Six Theories About Sofia Coppola

The Virgin Suicides, directed by Sofia Coppola, 1999.

Lost in Translation, directed by Sofia Coppola, 2003.

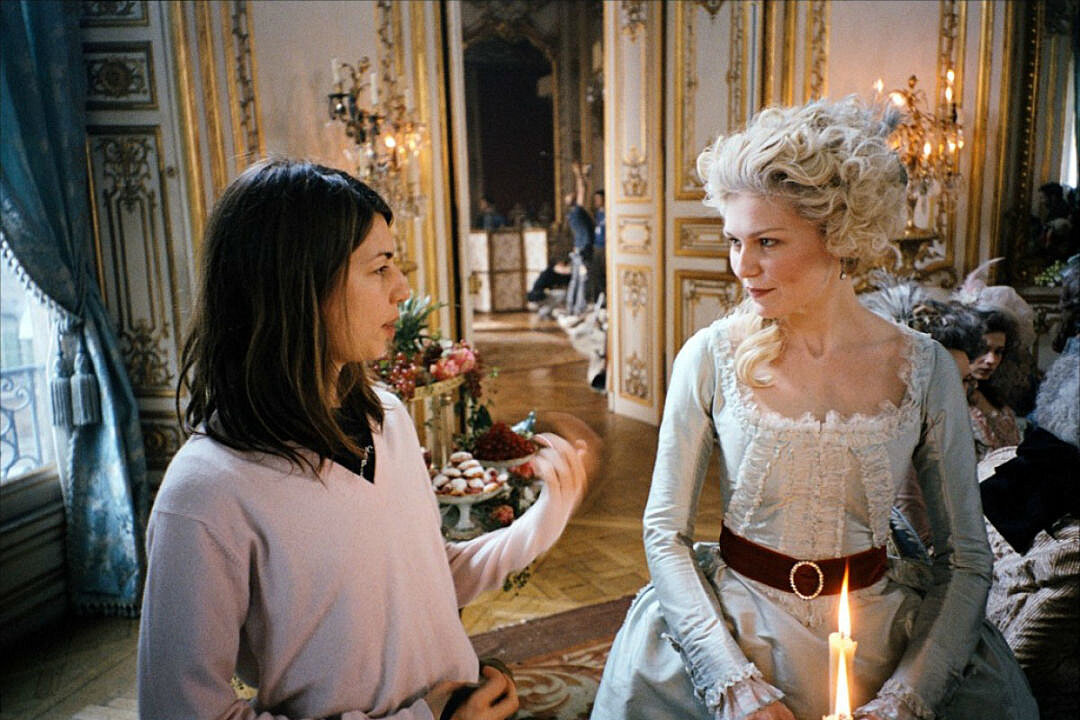

Marie Antoinette, directed by Sofia Coppola, 2006.

Somewhere, directed by Sofia Coppola, 2010.

The Bling Ring, directed by Sofia Coppola, 2013.

The Beguiled, directed by Sofia Coppola, 2017.

On the Rocks, directed by Sofia Coppola, 2020.

Six Theories about Sofia Coppola

Is Sofia Coppola the most overly critiqued and theorized director of her time? Since her full length feature debut Virgin Suicides in 1999, she has been the subject of think pieces, scholarly panels, YouTube breakdowns, and monographs. She's the auteur of girlhood, she's the pretty princess of Hollywood, she's the female gaze, she's our female Truffaut. But was it because her movies are good, and worthy of all of that thinking and consideration, because she is Hollywood royalty and basking in the glow of her father’s career, or is it just because she debuted at a time when there were no other high profile indie American women directors focusing their attention on the lives of girls and women?

I add all of those qualifiers simply because, in our rush for mainstream acceptance, we tend to forget the women who have been toiling away in the shadow of the male dominated industry for decades. Catherine Breillat was giving us stark depictions of girlhood for years before Coppola's debut, Chantal Akerman and Lucrecia Martel had already used domestic spaces as suffocating spaces of confinement in iconic works. But those works were too thorny, too hard, too weird. We wanted something soft and pink and heavily scented, something disposable. Something that could win an Oscar. And here came Coppola, giving us mainstream accessibility wrapped in an “artistic” gauze. Now when we talk about important women directors in our film culture, we talk about Patty Jenkins, rather than our actual geniuses.

