“Root-Bound” by JPW3 at Night Gallery

I have only recently become aware of JPW3 (J. Patrick Walsh), and this is my first time seeing his work in person. I was surprised at the contrast with the photographs of his 2017 solo show at Night, Drifting the Bog, which featured paintings and an installation that appeared rather forgettable. For Root-Bound, Night’s blurb states: “[Walsh’s] works acknowledge our apocalyptic landscape while finding nature’s persistent ingenuity and adaptability.” The show is split between three sculptures in Night’s outdoor garden, and six paintings indoors.

Through a conceptual gesture, the sculptures agree with the ideological register of the show set by Night. Three hollow and rusted wedges point to the sky while they dig into the earth. One can imagine that even if they were monumental, they would be boring to look at: their proportions are dull, as is the material, the shape, the orientation of the three of them in space, and so on. The piles of dirt flung and piled on their bases gesture towards something about the absorption of all artificial products back into the natural soil, the eventual rotting away of manmade metal objects back to their source. But the aesthetic effect is underwhelming, like gift-shop Land Art.

The difference in some of the paintings in Root-Bound is that of an artist who’s up for the task of reckoning with why he’s making art at all. They seem to embody a dedication to aesthetic prowess rather than cheap symbolic or conceptual gesturing. They confront the difficulty of exploring beauty, which today is too often neglected. Present is an expansive, almost ecstatic approach to rendering beauty, reminiscent of the spirit of certain O'Keeffes. Not all of these paintings are very good, but the ones that are are captivating. There is a richness in color and fullness of form in these works that drew me into them immediately, and held me there. Within them, colors and shapes seem to crumble and grind together, the complexions plow through each other and themselves.

frog cup, 2021

The quality of the oil sticks used lends every heavily saturated surface an alluring texture — all the pictures are salted with their own luminance. They are bold, enveloping, and seductive, especially First Bloom. These paintings are as aromatic as Rimbaud; they are libidinal, heavy, forceful, delicate, sensitive, intoxicating. The not-so-good ones — Push, 13 green Beans, and emo flower — are not-so-good because in each of them Walsh failed to yield to the picture, leaving it behind merely as the debris of his impulses, or otherwise caved to external mandates. In other words, in the good paintings there is a naive wonder in the artist’s expression, while in the others there is a pervasive sense that the artist capitulated to the pressure to satisfy trends.

First Bloom seems to both emerge from and collapse into the four anthers at center. Like other paintings in this group, it is speckled with stars. These small circles anchor the movement of immense shapes, which dance around the central bloom hypnotically. Everything is vertical; propped up and flattened with blushing colors. There is a burning procession of jewels — garnet, hyacinth, jonquil, sapphire — billowing around this central bloom. A fault line runs from the center of the picture to the bottom, which to my eyes could be nothing other than a linea nigra. Creation is a theme Walsh has engaged throughout his work, but it is especially vibrant here, articulated by flowers and space and rendered with intense energy.

