The End of Avant-Garde Film

INTRODUCTION

First published with the essay it introduces on November 4, 2021, but revised by the author December 12, 2021.

When editor Gabriel Almeida asked me if my 1986 essay, The End of Avant-Garde Film, published in 1987 in Millennium Film Journal, could be reprinted in Caesura, I was pleased. This essay attracted some attention, and protestations, in its time but is not much read today. I then began thinking that, in light of all that has transpired since, it might now seem curiously outdated.

It was written at a kind of inflection point for "avant-garde," or "experimental" cinema. Two decades earlier, major filmmakers started to teach filmmaking in colleges, and the films I most loved, many made out of deep personal necessity, as a way of deciding whether, and on what terms, the filmmaker could go on living, were now overwhelmed, numerically at least, by class assignments, some made out of commitment and passion, but most not. Younger instructors, too, often seemed to lack urgency in their own work and in their advocacy for cinema. Noting this change was a motivation behind the essay. Meanwhile, two decades after the essay, the shift to video, the incorporation of moving image work in installations, the presentations of both videos and films in gallery settings in which seeing a work from beginning to end was itself devalued, had changed the terms in which many think about cinema. When the Museum of Modern Art, New York, projected a video of Hollis Frampton's wonderful short film Lemon on a gallery wall on which fell so much ambient light that one could not see the rectangular borders of the frame, a presentation that I feel sure would have horrified Frampton as an admirer of the photographers Paul Strand and Edward Weston, the integrity of the film composition was totally obliterated. I want to believe that the MoMA would never display a painting in a way that prevented the viewer from seeing its borders, and I wondered if the fact that this iconic museum would think it could project a film in such a manner meant that an idea I care so much about, that a film has its own formal integrity worthy of that of the other arts, is in danger of becoming irretrievably lost.

My essay's central claim is that, since 1966, few great new "avant-garde" filmmakers have emerged. The thinking behind this idea was already being critiqued at the time of the essay's writing. Replying to a one-page statement that helped give rise to the essay about a year earlier, one filmmaker objected to the whole idea of the "masterpiece," saying that it reflected "authoritarian value systems" and served the interest of critics and curators. Since I had been unemployed for some years at the time of the essay, I wondered how I could now put advocacy for the masterpiece to my own benefit, but I never did figure that out.

My underlying view of art, and the type of film that remains my principal, though not only, model for greatness in cinema, has been bypassed by much that has happened since, in particular the emphasis on the politics of an art work, and on various aspects of the artist's identity rather than complexity of internal form. The ideal of an art work as a finely tuned and brilliantly constructed mechanism of parts interacting with each other to make an almost-miraculous whole, which can affect a viewer with no external knowledge of the work or its maker, has receded. I am nonetheless reluctant to believe that this notion of art, which has a history going back at least a thousand years, should be abandoned. If all manner of "diversity" is a worthy goal today, should we not include art based on the expressive and transformative powers of internal form? This is what I have always taken from the films of Markopoulos, Brakhage, Kubelka, Baillie, Breer, Frampton, Gehr, and many others. Seen in that context, the essay that follows can be taken as a plea for pursuing moving image making with far more care and precision than is usual today, and for the artist accepting responsibility for attempting to make a truly original work that can fully engage any viewer's senses and mind with emotion, thought, and vision.

One important qualification, though, is that I can also appreciate work that does not appear to hold up under my "internal complexity" and "worthy-of-classical-music" standards. In recent years there has been much art, including in independent or avant-garde cinema, that takes a certain modesty of purpose as part of its goal, and some of it is wonderful in the ways in which it speaks to this idea while rejecting the earlier grand aspirations toward what P. Adams Sitney once called "the myth of the absolute film." His phrase and insight have long had personal resonance for me, characterizing many of my own favorites, from Brakhage's The Art of Vision to Baillie's Quick Billy, to not only Hollis Frampton's Zorns Lemma, but his two subsequent series, to several long films by Michael Snow, to Peter Kubelka's shorter Unsere Afrikareise, to certain even shorter films by Robert Breer, and of course to Gregory J. Markopoulos's Eniaios. Yet one can also critique the arguably arrogant push toward a determinative dominance in such works. Then, too, the ways in which "outsider" art avoids older traditions has a few parallels in cinema. I have long been an admirer of the seven films of the Navajos Film Themselves series described in the book Through Navajo Eyes, films made by Native Americans who at the time of their making, 1966, had had almost no exposure to cinema or other "media." Their fresh and ingenuous approach to what, for the makers, was a new medium is part of what makes the films so rewarding to view.

Also, while I have seen the work of a number of new filmmakers in the decades following this article's writing in 1986, many disappointments along with shifts in the direction of my own efforts have meant that I am hardly current in the field. Therefore, this article is thus in no way an assessment of the present scene, though I hope the general perspective it offers is still of interest.

//

I

Imagine a world…

— Stan Brakhage

In 1963, when I was fifteen years old and growing up in New York City, a friend of mine read a Jonas Mekas column praising a new “underground” film, went to see it, and was very impressed. He told me about it, and I went to the next screening of it with him. There was a certain adventure to all this for an adolescent: going to what seemed then like an out-of-the-way part of the city, sitting in an audience of older, somewhat strange-seeming people; seeing a film of a type I'd never even heard of before. But the real adventure began when the film was screened. I had never before imagined that the colors and shapes of the seen world, whose sensuality and texture had fascinated me since childhood, could be arranged into such a perfect expression. Every color, every object, every image seemed to gain energy from all that surrounded it. The time-crossing editing form was unlike anything I had yet encountered. A whole new possibility for seeing and thinking — and most importantly for understanding that seeing and thinking could be intimately related, interdependent acts — was opened. I came to see, feel, and understand my own capacities for perception, thought, and imagination, far more deeply than I had before. My life was forever changed.

In the months that followed, I sought out whatever underground films I could find. New York, in an ignorant and absurd attempt to “clean things up” for the 1964 World's Fair, had endeavored to shut down all variety of activities that seemed even potentially questionable, and that included "underground" film. Thus I would often go out to Queens and see films projected on a bedsheet in someone's living room for a small fee. While some of the works I discovered did not appeal to me at all, many others affected me as deeply, albeit in a variety of different ways, as had that first film, which was Gregory J. Markopoulos's Twice a Man. What had been a single newly opened possibility quickly became a multitude.

From the beginnings of my interest in cinema, then, I have expected a number of things from the medium at its best. A great film for me is first of all a coherent cinematic expression in which each image has a reason for being where it is and a reason for following the previous image: its filmic form is connected to some kind of meaning, however untranslatable that meaning may seem. The work as a whole affects me strongly, ecstatically: it seems ambitious and complete enough to offer, in its totality, not merely the self-expression of a personality but also some sense of a whole lived life, an entire consciousness, a whole form of thinking, a different possibility for being. In my twenty-three years of involvement with the medium since 1963, as a film programmer, writer, teacher, viewer, and filmmaker, I have found no reason to expect anything less than what that initial viewing experience offered. Instead, I have every reason, as both the medium and I mature, to expect even more.