The same impulse that made us think Greta Gerwig was an artist instead of a step-mom from the suburbs let us think Sofia Coppola was a hero to, like, see us. We're fucking starving. So it makes sense that a lot of people would breathlessly support whatever she did, then start to hold her to impossible standards, then spill a lot of ink trying to figure out why she failed to meet those standards.

As many critiques of Coppola's films as I've read, I never felt like they fully explained why her films were so pleasing but also what I found so lacking. Other than Bling Ring, which I believe to be a perfect film, I find the conversation around Coppola's work to be more interesting than the work itself. And with the release of her new film On the Rocks, which seems to have been made in direct response to some of her most vocal critics, it seemed like a good moment for a reconsideration. And yes, to contribute to the already too much critical response to Coppola's work.

The Bling Ring

Sofia Coppola is the Female Gaze

There is a John Berger quotation that shows up on Tumblr a lot.

A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping. From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually. And so she comes to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity as a woman. She has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life. Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another....

One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object — and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.

I've always distrusted people who relate to this passage. Obviously “woman” is doing a lot of work here, creating a sense of universality when really it only applies to a very small subgroup. It's women who meet the very narrow standards to be considered worth looking at who are objectified and who internalize this process. A lot of people who identify as women, including myself, read this passage and start rolling their eyes. The gaze bounces off us, if you will.

I've already written before about how much I hate the term “the male gaze,” and I have a horror of repeating myself, but let's just summarize by saying the idea that one's gender has a measurable effect on how one looks at the world, or even the idea that looking at something inevitably turns that thing or person into an object, is boring and reductive and it is used as shorthand by people who would rather rely on tropes than actually think about something. But the idea that there was something revolutionary about a woman director and the way she looks at the world, that there is something different and important for Women about Coppola's films, is a recurring idea in the critical responses to her work. (Just search for Sofia Coppola + the Female Gaze and you'll see what I mean.)

Marie Antoinette

Sofia Coppola doesn't seem to work so much with “the female gaze,” whatever that might mean. She doesn't watch women so much as she watches men watching women. The Virgin Suicides is filtered through its male characters, we are watching these girls be watched by these boys, and there's no wink at or break with that gaze to suggest anything exists outside of it. Outside of male attention, Charlotte of Lost in Translation is almost entirely silent and empty. She watches a religious ritual by herself and has no idea how to process it. She reports to a friend that she didn't feel anything.

There is a certain type of woman that a man likes to “gaze” at, and it just so happens to be the same type of woman Coppola uses in her films. Gazing is different from leering or just watching, it's more sophisticated and transformative. It is the look of the artist. Coppola makes sharp distinctions between women worth looking at (the sexualized and the cheaply beautiful) and those worthy of the gaze. They are the women of French films and of impressionist paintings. They are soft and sad and mysterious. Her characters, particularly in her early films, seem like girls recreated after their extinction through descriptions of what they were like in pop songs written by men.

When the girls die in Virgin Suicides, they all die beautifully. There's no pool of vomit, no congealed blood, no blackened and protruding tongue. When boys dream of dead girls, they dream of Sleeping Beauty, not of a blotchy, bloated corpse.

The Virgin Suicides

Sofia Coppola is a Taurus

The Taurus Sun tends to define and express oneself through the material realm, selecting a brocade for that couch not because it is pretty, although they do love pretty, but because it is an external representation of some truth about themselves. Taste becomes confused with character, the material realm becomes confused with the spiritual world.

Coppola, like fellow Taurus Wes Anderson, reveals her characters' inner workings as much through the things they have around them as by what they say or how they behave. Her tableau of girlhood in The Virgin Suicides is one of fragile prettiness, defined by the mysterious and spiritual (tarot cards and Catholic saints), the ephemeral (perfume bottles), and the horror of embodiment (a Costco-sized haul of tampons in the bathroom). The characters are thus shown to be both enhanced by their girliness and oppressed by it. Marie Antoinette is a cacophonous splendor, but the delicacy of our princess is revealed in what and how she consumes — prettily, daintily — versus the loud and covetous appetite of lower class Madame du Barry.