First Bloom, 2021

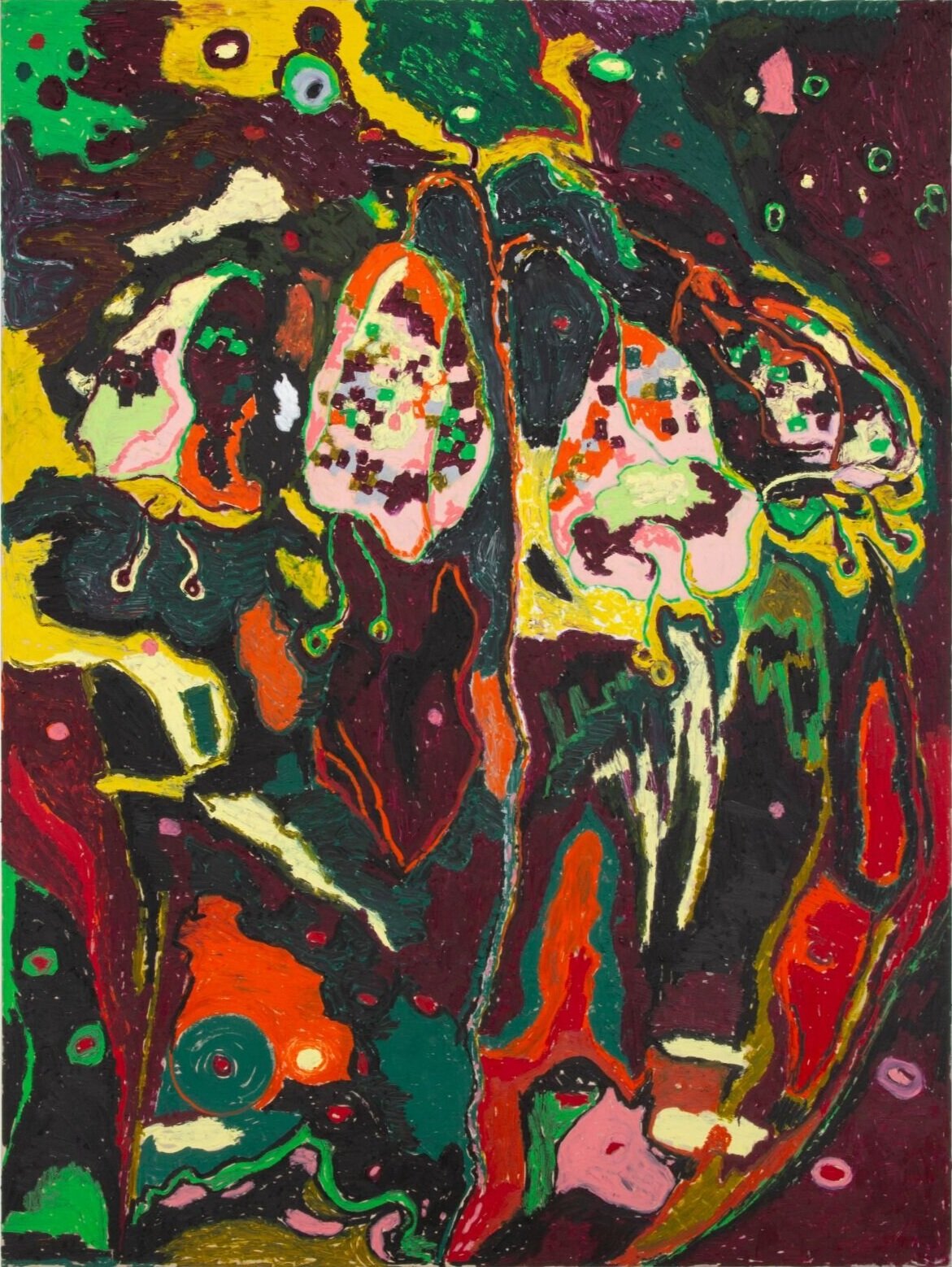

Root-Bound is another memorable painting in this show. Whereas First Bloom is an image like a galaxy accreted around a pistol, with no end or beginning, no ground or sky or horizon, Root-Bound begins on firm earth, drifting, rising, and dissolving into a celestial dream. The landscape is animated as a fairytale. Everything is organized in a layer cake–like vertical stack, supported by a grid, which glimpses out past the nebulous upper half of the painting. Again a linea nigra folds this picture into two. Its double function as a stem renders the ovule into a cosmic navel. The image of the flower collapses into the image of Earth and space. Here is the glimpse of the intoxicating wonder which marks the good works in this show. Unfortunately, Root-Bound sacrifices too much to an attempt at charm: it tries too hard to fit everything into the picture, and so its compositional organization feels at once forced and quaint. As being the namesake of the show implies, this painting wants to be the center of gravity for the rest of the paintings. Ultimately it cannot carry that weight, nor should it.

Night informs us that “root-bound” is a condition in which a plant growing in a small container coils its roots in order to maximize their surface area. It is the vaguely misanthropic metaphor of the show that nature manages to find coping mechanisms for our ever-increasing domination over it, with the long-term vision of all that is artificial returning to natural systems at some point in the solar timeline, a veiled desire for self-annihilation. The double-metaphor of the show is the notion not of a return to a past, but of an inescapable bindedness to our roots, to nature, a longing captured vividly throughout, especially in the painting Root-Bound. It wants to place emphasis on continuity rather than change — it longs for the continuous experience of the ancients, a world that just goes around. And yet the quality of the pictures asks the viewer to change their mind about how a floral still-life might be painted and experienced. And, in contrast to Walsh’s past work, the pictures seem to have demanded a change from him as well. The works are advertisements for creation as much as for nature. But what is good about the show is not the way the artist is tying into certain lines of discourse about 20th century art, or certain attitudes towards the organic and artificial, but the richness of the images.

Root-Bound, 2021