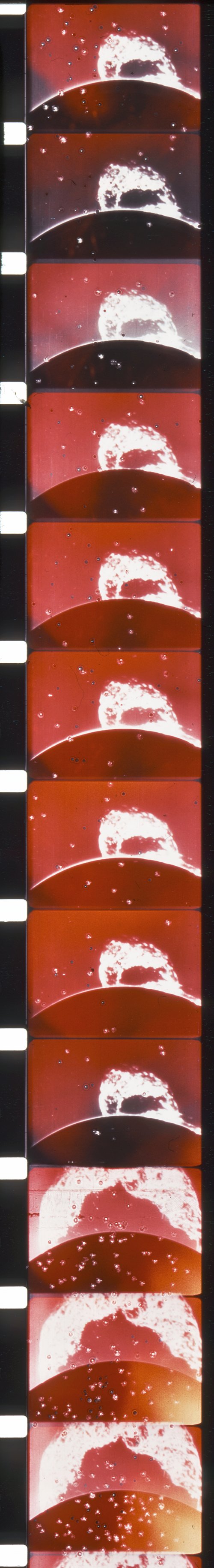

Sequence of frames from Twice a Man, by Gregory J. Markopoulos (1963).

II

Cézanne was…oriented toward the idea or the project of an infinite logos.

— Maurice Merleau-Ponty

The initial masterpieces of American avant-garde film were made in a position of distance — even complete alienation — from the mainstream mass-market tradition of Hollywood filmmaking and from the mass culture of which commercial filmmaking is a major part. This was not merely a question of limited means producing different results, although surely the inaccessibility of sync-sound filmmaking in the initial decades was an important influence on the kinds of films that were made. Indeed, the whole history of the movement might have taken a different, and perhaps less radical course had Hollywood or, less grandly, some arts community similar to that which exists for painting, taken a different attitude toward this movement's first flowerings. Nonetheless, the alienation of avant-garde filmmakers from the mainstream culture that characterized this movement, particularly in its initial decades, was not merely a question of different “aesthetics," or different tastes. Avant-garde films had an ethical difference from mainstream narratives as well. An avant-garde film addresses each viewer as a unique individual, speaks to him in isolation from the crowd, invites him to perceive the film according to his own particular experience and perception, to see it differently from the way the viewer seated next to him would. This is a result of the individuating techniques of a long line of filmmakers from Brakhage to Gehr, in which techniques make the act of perceiving the film a part of the experience of it. Rapid camera movement, rapid editing, an active camera that encounters what it films in a number of surprising ways: these and many other techniques encourage the viewer to think about what he receives, using his own individual faculties, rather than simply passively absorbing a stream of images. In Christopher Maclaine's great work The End, this viewer individuation is effected through the soundtrack as well as the editing. Maclaine's voice at one point exhorts the viewer to make up the story himself. At another he warns each viewer that “the person next to you is a leper,” carrying the separation of viewers from each other to a hilariously exaggerated extreme. The techniques of fragmentation and disjunction of continuous space, time and narrative, and the visual techniques of making each image unique, make the act of seeing an avant-garde film an "adventure in perception." The viewer finds that the film speaks to him not in the ways in which he resembles the crowd, or through the kinds of seeing we all share, but rather by sensitizing him to his own individuality.

The many characteristics of avant-garde filmmaking that separate it from Hollywood practice represented a social challenge as well. To the mass culture conformity of the postwar decades, filmmakers laid down a challenge to all comers to recover their own individuality. To be affected by an avant-garde film was to have a whole new possibility for creative seeing and thinking opened. Behind this lay the filmmakers' desire to strike out against a society which, at its most extreme, conceived of each of its members as cogs in a wheel, and, where what would seem now to be small eccentricities of dress and manner were in fact taken then as major acts of rebellion. It is no accident, for instance, that a large proportion of the founding filmmakers were gay men, in an era when being publicly gay was itself considered an anti-social act of major proportions.

The degree of alienation that these initial filmmakers felt can be seen in the degree to which the themes of death, suicide and rebirth recur in their works. Films from the period 1946–66 as diverse as Maya Deren's Meshes of the Afternoon, Kenneth Anger's Fireworks, Maclaine's The End, Brakhage's Anticipation of the Night, Markopoulos's Twice a Man, and Bruce Baillie's Mass, are all, in different ways, films about the question of whether life — the filmmaker's own life, or human life in general — can continue to exist on this planet, and, if so, in what form and at what cost. In order to make films out of such alienation and about such themes, each filmmaker had, with only scant help from each other and from a European avant-garde tradition long since dead, to reinvent cinema. In doing so, each artist was, however unconsciously, retravelling a road many earlier American artists (Whitman and Ives, to name only two) had travelled before: the artist as reinventor of his medium; the artist as the pioneer come to carve out his own artistic space in a medium being reconceived of as new; the artist as a kind of Adam. The result was an extraordinary body of works which pushed cinema, the viewer, and the whole question of human existence to their very limits. Each work rearranged the pieces of the filmed world in a way not conceived of before, as if to remake the known facts of the world into a new system of knowledge, and a new set of rules about the ways in which one can know something. While each filmmaker was being nothing if not "personal," and while many of their energies stemmed from the most individually urgent of concerns (Fireworks and Twice a Man being, in very different ways, gay coming-out films, with coming-out cast as a form of death and rebirth), the dimensions onto which these concerns were projected were invariably much larger than the question of an individual human life. Stan Brakhage's Anticipation of the Night, for instance, is nothing if not a suicide film. The filmmaker who stands behind the expressionistically careening camera is desperately seeking involvement, engagement, with the visible world, and yet the repetitive, frequently sideways nature of the camera movements are the traces of a quest that has failed: the individual remains apart. The spatial isolation that appears near the film's end as a kind of summing up of all its spaces, leads inevitably to the final suicide. Having posited the question of the individual's relation to the world in one way — viz., that a successful relationship is a kind of all-or-nothing proposition, attained only through positive, penetrating involvement with seen things, and having taken the possibility of a failed relationship to its furthest possible extreme — Brakhage freed himself to ask again the question in different contexts and to come to other, less unitary conclusions in his later work. Indeed, each filmmaker re-asked for himself the question of what it means to live in the world, and in endeavoring to answer this question, made works which were themselves, in their complexity and completeness, varied attempts at answers.

These are the characteristics, more than any others, that I believe give the American avant-garde film movement its central significance. The urgency of the questions that each filmmaker asked, and the hugeness of the canvas on which they chose to provide their answer, created a cinema which, more than any other I know, can address the most urgent questions that an individual may have about himself and the society around him. That these works looked utterly different from the relatively homogeneous products of the mass culture of the initial two postwar decades goes without saying, but, in seeking to question those most basic values — such as the very possibility of human life, which the larger society took for granted — they were also ethically, socially, and even politically challenging to the society as a whole.

Sequence of frames from Dog Star Man: Part IV, by Stan Brakhage (1964). Courtesy of the Estate of Stan Brakhage and Fred Camper.

III

A wild bird during the season

Sings sweet lines in a fine style.

I do not praise a singer who shouts loudly:

Loud shouting does not make good singing,

But with smooth and sweet melody

Lovely singing is produced and this requires skill.

Few people possess it, but all set up as masters

And compose ballads, madrigals, and motets;

All try to outdo Phillippe and Marchettus,

Thus the country is so full of petty masters

That there is no room left for pupils.

— Jacopo da Bologna, c. 1340

Among the first American avant-garde films in the tradition that led finally to the movement we are discussing are the early works of Harry Smith and Christopher Young of the late 1930s, and Dwinnell Grant's and Maya Deren's of the early 1940s. But it was not until the years immediately after World War II that public screenings occurred with any frequency or that filmmakers began to make real contact with each other. One might therefore date the beginnings of this movement as a movement from 1946, just after the end of World War II, when Sidney Peterson and James Broughton collaborated on their first film, The Potted Psalm. The founding of Millennium Film Workshop in 1966, then, would occur precisely at the mid-point between the coalescence of this kind of filmmaking into a movement and the present day. At about the same time that Millennium was founded, an event of even more lasting import for the movement occurred: Markopoulos was hired to teach filmmaking in a midwestern art school. Though other filmmakers had taught avant-garde film before, Peterson among them, these were largely filmmakers who were themselves learning while teaching, and none of their positions lasted for very long. Markopoulos himself did not last out the school year and left the U.S. shortly thereafter, probably to his great advantage as an artist. Since his hiring, however, the movement of avant-garde filmmakers into the schools has been continuous and has for some time now been nearly complete.