The richness of the very sympathetic Marie Antoinette is in stark contrast to the acquisitiveness of The Bling Ring. Each has shopping montages and conspicuous consumption, but the finery of Versailles is replaced with the garish, sequined stuff of a starlet's closet. It's very much of its time, the weird and artificial first decade of this century, when, with knock-offs and mimicry, you couldn't tell if something was worth $1000 or $10, if it was silk or polyester, until you checked the label. Which is of course why fashion started to be nothing but labels and logos, patterned on every square inch, because how else would the moneyed differentiate themselves from the Forever 21 shoppers of Middle America? The girls of the Bling Ring go after rhinestones as well as diamonds.

If there's anything wrong with Laura of On the Rocks, it is that she does not enjoy her wealth enough. She is a writer, and we know she is a writer not because we see her reading or thinking or discussing literature, it's because she wears a Paris Review t-shirt, has a collection of tasteful leatherbound notebooks, and has a bookshelf with perfectly curated candy colored books that look like their spines have never been cracked. We do get a small glimpse at her manuscript, and she seems to be writing a Nordic murder mystery.

She is just a regular mom, wearing a stained shirt and the same jacket over and over. She's just like us, the film insists, it's just that she makes her instant macaroni and cheese in a Le Creuset and not a pan she bought at the Aldi. Her father, a wealthy art dealer who keeps talking about a Hockney he wants to unload, enjoys his wealth immensely. He goes to parties, he eats caviar as a light snack, he drinks daytime whiskeys, he's got a Queen Mary to catch. He knows the joy of wealth is to make yourself frivolous, but his trust fund daughter scolds him for being a bad family member. She retreats to her boring family with their cashmere throws and ever available domestic servants and this is reasonable and good because it is tasteful. Her wealth, which is subdued and expressed as comfort rather than extravagance, is the more moral wealth. It would be easier to see the family as the better alternative to excess and waste if they weren't often the exact same thing. It's interesting how many films end with the characters fleeing their comfortable, rich lives, only to find the next character in the next film wrapped in velvet and diamonds yet again.

When I searched for “Sofia Coppola” to fact check this piece, a suggested headline was “Sofia Coppola on Chanel Handbags: 'Your First One is a Rite of Passage'.” While I was in the middle of this Coppola marathon, I dreamed of auction houses and display rooms, of decorative objects and upholstered furnishings. The only thing in the rooms that didn't sell was a small tortoiseshell Buddha.

On the Rocks

On the Rocks

Sofia Coppola is Racist

This is perhaps the most worked angle on Sofia Coppola Film Studies at the moment. Her films have always been white-centric, even when not exclusively populated by white people, but this was rarely called into question until quite recently. Her decision to remove the slave character — and all sense of the racial motivations for the Civil War in her Civil War film The Beguiled — sparked a re-evaluation. People went back through her films and noticed how frequently she has used people of color as props; there are several Hispanic men in Somewhere, for example, but they are all there as kindly service workers tending to our rich white protagonists.

Lost in Translation got a free pass upon its initial release for its depiction of the Japanese... characters is too generous a word given how Coppola uses them in her story. Scenery? They are there mostly as punchlines, and the jokes aren't even that good. There are a full six scenes where the confusion of 'l' and 'r' sounds when a Japanese native speaks English is played for laughs, except it was not even that funny the first time. But with the controversy over The Beguiled, Lost in Translation has also been retroactively declared problematic. The think pieces and negative reviews and accusations of racism were so intense Coppola gave an interview claiming her 10-year-old daughter was distressed by all of the negative attention.

