysms worked out

silently in stone. So too, sinister was the collapsing left half to emerge on

the other side as dextrous fingers within a glove of mauve chamois leather.

The building was a representation of The Flood which deluged the old

world. But others revolve forever, without ever finding the answer

and detecting the design flaw. This took æons. Yet the library was

all put up by the masons employed by King and College in seventy years.

After thinking these few thoughts, Malcolm and Patricia ascended the

old staircase and moved down through the central hall of the library.

Encountered down the central axis were a few phenomena of ball lightning,

and they dodged these as best they could. As they approached the bust

of the dead Queen they heard announced in the thick air the word: Checkmate.

Upon hearing this word, they moved their positions upon the black

and white marble floor to allow the King of Time and the imaginary Lady to collide.

The dictionary of homoeros was discovered by Parsifal in the Vatican

Library when he was on a quest in Italy. After this he was assailed

by the cunning one at night by porno culture dreams. All this

was a mystery to the chaste knight. Philandros wrote to him in a

letter: When the Moon turns from white to red, rest assured,

the Dark Man is near. Parsifal wrote back in a long epistle: The

Valley of the Shadow of Death lies between the kitchen and the living-

room. In the palace where he was staying the wind gusted down

corridors to plastered rooms, empty, and falling from the cornice.

Then it rained for a fortnight. In that room the fruit were like a

bowl full of planets. Although he now stood disarrayed, like Japanese

lanterns in a vase. The Sun lies parched and faint and in his grave.

So it was winter when Parsifal was in the Vatican Library, mightily perplexed by

all the strange manuscripts he found there. Treatises on alchemy,

Arabic dissertations, dusty books in an alien script: all collected

and placed there by the Mannerist cardinal, father of the King of Time,

and other great leaders on Europe. The withered leaves and tumbled heads

of freezing roses that seemed to grow in such a cold November,

in Rome, hard by the friary where he was living in a cold cell

until his searches were complete. Philandros wrote in another letter:

O, ripe fruit dropped is heavy, dropped from the ends of loaded boughs

is ready. This was a code. At this Parsifal packed up and left for Heliopolis.

To close, I have provided a quotation that shows Devlin’s “bilateral symmetries,” working at their highest pitch.

The ante-room was decorated with green panels of trophies while the marble

tribune was of chaster pietra serena stone. The queen of Jupiter and her

delegation were in the ante-room, prior to the signing of a grave,

solemn agreement. The tribune was of vitruvian proportions, discovered by a

student of Palladio: a corinthian volume generating moods and

factors of monumentality. Because the scene was so solemn, the queen of

Jupiter had decided to adorn her full, fully displayed bosom with male

rubies from Europa. The malachite clock on the severe table struck midnight, and

the nude Nubian honour guard inspected foreskins, as was the custom in

those places at that time. The Ephesian foreign legion wore silver-gilt

thoracic armour. Several of these men were young, and swooned

when they saw the queen’s exposed bosom. On her full skirts were embroidered

the fantastic images of ears and eyes. Mars and Jupiter were now at peace.

Aztec House was fully lit for this sombre event at midnight with hundreds

of spermaceti candles. Phials of chartreuse were passed around,

and the queen and her soldiers and those of the other delegation drank

it down. The queen then swept out through the ante-room outside into

an awaiting gondola drawn by four dolphins to take her to Ganymede where

a gayer festivity was waiting. Here the high commission from Mercury had put

on a ball. The nude Nubians and Ephesians had gone on ahead to make ready.

Architectural theory was fully in practice here. The ionic volume

on Venus informed the new archbishop of the arrival of the queen of Jupiter.

Read Part III here.