It was also at the movement's mid-point, the mid to late 1960s, that American avant-garde film had its greatest social impact. The conformity of the ‘50s had been swept away by the extraordinary explosion of political protest, “counter-cultural” manifestations of all sorts, and a wide variety of eccentric individualism now known as the "late '60s." This period also coincided, not at all coincidentally, with the euphoria that accompanied a major topping-out of the nearly continuous two decades of U.S. economic expansion and prosperity that followed World War II.

As word of the movement spread, an increasingly adventurous and open-minded public flocked to these new “underground movies." A few, such as Anger's Scorpio Rising and Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls, even had extended runs in commercial theaters. Also, avant-garde films were perceived, often accurately, as being freer in the depiction of nudity and sexuality than the still relatively tame commercial cinema, and many viewers came hoping to see such things on the screen. For a relatively brief period, perhaps about 1965–1971, the avant-garde cinema seemed to have a significant, if small, social presence and cultural impact. Audiences at screenings would be diverse and varied; I recall one summer screening of “experimental” films by a college film society that was attended by upwards of six hundred people; that audience included undergraduates from the adjacent dorms, artsy types from the surrounding city, a variety of eccentrics, tourists in their shorts with cameras around their necks and children as well, two nuns in habit, and various persons of diverse appearance that would be difficult to categorize. Filmmakers supposedly as apolitical as Brakhage and Baillie, not unaware of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, would include references to war in their works, and would seek showings in the hope of having some impact, however indirect, on the debate surrounding the war. At the same time, these filmmakers conceived of their whole filmmaking activity as part of a broad attempt to change society. Such ambitions are of course consistent with the large scope, the huge canvas, that the masterpieces of this movement have always occupied: when one's very subject is human existence, in all its ramifications, it doesn't take that much further of a leap to hope that one of one's films might play a role in saving the world.

In the first two decades of this movement, then, filmmakers generally worked outside of any institutional structure. There were few or no grants available, few teaching jobs, and few exhibition opportunities. Filmmakers were in contact with one another, but no one had much money or influence, so the mutual support they could offer was of a spiritual rather than material kind. The years 1946–66 might well be called the “individual period” of American avant-garde filmmaking.

If the individual period was characterized by eccentric, highly original films made by the “founding filmmakers” arguing with American society as it was (and in so doing having an increasingly radical social impact, if only in the way that existing assumptions were challenged), then the second two decades have been in many ways a period of diminution: diminution of audience, of ambitions, of the quality of the work of newer filmmakers, of overall social impact. None of this is to say that there are not great films still being made (because there are), or that the movement does not still have significance, or that I might not be wrong in some of my negative judgments of some films. In setting forth the ways in which I find the movement diminished, I hope to open discussion, not close it, and to enrich the independent mode of filmmaking by challenging all its practitioners either to convince themselves I am wrong in my judgments or to improve the quality of their own work.

As noted, the central event of the movement's last twenty years has been the movement of filmmakers into the schools, as teachers of filmmaking and film history, and as students. Similarly, filmmaking grants have become more available, and exhibition possibilities, often in institutions supported by government funding, are greatly increased. The years from 1966 until the present might be called the institutional period of American avant-garde film.

Let me be clear that I do not perceive this as an entirely negative shift. Established filmmakers have been given some measure of economic security, at least in some cases, although it must be added that I know of no major filmmaker whose cinematic productivity actually increased after he commenced teaching, the opposite is true in many cases. In the early years of avant-garde fiIm such works were rarely screened outside major cities, so that it would be unlikely for a young person to be exposed to this work, as I was, via a public screening. Now, students in cities as diverse as Binghamton, New York, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, can, at age eighteen, view a wide variety of work that they might not have otherwise seen, and find, as I did, their lives permanently changed. It is true that there is a difference between going to see a film on one's own and seeing it in a classroom, but the interested student can often learn to let this difference affect him only minimally.

Still, it is to the shift into the schools that much of the change in the movement can be traced. If going to an avant-garde fiIm in the initial decades was itself an adventure, trying to make one was even more of a challenge. There were no thorough guides to the techniques of independent filmmaking; no manuals on lighting, or splicing, that would be useful to a person with limited means. Many people are intimidated by mechanical equipment, and the schools have done a service in that the access and instruction they provide has made it possible for many to make films who would not otherwise have done so. It is important, too, to remember that whether a completed film is successful or not, the act of making it can be an invaluable learning experience for the filmmaker. The fact remains, however, that the difficulty in seeing, exhibiting, and especially making avant-garde films in the initial years helped ensure that anyone involved with the movement was involved out of urgent personal necessity. This of course does not mean that no bad films were made; there were many. As is true of virtually all movements and periods, most of the work was far less than great. But given the personal expense and difficulty involved in making a film, few undertook it unless they felt it was something they urgently had to do, and that, I believe, accounts for the relatively high proportion of great films to bad ones in the individual period.

Today, a would-be filmmaker can enroll in any one of a number of college courses or less formal workshops, where he will receive ready access to equipment, instruction in its use, see screenings of selected independent films, and receive, whether he wishes to or not, the instructor's aesthetic biases. His fellow film students naturally and appropriately show sympathetic interest in and encouragement for each others' early efforts, as does, in most cases, the instructor. This is fine for a beginner, but often even as the student grows more advanced he will receive little or no negative comments on his work. Some avant-garde film faculty members indeed frown on such criticism, while others may offer it in such an extreme and eccentric form that the student finds it useless. Then, when the student graduates, he will seek out public screenings for his work, and some are embittered that they don't find the same caring sympathetic audience that existed among members of the school community. But blind encouragement is precisely the thing that will contribute to the rising number of mediocre and derivative filmmakers clamoring for attention and believing they are deserving of it. A curious shift has occurred, in which a movement that began by challenging, through its revolutionary practice, existing cinematic standards, now seems to operate at times as if there are no standards, as if every filmmaker is deserving of attention, and as if curators should exhibit the work of almost all comers:

…when the opportunities to exhibit are few and far between (as is the case today for many filmmakers) it becomes important, in my opinion, for curators to temper programming judgments with a spirit of knowledgeable, deliberate generosity, one in which the viewers are allowed to judge for themselves which films are vital and interesting, and which ones are not.

(Willie Varela, Spiral 2)

More urgent than the above concerns, though, is the difference between learning filmmaking technique for oneself and learning it in a school. To my mind, the best instruction book by far for the would-be avant-garde filmmaker is Stan Brakhage's A Moving Picture Giving and Taking Book. Yet this book, and its approach, is little known and little used even in schools purporting to teach avant-garde film making. Brakhage inveighs against the light meter, for instance, urging the filmmaker to learn to set exposure by eye, an approach virtually never followed in schools. Brakhage's whole attitude, which is that there is no single technique, no single exposure, no single light-setting that is correct, and that all are alive with visionary possibilities, including of course many that would be considered mistakes by established standards, has given way to less eccentric, more traditional methods, in which students are likely to be taught film technique through specific individual and class exercises and assignments. That fewer and fewer filmmakers are seeming to break new ground is perhaps attributable in part to the vastness and variety of cinematic achievements up until now, but it is difficult to believe that the kind of training they receive is not in some cases hampering their imaginative development in the very years when it is likely to be most fertile.