The casting decisions behind her most recent film On the Rocks seem to be in direct response to this racism charge. She tells the story of a rich black family whose security is threatened by the possibility of the husband's infidelity. The main character Laura, played by Rashida Jones, must come to terms with her white father, played by Bill Murray, a longtime philanderer and ladies’ man. When I say “security” I obviously mean emotional security. A visit to Laura's mother's estate shows she has the inherited wealth that will allow her to recreate her enormous Soho apartment should she be kicked out of her husband's. Coppola is careful to accessorize this couple's blackness. She shows Laura watching a Chris Rock stand up special, and she at one point dresses her in an A Tribe Called Quest t-shirt.

Still, she can't help herself. When Laura and her father of On the Rocks head to Mexico, the film cues us to the change in locale with a blast of stereotypical Mariachi music and we get a shot of Laura waiting at the airport in front of a display of bright, sequined sombreros. Is this more or less racist than the many filmmakers from Steven Soderbergh to Denis Villeneuve who choose to tint all of their film scenes set in Mexico with a sickly yellow hue, making it look like the country itself is poisoned and giving its people an unnatural sheen? Is an imaginary Mexico made entirely out of resorts for wealthy Americans more or less racist than a Mexico populated entirely with narco cartels? It's truly hard to say.

Coppola gives a reason for removing the black character in her remake of The Beguiled: she claims she was interested in retelling the story of Thomas Cullinan's novel and the 1971 film adaptation with Clint Eastwood for what it had to say about the power struggle between men and women, and was less interested in the historical setting. If that were truly the case, it's a strange story to want to tell. Just do a Medea or something, Sofia! And it does of course speak to her disinterest in complication or in context that she would even think of the Civil War and not have to think of slavery as an essential part of the story.

But it's interesting that the things that are so wrong with Lost in Translation are equally wrong in the section of Somewhere set in Italy. There, too, Italians are just there as part of the set design or as jokes. Her fish-out-of-water scenes about travel and encounters with people who are different from her protagonists tell the same stories. The baffling Japanese escort who wants Bill Murray to “lip” her stockings is reformulated into a massage therapist who strips down naked to rub down Stephen Dorff. Each of her characters is so used to living in enclosed homogeneous spaces that anyone who exists outside of that realm looks like an alien, a fool, or a threat. And rather than using these interactions to show the ridiculous limitations of her characters — their prejudices and paradoxical provincialism — Coppola is comfortable making the foreigner and the outsider look absurd. Or, in the case of Colin Farrell's wounded Union soldier who infiltrates the cozy Confederate sisterhood in The Beguiled, an existential threat that must be eliminated.

The Beguiled

Sofia Coppola is Melania Trump

Reviews often talk about how enclosed Coppola's films are, using the words “hermetic” or “cloistered” to describe the suffocating environments she traps her characters in. But the words aren't quite right, evoking as they do deprivation and spirituality. Coppola's enclosures, including enormous Manhattan apartments, hotels, plantations, palaces, and girlhood itself, suffer no deprivations and are enhanced with not even a whiff of the holy spirit.

Instead of a hermitage, what the settings of Coppola's films actually remind me of are the Instagram feed of Melania Trump, before she deleted all of her past photos. Kate Imbach did a brilliant analysis of her pictures, and just how many of them were taken through car windows and hotel windows, from the back seat of a car while being driven or from great heights at the top of buildings looking down. Everything is rendered slightly blurry, slightly smudged, and held at a remove. The pictures have a romantic cast to them, but the subject is rarely her family or the buildings on the other side of the glass, but simply the glass enclosure she has built for herself.

Since the election of Trump, there has been an effort to speak for Melania. To project onto her shiny flatness an image or create some depth. Maybe she's showing her political displeasure through her choice of outfits? Maybe she's signaling to the world her disagreement with her husband through this hand gesture? Surely by doing this one thing she is trying to say she hates her husband and his presidency and all the rest of it. But we always got it wrong. The pictures, however, showing both what Melania sees as important and worth looking at and documenting, suggest a different possibility. As Imbach puts it, “She is Rapunzel with no prince and no hair, locked in a tower of her own volition, and delighted with the predictability and repetition of her own captivity.“