I am not here arguing against the teaching of traditional techniques, only pointing out that such training is inimical to the notion of making an “avant-garde” film, unless the training is in fact so comprehensive and thorough as to provide the student with a whole system both to learn and rebel against, which in most cases it is not, since in any event most avant-garde filmmakers do not know enough traditional techniques to provide such a course. When one has to discover how to handle a camera for oneself, there is more of a chance of developing an original grammar of camera-subject relationships than when one is trained in "how to do it" with a series of exercises. Indeed, Jonas Mekas has given a wonderful short talk in which he details the technical innovations in avant-garde cinema that have sprung out of equipment malfunction or filmmaker error. Of course, the filmmaker's genius is not in making the mistake, but in seeing how it can be used, what meaning it can be given in a film as a whole; but one is less likely to stray from the beaten path or to recognize a mistake once it is made as something worth using if one is trained in the “correct” methods.

Most importantly, the question of technique, for an avant-garde filmmaker, should not be separated out from the potentially chaotic realms of the imagination and the subconscious, in the way that teaching it thoroughly inevitably must do. To learn to make films without a light meter, and with Brakhage's book as a guide, is to come to understand that — if the work is to be vital, original, and alive — questions of f/stop, hand-held camera or tripod mounting, film stock, editing methods, and even the type of camera and splicer used, have emotional and ethical dimensions, and must ultimately be made instinctively, as a poet might choose words or phrases: with all manner of thought going into the choices except for the kind of calculation one would derive from a filmmaking manual or a grammar book. A talented film student might eventually see past the technical facts taught in a school to this more fundamental principle, and with practice, reach the desired state of filmic fluency. One can also understand how the teaching of avant-garde film technique (an oxymoronic phrase in itself!) is also a recipe for the end of avant-garde film.

The use of technique for the presentation of paradox, and the presentation of technique itself as paradox (as effected in some of the earlier masterworks described above), seems in fact most likely to evolve from a filmmaking practice that is either still in the process of its own self-discovery or has become so much a second-nature to its maker's own eccentricities as to be inseparable from the paradoxes of consciousness. The teaching of technique, by contrast, generally implies a model for filmmaking in which one makes a series of separate choices — as in, “I see such and such images in my mind's eye; how can I produce them on film?” While many filmmakers may work this way to some extent, the vital ones seem to me most likely to allow for an interdependent process in which the making of the film will affect how it looks, whereas an academic will go about the making as a series of discrete choices. This latter method may in fact be not inappropriate to some aspects of classical narrative or studio filmmaking, in which the mode of representation is relatively fixed, but it seems clearly inimical to the avant-garde tradition, for the utter refusal to present the materials of film as separate from the processes of human thought has been crucial to this movement's achievement.

The academicization and institutionalization of American avant-garde film is an extraordinarily ironic phenomenon. A movement that took a strongly adversarial position toward mainstream America has been, to use a '60s word that has long since gone out of fashion, “co-opted” by the culture as a whole, and especially by its dollars. The very notion of teaching “avant-garde” or “experimental” filmmaking in accredited colleges and universities is itself deeply ironic. Well-known filmmakers have in some cases more financial security than they did before in the form of permanent teaching jobs and other grants, but at the same time they have nowhere near the financial security needed to freely practice their art in the way a successful painter would. Thus, they are tied ever more closely to the world of teaching jobs, grants, and lecture tours. Sadly, these increased opportunities have not been accompanied by a greater social impact for the work. In fact, avant-garde film has, for the first time since its inception as a movement, almost no impact on the culture as a whole. The public audience for the work has fallen off drastically. Indeed, I have been to more than one public screening in which the audience of ten or so consists of friends of the filmmaker, so that the questions are all along the lines of, “Last year, when you showed me that second film in your loft…"

Perhaps in part because of the co-opting, the movement has lost much of its adversarial thrust. The majority of filmmakers still view the mass-culture negatively, but often through so many levels of irony that it is difficult to know what the filmmaker's position actually is. For instance, in James Benning's long-take film, 9/1/75, his camera moves around a family campground; the sounds of radios and children are heard. The audience is encouraged to view this scene humorously, but it is unclear if the filmmaker, while obviously amused, is taking any specific position concerning his subject-matter. The technique Benning uses here is commonly used by many younger filmmakers and students. Many subjects can be rendered amusing, even absurd, simply through the act of recording them on film. This is a relatively easy form of irony to achieve; it lacks inner complexity and it tells us little about the subject or the filmmaker's relation to it. Indeed, it is tempting to suggest that a form of narcissism lurks behind it; that the subject of the film has been shifted, and has no relation to what is actually depicted but rather only to the filmmaker's feeling pleased at his image's ironic superiority to the objects his film contains. That this is often the case is supported by the fact that this simple irony-through-imaging has a consistent quality for the viewer regardless of the subject-matter.

Irony is indeed a key aspect of much student work, and it is not hard to understand how a television-bred generation has difficulty regarding any image as possessing the authentic incantatory force that the images of the great founding films are meant to have. The figure on the pavement in Bruce Baillie's Mass, the shadow man in Anticipation of the Night, the protagonist in Meshes of the Afternoon, the beatnik-absurd suicides in The End, are all authentic figures whose images speak as clearly and directly as any avant-garde film steeped in the ambiguities of modernism is able to do. Even the figures of Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, with their absurdly exaggerated costumes and colors, are, for all of Anger's innate sense of self-parody, also possessed with some small fragment of the power of an icon. When one compares much of Benning's work to these, or to the first two films of Ron Rice, The Flower Thief and Senseless, which also view the American landscape, one is struck by the eccentricity, authenticity, and inner complexity of the work of the earlier masters. In Rice's case, we have filmmaking on the edge: filmmaking at the limits of existence: marginal filmmaking whose critical voice vis-à-vis mainstream values is authenticated in part by the fact that the filmmaker himself is living an utterly marginal existence, making his films from a position of extreme alienation. Senseless, in particular, is one of those rare masterpieces that succeeds because of the way in which its parts are always pulling away from each other, because of the way in which the film, in a near-crazed state, seems forever on the brink of its own annihilation. If one then turns from this cinema-at-its-limit back to Benning, the differences become clearer, and it even becomes possible to be confused about whether Benning is being ironic at all, or whether he is simply filming things that he likes because he enjoys seeing them on the screen.

An amusing way of limning the contrast further between the founding filmmaker Ron Rice and the more subdued and academic Benning is to compare two very similar letters they wrote. Both letters belong to a subgenre of American avant-garde film correspondence, viz., the letter in which one seeks financing for one's film. Here is Rice writing, presumably out of the blue, to the then-big-time movie producer Joseph E. Levine (whose name he misspells as “Levene”), in 1962:

…I humbly submit myself to your judgement. But, and remember this well, Mr, magnet, ONLY ONCE, NOW OR NEVER do you make a move to underwrite a MOTION PICTURE FILM OF LASTING VALUE.

Or you will GO DOWN IN FLAMES. If you do not financially support my NEW FILM, then I shall direct all the efforts of my ELABORATE, staff to THE COMPLETE ANILATION OF YHOUR ORGANIZATION including Sophia Loren and all the other BIG TITS you have in your stable. And while I'm 'at it' I might also DESTROY the two publications, TIME and LIFE who's Brain-networks occupy the same STRUCTURE from which you sell TIT….