There's something similar going on with Coppola. Feminist critics and scholars have done a lot of work to suggest Coppola is trying to show the way we limit women's lives and how tragic this is. But she, too, seems to delight in this separation from the real world. The real life Marie Antoinette, yes, began her rule as a teenager, but she died in her thirties. Coppola prefers the girlish ruler. The actual real incidents of her life, including the death of her mother and the birth and death of a child, are all passed over — in the case of the death of her child, it is made light through a visual joke, Antoinette’s portrait being updated with a new baby and then the baby quickly being covered up. Anything that might age her is removed, and her most absurd moments — like the second property she went to and had everyone cosplay as poor people in a pretend agricultural village while actual human beings starved just kilometers away — are softened to seem charming or playful rather than morally objectionable.

She chooses to keep her characters in their enclosures not to make some feminist statement about the oppression of women. She delights in enclosures. These spaces prevent growth, responsibility, and accountability. We don't see the Marie Antoinette who must face the consequences of the pleasure and excess she enjoyed. Her characters are all taking more than their fair share of the limited resources of food and money and pleasure, but we very rarely see the people from whom these resources are taken. And “the people,” of course, remain unseen until they emerge as a dirty, loud, vulgar group of protesters in Antoinette. The slavery that allows for the girls' school in the Confederacy to exist in The Beguiled is rendered entirely invisible.

All of these towers she puts her characters in are made to be temporary. The ever spiralling upward pleasures and decadence of Versailles is as if made of spun sugar; it can’t possibly endure. The hotels of Somewhere and Lost in Translation are meant to be liminal, not places of permanent residence. Even the girlhood of her protagonists is yet merely one state of development, you are supposed to grow up eventually. But everyone and everything remains stunted, and the longer Coppola works the more grotesque that lack of development becomes. She leaves her female characters in The Beguiled in a permanent Confederacy, responding with violence (although violence from which the camera politely turns away) to anything that asks them to rejoin the world and face the consequences for the way they have lived their lives.

Coppola has no imagination for what might exist outside of these structures. It's all just a blank space. When someone leaves their chosen enclosure of the hotel in Somewhere or Lost in Translation, we get another heavy-handed song choice — “listen to the girl as she takes on half the world” — and then credits. Again, it's a choice to remain in potential rather than in clumsy actuality or mess. No one ages, no one grows, no one escapes, no one faces consequences. Interviewers keep asking Coppola if she'll do a sequel to Lost in Translation, because people want to know what became of those characters. Guys! She doesn't know.

Sofia Coppola is a Product of Nepotism

Hollywood is mostly legacy families at this point. Every new starlet and “promising filmmaker” turns out to be the daughter of someone either rich or famous. An industry that was built by refugees and immigrants has now become a stagnant gene pool, as we are made to believe that it's the wealthy disappointing sons and ambitious daughters of generational access who are best poised to tell stories about what the world is like now.

So it's not that interesting to talk about how Sofia is the product of Hollywood's Golden Age, that her famous father Francis Ford Coppola produced her films and she inherited her father's production company and that her frequent collaborators are other family members and friends. It's true of just about everyone making film and television today. It would be interesting if Coppola were willing to dig into the complications of legacy and inheritance. Most of her characters come from lineage, experience their worlds through these relationships of access and nepotism, and yet they are not questioned. The women who try to gain access to these worlds of wealth through scheming and social climbing, like the Bling Ring girls, are of course delusional messes.

Charlotte in Lost in Translation gains entry into a world not through her father but through a famous photographer husband. And despite the fact that she shows real disgust with the man she married, her lip curling when she hears his fake laugh around a celebrity, and that she seems to hate his famous friends, she can't not be around them.

The reason why Charlotte is so relatable to so many — and me too as a 24-year-old, I was also an idiot — is because she is certain of her specialness and yet terrified to actually make an attempt to do something, get a job or take up an artistic pursuit, because this might reveal her mediocrity. In a long series of examples of Coppola using song lyrics to narrate her films in the most literal way, she uses The Pretenders' “Brass in Pocket” as Charlotte's karaoke choice, with her singing directly “I'm special, so special / I got have some of your attention” in a coquettish way to the Bill Murray character, Bob.