(Film Culture 39, Winter 1965; all spelling and grammar as in the original)

Now here is James Benning, writing twenty-one years later to the President of the Sands Hotel and Casino:

In the spirit of Reaganomics I beg for your help. But don't get me wrong, money for the Arts has always been tight in this country: I don't mean to belittle the President, but only wish to follow his advice to seek money from the private sector. I can offer you a sure $50,000 tax loss, if you invest that amount in my next film. I must stress that none of my films have made any real profit. This is a risk FREE investment. Please send the money as soon as possible, so we can both thank Mr. Reagan. (ldeolects 13)

The differences here are striking, but chief among them is the fact that it seems possible that, in whatever state he was in, Ron Rice believed that his letter might actually work. (He continues in a comparatively calmer tone, apologizing for getting "carried away" and providing details as to the film he wishes to make and the steps Mr. "Levene" should take to produce it.) But whatever Rice may have believed, his letter has the quality of the authentic cri de cœur, the desperate and authentic voice that knows the rightness of its own extreme anguish. Rice also takes the trouble to note that Levine's corporate offices are in the Time-Life building, and therefore he includes an attack on those then-bastions of American mass-culture, Time and Life magazines, as well as on Levine himself, seeing all mass-culture as being connected and feeling the necessity to express his utter contempt for it. Benning, by contrast, seems to have written his letter entirely as a joke, knowing that it would not succeed, and yet at the same time displaying absolutely no hostility toward the president of the casino. (Actually, in soliciting letters for their journal, the editors of the ldeolects letters issue, in which Benning's epistle appeared, encouraged filmmakers to write letters specifically for that issue if they did not have already-written letters that they felt were appropriate for publication.)

Of course to merely show that a movement has changed is not to prove that it is also diminished. The reader is free to accept aspects of my description without accepting my particular value judgments. In chronicling this change, and in expressing my own preferences, I also must acknowledge that it is not possible to turn back the clock. American society itself has changed; the mass culture has become more diverse; the society has become more tolerant of differences. A body of completed avant-garde films ensures that newer filmmakers will find it difficult to break new cinematic ground. All are now working within an established tradition. Further, there is no reason to expect or require that a movement's later period will continue the earlier one, or that it should be judged by the standards of earlier filmmaking. American avant-garde cinema has branched out into a variety of new directions, all of them healthy developments if only by virtue of the fact that variety within a movement should always, in the absence of any convincing evidence to the contrary, be counted as positive. My problem is that, in my judgment, the works of the newer generation of filmmakers for the most part lack the authentic power of the original (often still-active) masters, and that the qualities that they do have instead often seem related to, but also only as diminished shadows of, the achievements of the original filmmakers. But the reader is asked to understand that my writing here is intentionally polemical, and that in stating my case as strongly as I can, I also hope to elicit arguments pointing to what I am missing.

IV

It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academicism. There is no such thing as a good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless.

— Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb

Some years ago, an acquaintance of mine who was teaching filmmaking in a major university, whose film department encouraged avant-garde filmmaking as one possibility, told me he had a student who announced that he was making a film that would be "just like" Serene Velocity, but that instead of a corridor he was using a different space. In other words, he would be applying Gehr's technique of rapid alternation of images of different focal lengths of the same scene to a space other than the corridor for which that technique was originally developed. The problems of such a venture should be apparent to anyone who understands filmmaking. Technique does not exist in itself, but it is always seen by the viewer only in relation to what is shown. The "techniques" of Serene Velocity were tied to the particular space that Gehr was filming, and to the particular qualities he wanted to impart to that space. Anyone who understands this film would be unlikely to try to apply that technique to a different space without a specific reason for doing so.

One quality of academic art is that it avoids reflecting the complexities, the contradictions, the violent impulses of a life lived with passion, in favor of the airless repetition of the techniques of past art. These techniques are rendered partial; they are drained of life in this repetition; they are stripped of the connection to an outer reality that occasioned their presence in the works that first used them. In Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey's co-directed feature-length films, each scene is shot in a single take, generally with the camera relatively distant from the subject matter. When queried, at a screening of their film Crystal Gazing, as to the reason for this technique, Wollen replied that, while this method of filming was easier and cheaper and they were experienced in it, their "real" reason for using it was a Brechtian one: to prevent a naive, escapist involvement with the material on the screen. Sadly, there is little in the wooden, near-lifeless automatons that pass for characters in this film which would be likely to produce such involvement to begin with. Brecht's alienation effect depends on his dramatic skill and a performing company's theatrical and acting skills to create wonderfully human, compelling, complex, humorous, and self-contradictory characters — which he would then proceed to alienate the audience from. One cannot have a meaningful alienation without some involvement, for then there is no dialectic. Mother Courage, where are you when we need you?

It is perhaps no accident that Wollen began making films himself only after writing criticism and teaching film. To be sure, this is hardly a dishonorable route into filmmaking. But if one compares Wollen's carefully-argued and purportedly logical Signs and Meaning in Cinema with, for example, Jean-Luc Godard's idiosyncratic and gnomic Cahiers du Cinema reviews, one sees a world of difference. It should be said, too, that Wollen is by no means the only avant-garde filmmaker who began making films after getting his first film teaching job. Aside from whatever implications one may wish to draw — or reject — as to the kind of work likely to emerge from such a progression, it is surely a further irony to see that the movement by artists who had begun making films in the individual period, into teaching during the early institutional period, has-completely reversed its direction, at least in some cases, with a beginning in teaching then leading into filmmaking.

The teaching of film as it is usually practiced in the U.S. — the teaching of art-making to students who often don't know what they want to do — itself encourages what Rothko and Gottlieb call “academicism.” One assigns exercises, one assigns the making of specific films. The student may not know what to make a film about, but has to make something in order to get credit for “Filmmaking I.” The instructor may even assign the subject-matter. Once, when I myself was teaching filmmaking in an art school, a student felt I had deeply offended him when I responded to his complaint that he didn't know what to make films about by suggesting that he take some time off to travel or work at a job. There is no reason why assignments and exercises might not lead a student to make films about subjects which are vital to him, but there is something about the way schools function that can discourage students from confronting the essential problem. All too often the student feels that the school's primary purpose is to offer him support and positive reinforcement, and the school itself does nothing to discourage that attitude. Past cinema achievements are not used here as a challenge, or a club, but rather as a call, a call asking that new work at least aspire to the levels already reached. This is unlikely to happen when the attitude taken toward filmmaking is a casual one, or when the making of a film is seen as an assignment similar to other assignments for other classes.

The question of whether a film is “academic” does not, however, depend on whether it was made in a school. I would prefer to think of academicism as a way of describing a work that is characterized by certain qualities. In an "academic" film, the cinematic devices do not seem to have a vital, authentic reason for being. Such devices, often borrowed from other films, are academic when they become mannerisms in Ezra Pound's sense of the word: stylistic elements that have divorced themselves from meaning. It is easy to see how the school situation, in which technical exercises might be given to help the student learn the medium but without any other reason for being done, would encourage "academic" work, but a different student might see such exercises for what they are, and later learn to make authentic works of their own. There is, of course, a long and venerable tradition in other arts, such as painting and music, of students doing years of imitative exercises; the best will later find their own paths to greatness, doubtless aided by the training they have received. My purpose here is not to attack the teaching of avant-garde filmmaking in schools, which was an inevitable movement anyway and now cannot be reversed, but rather to suggest some of the dangers inherent therein.

Just as the movement into the schools cannot be reversed, so we should not expect a return to the original, “authentic madman” period of American avant-garde filmmaking, nor am I calling for that. We live in a different era. The culture itself has become far more accommodating of diversity. Avant-garde filmmaking is itself now a tradition which new filmmakers have to face. After decades in which filmmakers tended to work in distinct and separate styles, in which for instance there would be no mistaking an Anger for a Brakhage, or a Frampton for a Gehr, a new eclecticism has emerged. Linear dramatic narrative is a more frequently-explored possibility, often in combination with more traditionally avant-garde modes. It is only natural that the movement's initial sharp and narrowly-directed thrust would become broadened out as it has, and if it seems to have lost some of its focus as a movement that is due in part to this new diversity. But there is a fine line between a movement that has lost its focus and a movement that has died, and we must consider whether it makes sense to claim a living “avant-garde.” What is alive is the tradition of the personally made film, a tradition initiated by the original avant-gardists, and there is every reason to believe that new advances in the medium will result from this mode of working. But it must be acknowledged that a mode of working is not a movement.

Meanwhile, it is very hard for the interested observer to keep track of whatever it is that is happening. So many films are being made that it is impossible for anyone to keep up. I always hope that there are great new filmmakers working whose films I have simply not been able to see, and that articles such as this will encourage others to make viewing suggestions

for us all. If there is a complaint here, it is that many curators follow Willie Varela's advice more than he cares to admit: that venues of avant-garde film often give shows to filmmakers in whom even the curator himself does not believe very strongly because "so-and-so" deserves a show at this point in his or her career. In the hope of discovering that there is more there than visible to me at first, I am always willing to sit through work I don't initially care for if someone else believes in it strongly. However, life is too short and the diversity of cultural offerings present in any large city is too great for one to wish to spend much time viewing films that not only look like terrible works but which the programmer himself won't even defend. Such spectacles can hardly help the movement with the small public audience that does remain for it, either. Worse, the filmmaker of such films often does not even believe in them very strongly himself, nor does he appear to have a very vital purpose for having made them. The call for subject matter that is tragic and timeless still holds if one construes it broadly enough: there must be a large, rather than a small, reason for making a film, and that reason must be tied to some notion of the film's relationship to the world. To say that one enjoys working with film, or likes the way a certain editing pattern looks on the screen, is not enough. If one reads the interviews with and articles by the founding filmmakers, one finds, in the writings and statements of artists as diverse as Deren, Brakhage, Jack Smith, Harry Smith, Breer, Gehr, and Frampton, a sense of the possibility of film for achievements on a grand scale. While it is wrong to assume that a filmmaker's writing reflects the worth of his films, it is of interest that in many cases the founding filmmakers make arguments for cinema's possibilities, for a reformulation of experience in grand terms, in a manner that is consistent with their cinematic achievements. By contrast, one of my complaints about much newer work is that, whether successful or not, it doesn't seem to be attempting to do very much at all. This, too, is often reflected in the statements of some newer filmmakers, which at times seem to be replacing the aesthetic and moral assertions of an earlier generation with the simple assertion, by each filmmaker, of his own self-importance. The canvas has shrunk, the battlefield's scale is diminished, from questions of human consciousness and the individual's place in society to narrower questions of, for instance, a filmmaker claiming to like particular shapes, colors, and rhythms, and wishing to reproduce them on the screen. Some years ago, a filmmaker who showed me his films met my comment that their editing was very erratic and nervous with "I'm a very nervous guy," said with a mixture of aggressiveness and defensiveness that made it clear that he identified his film style with his person and that "my film is me" was being used as a kind of validation of the work.

None of this is to say that many bad filmmakers don't also have grand ambitions for their work. Also, it is hopelessly self-destructive, when trying to make a film, to try to make something great. One can often reach a large goal by thinking in the smallest of terms.

Sequence of frames from Dog Star Man: Prelude, by Stan Brakhage (1961). Courtesy of the Estate of Stan Brakhage and Fred Camper.

Sequence of frames from Lemon by Hollis Frampton (1969).

V

Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure in perception. How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of 'Green'?

— Stan Brakhage

While there have certainly been many periods in which artists have willingly banded together, formed a movement, and chosen a name for themselves, there is a counter-tradition, especially strong in America, of artists resisting labels of any kind. Each artist feels he is unique, and has reinvented his medium for himself. The American avant-garde film movement, in particular, has always had a crisis over the issue of naming, whether in applying language to an element within one's film, in naming some phase or sub-genre of the movement, or in the naming of the movement as a whole.

In 1969, P. Adams Sitney published the article "Structural Film," in Film Culture 47, identifying certain tendencies he felt a number of diverse filmmakers had in common. Virtually every filmmaker named in the article has objected to this labelling, some in interviews (“...I dislike labels. They stop people from actually seeing, experiencing the work." — Ernie Gehr), others in their films (see, for instance, George Landow's hilarious parody of the "structural film" in Wide Angle Saxon). These objections are not a bit surprising, given the movement's character. What did surprise me was the emergence, a few years after Sitney's article, of a newer generation of filmmakers, in both the U.S. and Britain, who were not at all uncomfortable with using the label "structural" to describe their work, or who even constructed grander labels, such as Peter Gidal's “Structural/Materialist” film. Many of these films explored issues of cinematic representation, or of the medium's mechanism in a simple, logical, unparadoxical manner that can only be called academic. In a rich and unbroken chain of masterpieces stretching from Harry Smith to Yvonne Rainer, the question of the medium, its mechanics and its illusion, has always been present as one element of a work. Generally this element is presented as a question, or a series of questions, which cause the viewer to think about the nature of the medium and to reflect back also on the specific nature and themes of the film. Thus one asks: “Are those sailors in Fireworks really sailors? are they actors meant to be taken as sailors? are they meant to be seen as the filmmaker/protagonist's fantasy of sailors? are they meant to be seen as men who dress up as sailors for the sake of the film's particular fantasy?” Similarly, is the colored fan in Eaux d’Artifice meant to be seen in light of Méliès and silent film tinting, as a magical apparition, or as both?

In Fireworks, the sailors vibrate between each of these named possibilities. In Eaux d’Artifice, the single hand-tinted fan calls attention to the medium, to the film's very surface;

it also refers to Méliès; it is also a magical apparition best understood in terms of similar occurrences in other Anger films. In Brakhage’s Dog Star Man, the painting and scratching on film again refers to the surface, and to the frame-by-frame nature of projection; it also refers to closed-eye vision; it relates on the levels of rhythm, space, and often, metaphor, to the photo images being scratched or painted over, adding as well a variety of differing affective moods depending on the quality of paint and the nature of the material painted over. In Snow's La Région Centrale, the complex machine-controlled camera movements are tied to the nature of the specific landscape seen, to the idea of a trackless and boundless wilderness. In Rainer's Film About A Woman Who…, the printed titles call attention to themselves, but also have a deep emotional resonance in the film, both in terms of the specifics of the narrative and, more generally, in terms of the floating, hovering quality they have in the film's overall indeterminate space, signifying the uncertainties and ambivalences of the central character. The problem with the later academic structuralists is that their technique tends to become divorced from any content beyond the most mechanical, self-referential examination of the medium's properties. What had been present as a question, in these earlier films, a question tied to the inevitably human and emotional content of specific works, becomes returned as an answer. There is, then, a lack of respect for the viewer shown by such films. Rather than being asked, probed, addressed as a unique being, presented with conceptual and perceptual paradoxes to which he can respond as he wishes, the viewer is presented with ready-made answers; even, with instructions for how to see and how to think. The viewer, defined as a complex and emotional being by the masterwork, is defined as the recalcitrant and somewhat dull pupil in the academical structural films that sprouted up like weeds in the years following Sitney's article. While that article has been analyzed extensively and often attacked, its final prediction, that “In the next years we can expect…both inevitably a climax and a degeneration of the mode," came true with a vengeance.