So she stays purely relational, hanging out with the famous and the creative through her husband and befriending not a peer who also feels lost but an older celebrity. She gains entry into his world not by being smart or funny or interesting or thoughtful or kind but simply by being pretty. But not in the same way as the other women who use their prettiness, like the movie star Kelly, whose bubbly airheadedness is portrayed as pathetic. Charlotte's beauty is more sophisticated and less obvious, and she knows who Evelyn Waugh is.

The troubling father figure of On the Rocks lectures our sweet and talented (we are told rather than shown) Laura that what a woman needs is not a husband but a daddy. He lectures her on the unreliability of husbands, who will always cheat, always lie, always want more attention and affection than a wife can give. But a daddy, he can solve a woman's problems for her, make her decisions, show her the world.

But when Laura comes to question the inheritance she has been gifted from this daddy, she only questions the emotional trauma of abandonment and infidelity, not any of the money, art world, New York social scene stuff. Nor does she question whether one is tied into another, whether the emotional corruption is integrated into financial corruption. She can heal from one through a series of conversations while retaining the other.

Sofia Coppola on the set of Marie Antoinette.

Sofia Coppola is Cringe

I'll admit to impure motivations when it comes to my fascination with Sofia Coppola. There's an involuntary association at work here, and a cringe factor. Because women are still seen as a subcategory of human beings, a figure like Sofia Coppola is positioned to be not just a woman filmmaker but a filmmaker for women. She is the female gaze, she is telling stories of women, she is a chronicler of “girlhood” — whose girlhood? I want to break the association and refuse the representation. This is not my girlhood, this is not my female gaze. It's why I am more interested in writing 4500 words and spending 20 hours of my life watching her films in order to dissect them rather than Zack Snyder. (The YouTubers seem to have the Snyder situation under control, my efforts are not needed.)

This painful association runs through a lot of popular culture analysis, as we work to define which intellectual properties do the best job of defining who I am as a human being (or my gender, my race, my sexuality, etc). The ones who embarrass us get our ire. I see plenty of Sofia Coppola defenders working hard to maintain these associations because her soft glow is flattering to their sense of selves. It's fine! I just want to make sure you know, I am decidedly not like these characters. I'm different, I'm special and so on.

There is something similar going on within the work of Coppola. She presents bad women, women she too does not want to be associated with. She knows the stereotypes that come with the aristocratic and the out of touch, and she gives them form as a woman to be mocked or scorned in most of her films. She knows the parents of children in private schools are seen as narcissistic and boring, so she creates a narcissistic and boring character played by Jenny Slate to distinguish her own more sensitive mother to be compared against.

Sofia Coppola alters the historical record for Marie Antoinette to make Madame du Barry — a former sex worker who climbed her way into the royal court — look like a fool. She renders her tacky, loud, and tasteless, yet still eager for the approval of our little princess. It's mentioned repeatedly that du Barry bought her title, rather than earning it through birth. Those who want to climb above their station — girls who want to fuck famous actors, sex workers, and the striving poor — are drawn more harshly than necessary. Women who are overtly sexual are made again and again to look embarrassing or shameless. Marie Antoinette recoils from du Barry for her loud laugh and bad garments, Cleo scowls at the women flaunting their cleavage and flipping their hair to gain the attention of her famous father in Somewhere. The unnaturally flamed-hair lounge singer in Lost in Translation is turned into an easy blackout drunk gag, the immediate implication being that she's fuckable only under the influence. Even the sound of her voice rankles our protagonist.

But in critical cringe mode, it's easy to overlook the good in someone's work, working so hard as you are to make the other person look bad so you'll look good. The pleasures of her films, the jewelbox nature of her sets, the rescuing of Kirsten Dunst from airhead roles and superhero nonsense, her skillful use of the craft of filmmaking, the tight control she has over her work. She tells a good story. But it is just one story, told over and over and over again. One wants to rescue her from her tower, but it doesn't seem, yet, that she's done playing Rapunzel.

Somewhere