It is indeed one of the great ironies of this phase of avant-garde film, an irony in many ways uncomfortably similar in form to others I have mentioned, that among these filmmakers there are many purporting to be politically progressive, who regarded the achievements of the earlier poetic filmmakers as reactionary and “crypto-fascist.” Yet, for this viewer at least, it is the later films of Malcolm LeGrice that treat the viewer as a mere object into which the film is to inject the proper attitude, while in the work of a Brakhage the viewer is constantly encouraged to think, to question, to argue with the film. Each film, indeed, implies a model of a viewer; each film, by its techniques, constructs the kind of individual that is needed to see it. It seems generally true that the more academic the film, the more simple-minded the implied viewer. Indeed, the particular manner in which the structural mode degenerated is characteristic of the way art-movements tend to degenerate, and bears some uncomfortable similarity to the emerging situation in avant-garde film today. Stylistic devices that had an emotional, intellectual, aesthetic and ethical life in the original works are repeated as mere shadows of their former selves, as empty gestures with, at best, one very small and not very interesting meaning. As has happened in other arts, in architecture, in fashion, formal elements that had an authentic life in the work have become presences used merely for appearance rather than for function.

It is worth remarking as well on the question of how one names the movement I have been calling American avant-garde film. In the early decades, everyone recognized the need to find a label that would tell the uninitiated that these were films very different from what was then customarily understood by the word "movie." Among the most commonly used appellations were “experimental,” “underground,” “avant-garde,” “'independent,” and "New American Cinema." Hardly anyone, least of all the filmmakers, was happy with any of those terms. “Experimental” was thought to be a term of derision; the filmmaker would respond to its use, “I needed to make some 'experiments' as part of my research in the making of this film, but I left those back in my editing room. What you see here is a fully realized and completed work." “Underground" had political and other connotations that many were unhappy with; "avant-garde" was a European term; "independent" too vague. (Disney, for instance, is an "independent" Hollywood studio.) Neologisms were proposed, such as “undependent,” meaning “not dependent"; few were happy with any term. While this unhappiness created problems for writers, publicists, and exhibitors of these works, I took it to be a sign of the authentic diverse energies of the movement, and its fundamentally anarchic nature. Now, in the institutional period, many filmmakers have emerged who are quite happy with one or another of those labels. There is, for instance, a group of filmmakers in Chicago, many of them also film academics or students at a local art school, which purports to be a national lobbying group, and which calls itself the “Experimental Film Coalition.” It is tempting to suggest that at the point that a sufficiently large group of filmmakers has decided that they are making “experimental” films, it is more than likely that their work is not, in any real sense, experimental. More generally, the settling down of the question of naming coincides with the institutionalization of the movement.

Sequence of frames from Naughts, by Stan Brakhage (1994). Courtesy of the Estate of Stan Brakhage and Fred Camper.

VI

You ask whether your verses are good. You ask me. You have asked others before. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems and you are disturbed when certain editors reject your efforts. Now (since you have allowed me to advise you) I beg you to give up all that. You are looking outward, and that above all you should not do now. Nobody can counsel and help you, nobody. There is only one single way. Go into yourself. Search for the reason that bids you to write; find out whether it is spreading out its roots in the deepest places of your heart, acknowledge to yourself whether you would have to die if it were denied you to write. This above all — ask yourself in the stillest hour of your night: must I write? Delve into yourself for a deep answer. And if this should be affirmative, if you may meet this earnest question with a strong and simple “I must,” then build your life according to this necessity; your life even unto its most indifferent and slightest hour must be a song of this urge and a testimony to it. Then draw near to nature. Then try, like some first human being, to say what you see and experience and love and lose.

— Rainer Maria Rilke

I have spent most of my career as a writer-on-film writing only about those films that I care most about, praising them, and trying to find descriptions of them that might open them for other viewers so that those viewers might share the ecstasies and meanings I have found in them. It always seemed very much to the point to speak about cinema at its best; it was, after all, the power of masterpieces that first attracted me to the medium, and that I still consider its foremost justification; a great film, or a film that is great in part, through its very greatness has pushed the medium to its limits. I can count the negative articles I have written on films on the fingers of one hand. But we have reached a point at which a movement that I care about more directly than any other in the history of the medium has reached a state of decadence so extreme that I feel I can no longer remain silent. It is because I care so much about this movement, because its masterpieces have given me so much, and because as a movement it has pushed cinema into a realm of purity and depth rare in any medium, that I continually go to works by lesser-known avant-garde filmmakers, always trying to stay in touch with current work. I don't mind seeing work I don't care for; what I do object to is having an evening that was set aside in the hope of finding something of even mild interest consumed by work so seemingly poor that it should not have been let out of the classroom, so demonstrably disorganized or obviously unoriginal that it has little reason for a public life at all, and then find that the work's supposed defenders, the filmmaker, or the curator who programmed it, have arguments for it so narrow as to confirm my own reaction, or worse, arguments that are virtually nonexistent. Few who try will succeed in making a great film, and it is hardly a dishonor to fail. There can in fact be many reasons for making a film. One may learn self-discipline. The act of trying to make a truly “personal” film may help one understand, for oneself, one's own subjective way of perceiving the world. Such awareness, gained through long hours behind the camera and at the editing-table, can doubtless be valuable, and one defense of teaching filmmaking is precisely that: that whether the pupil makes a good film or not, if he tries hard he will learn about himself. But while such activities are of interest to the individual, his teachers, his friends, they are of only limited interest to the society as a whole. Do we really want "personal" filmmaking to become a branch of the human potential movement?

Those films that I call great I so name because of the depth to which they affect me. The filmmaker's sensibility is given an objective form through his control of the medium. That sensibility is not represented as a single note or chord but as a bundle of diverse, even conflicting impulses and ideas. The work also achieves an intensity, a searing beauty, which is ultimately ecstatic in the specific sense that it takes one out of oneself, and allows the viewer to see the cosmos of another. At the same time, one never is permitted to forget that the film's aesthetics are inseparable from its ethics; that the film is also an expression of ideas; that its scale is huge enough to be taking a position about what it means to be alive in this world. One may of course vehemently disagree with the position and still admire the film: I find Riefenstahl's Triumph Of The Will at least as valuable as an objective history because it renders fascism both visible and beautiful, allowing me to see even the tiniest of such impulses as they reside in me. This is not to say that work I feel is bad should not be shown: indeed, we do not want an utterly closed exhibition situation. I only ask that for every film that is shown there be someone who really believes in its value, who feels it is a work that is capable of having some sort of dialog with those works that have, through their own greatness, defined our medium.

It is time, then, and with real regrets, to speak of some bad films. I must preface these remarks by saying that since I believe that what makes a film great is ultimately mysterious, I can never be sure that I am correct in calling a film “bad,” can never be sure that at some later date, on re-viewing, perhaps in the light of the filmmaker's later work, I might not change my mind about a particular film. Nonetheless, I wish to speak of what I have seen. The four filmmakers mentioned below are not, in my opinion, unusually poor artists; they all appear to be honest and sincere people who are doing the best work they can at the moment. Each is technically skilled to the degree that one can assume that their films look roughly as they wish them to look. Each is chosen for illustrating a particular tendency present in the movement.

One of my complaints, already mentioned, about recent work is that the focus or scale of the subject-matter has narrowed. The films of Holly Fisher explore the vocabulary of home optical printing, and attempt to produce a cinematic organization out of color and shape. Of course, there is nothing wrong with this in itself; art that is "about” a great deal can develop from abstract materials. In one of her answers to a question about how her films are organized, she talked of her attention to the color scheme of the overall work, in terms of achieving a balance between the colors. In answer to another question, she described her working method as beginning with the shooting of 8mm travel movies on trips she takes with her husband, after which “I throw them on my optical printer, and utilize a combination of improvisation and chance operations.” It disturbed me to see that her description seemed to match what the films looked Iike so perfectly, to the point where I might have imagined the films from her description, a frequent sign of academicism. (I defy anyone to read one of Brakhage's descriptions of a film of his, and accurately predict what the film will look like.) Even more importantly, I could find nothing, either in Fisher's talk or most significantly in the films, to suggest that they were about anything outside of their own physical qualities and technique.

Dan Curry has made a number of films, all technically accomplished, many humorous. While he personally may reject the label, I see him as an example of the later generation of academic structural filmmakers described above. His films all seem to repeat, on a lesser level, certain aspects of the achievements of earlier filmmakers. Of course no two films are alike, any more than any two fingerprints are alike, but it is one of the myths of personal filmmaking in America that the mere fact of each person's and each work's difference guarantees that the work will itself be of interest. There are differences that reflect an originality of thought, and there are differences that are merely superficial variations in appearance and tone. No two fingerprints are exactly alike, but enough fingerprints follow similar patterns so that few would want to spend their lives studying the small differences between each.

Curry's Primer Rebus is a fairly long film, using pictures, rebus-fashion, to stand for words. It has some of the imposing quality of Zorns Lemma, though in seeking equivalents between word and picture, Curry seeks identities between word and image while Frampton

had sought disparities and paradoxes. Indeed, one of the shifts that has occurred in the movement is a move away from the radically disjunctive, the paradoxical, toward the linear and the mimetic. At the end of Primer Rebus, the filmmaker presents a long “dictionary,” in which each picture that he used is accompanied on the soundtrack by the word that it represented. During this section, strains of a Bach Brandenburg Concerto fade up on the soundtrack and are mixed into the voice. When questioned as to why he had done this, Curry replied that he did it to “soften” the film; that he was concerned about questions of audience “consumption”: in other words, he didn't want his viewers to get bored. This is an issue that would have been unlikely to have occurred at all to an earlier generation of filmmakers, or if it did, it would have been raised in its negative formulation, as in, "Oh, so they say they're bored? Well, we'II do something to make them really bored!" (Some years ago, an irate Village Voice reader wrote to protest Jonas Mekas' favorable reviews of what the reader called "Andy Warhol's two-hour films of Taylor Mead's ass." Taylor Mead wrote in reply that he and Andy had searched through Warhol's oeuvre and were unable to find any such work, so they were proceeding to make one.) Indeed, it is precisely the way in which films like Zorns Lemma or La Région Centrale play with the viewer's temporal expectations that they do much of their work. By “softening" his film Curry has robbed it of any integrity that it might, even as a derivative work, have had. His justification for doing so is indeed another sign of a movement that has lost its direction. Since when has it been “avant-garde" or "experimental" to use background music for an image-and-language film when one is worried that the "audience" (note here Curry's "audience" versus earlier filmmakers'

"viewer" and "spectator") might get bored?

In this regard, I am reminded of the filmmaker Ted Lyman, who, at a showing of his films, said that while he admired the achievements of Brakhage and others, he thought that it was now time to incorporate their cinematic accomplishments into films that were accessible to a wider audience. While I personally think that how accessible a film is has virtually no relationship, positively or inversely, to its aesthetic value, the solution that Lyman chose in one of his films is a real reduction of the achievements of the avant-garde. In a black-and-white film about a boat trip, he inserts a red animated outlined figure, through whose eyes the trip was supposedly seen. The effect is, in his words, to “foreground" the issue of human subjectivity in film. But what makes Brakhage's work so profound in its exploration of this issue is his general exclusion, since Anticipation Of The Night, of such figures. Rather than having a surrogate protagonist with whom to identify, the viewer is given to understand that he sees through the filmmaker's eyes, and that he himself is the film's true subject; that it is the viewer's eyes that the film directly addresses. The insertion of a surrogate viewer into such a film is likely, as it did in Lyman's film, to distance the viewer from the work, and to deny the viewer the possibility of the kinds of complex, inter-subjective involvements that the experience of viewing such a work is at its best. Indeed, one of the deepest aspects of the works of Brakhage and others is that, for the viewer, one can never make an easy separation between the film's subjective system and one's own. The viewer is always forced to ask a series of questions of the work: "ls this the way the world itself is? Or is this the world as it appears only through the filmmaker's eyes? Is this the world as it appears, or could appear, to my eyes?" And of course, these questions are not asked as a series, but come all together, as a single connected nexus of thought. The academic filmmaking of a Ted Lyman is the sort of work that conceives of these questions as separate issues, and worse, seeks to provide answers. It is in such ways that the filmmaker indicates a lack of respect for, even a talking-down to, the viewer.

I must also confess that I care Iittle for that part of the human character that seeks to calculate what will appeal to others not known personally to the individual, and then attempts to alter or "soften" works in order to speak to them, and I fail to see how such calculations can be said to emanate from a particularly vital or deep aspect of the maker's being. Even the great classical Hollywood filmmakers, who were great audience-pleasers as well, rarely if ever engaged in calculations of this sort. Howard Hawks, for instance, always spoke of making films about the kind of people he liked, hoping that the audience would like them as welI.

The reader will observe a common theme emerging here: that the original sharpness and uniqueness of avant-garde cinema seems to be dissolving in a kind of indistinct haze, in which the degree of difference from the commercial mainstream, a difference that was in the past as good as any as a single-phrase description of an avant-garde film, seems to be lessening. That lessening was never clearer to me than in a recent screening of the films of Alan Berliner. In his newer works, Myth in the Electric Age, Natural History, and Everywhere at Once, he utilizes found footage, editing it in an often asynchronous combination with found sounds. The films are very well crafted, often energetic and surprising in their combinations, and sometimes amusing. In one shot, seeds fall to the ground in exact sync with musical notes coming from an unseen source. Oddly, though, the effect of these sync events is quite different from that of related events in, for instance, Peter Kubelka's Unsere Afrikareise. In the Kubelka film, a hat blown off of a head by the wind is accompanied by the sound of a gunshot, and one feels that the filmmaker has combined two elements that would not normally be seen together into a new entity, an entity which is also making a statement about the subject-matter. In Berliner's work, however asynchronous the combinations may seem, his skill in rhythmic matching and his particular brand of humor tends to produce an undisturbing smoothness of texture and tone. The films are surprisingly seamless in appearance, given how they were made. That seamlessness also means that the even flow Berliner creates prevents individual elements from standing out strongly enough to make specific statements. What emerges, then, is nothing so much as a series of jokes on the footage, jokes that rarely have a moral point. Whereas Kubelka refers to his sync events as “articulations," it is tempting to observe that Berliner's sync events are inarticulate in the particular sense that they lack strongly-expressed ideas, ideas that cut into the viewer's consciousness with the force of an edit filled with thought. Although the films themselves look very different from those of the commercial mainstream, in overall effect and ethics they seem to me indeed not very different from the television sitcom: he goes for whatever combination will produce a laugh, with relatively little attention to any overall coherence or theme other than the most obvious sort. In other words, I saw no real values being expressed, no real subject-matter, merely effects for their own sake, or for the sake of manipulating the audience.