Lamar Peterson’s Modernist Grimace

Most viewers, upon encountering Lamar Peterson’s work, will go no further than to subsume the paintings under the generic category of “black figuration.” This is to be expected; most people don’t care enough about art to actually look at it (whether they admit it to themselves or not). It is flat out embarrassing, however, when the supposed viewer par excellence — the art critic, from whom we viewers are supposed to learn to see — is revealed to be a sub-par viewer herself by failing to go beyond this superficial level.

Martha Schwendener’s recent review of Peterson’s show, The View from Outside at Fredericks and Freiser, is sub-par criticism par excellence. With the shapelessness characteristic of New York Times’ “art criticism,” Schwendener gestures at what passes for the criteria of artistic relevance today: being the first to work in a particular mode (as if being “way ahead of the curve in the recent Black figurative painting boom” had any bearing on the work’s success); referencing art history (as if “[harking] back to Manet’s landmark Luncheon on the Grass were enough to justify a painting’s existence); and a supposed subversion of the referenced history (as if merely “[suggesting] underlying emotional and psychological states” of black men . . . typically overlooked in Western painting,” were sufficient to subvert an already dead painting tradition). But it is the final sentence of her review that shows she has done worse than simply generalize the paintings, but has, rather, thoroughly failed to see them, to enter the world they create: “The narrative that grounds them is a life rooted in ritual — cooking, cleaning, watering the plants and painting — and the idea that, for ambitious painting, that may be a radical subject.” Schwendener is so mistaken that the opposite is true. It is precisely their lack of narrative, lack of grounding and “rootedness,” whether in ritual or soil, that realizes the world these black men inhabit: a static world of utter visibility, a world of paint that is all surface, where the passage of time and the existence of psychological interiority is impossible.

//

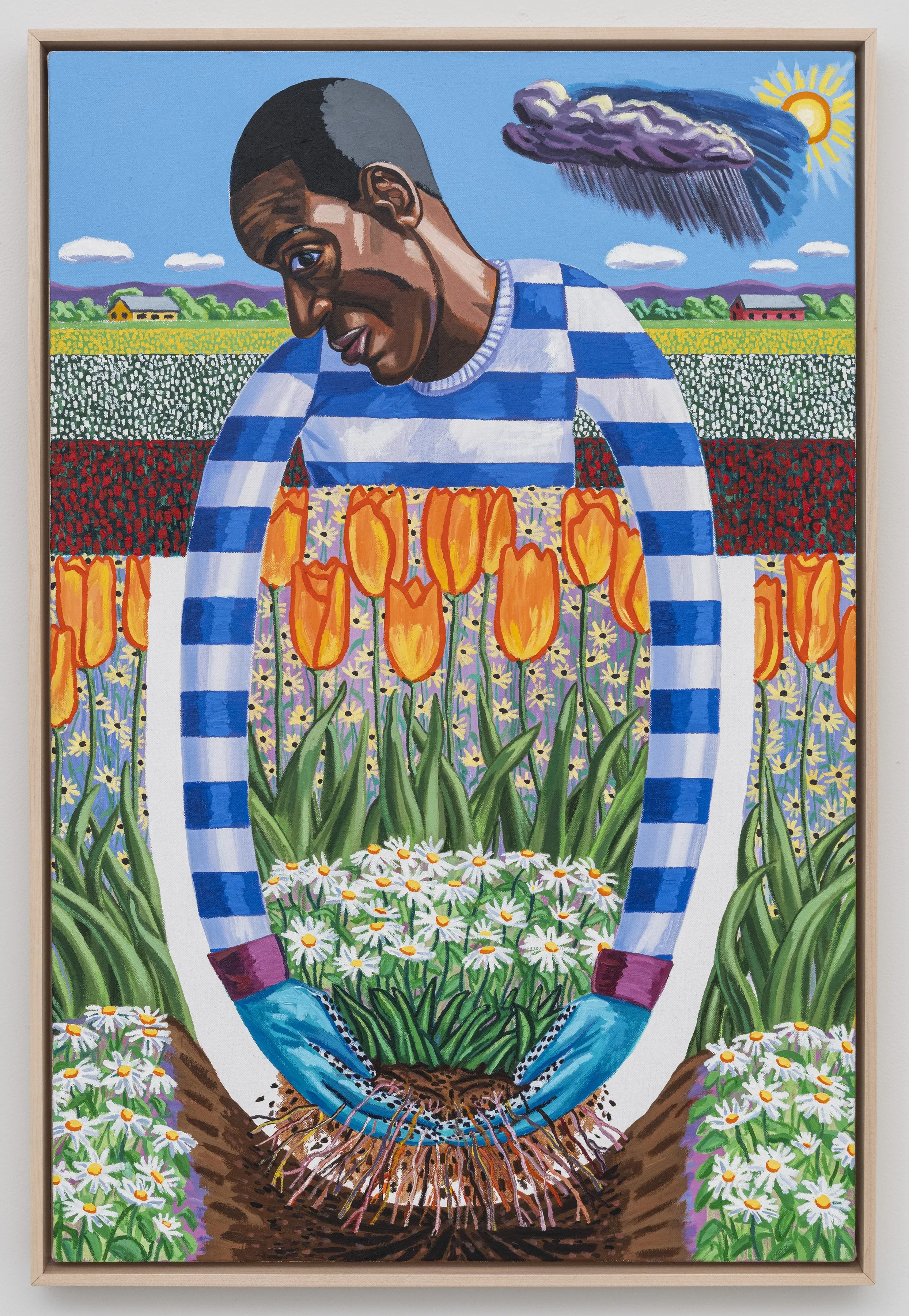

Lamar Peterson, Forecast, 2024. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Lamar Peterson, via Fredericks & Freiser, New York; Photo by Cary Whittier.

There is something studied, student-like, in the treatment of the paint in these paintings. Oil paint in Peterson’s hands is made to behave contrary to its nature: it wants to blend, but is applied without mixing; it wants to be luscious, but takes on a plasticky, acrylic-like sheen; it wants to mass in impastos, but is spread thinly across the regular weave of a store bought canvas, the peaks and valleys of which dapple the flatly painted scene. A student-like stinginess with paint, stretching too little across too large a surface, leaves halos of white gesso. Like all work by students today, the student-like slips into the digital. . The color scheme produces an impossibly saturated world, like that of a low-fi computer game; the prominent weave of the canvas grids the image like pixels; the gesso that shows though recalls the white halo of sloppy digital editing. We find ourselves in a rigid world of rules and limitations, an environment that only allows for academic prescription and preprogrammed possibilities.

The composition of Forecast is tight and awkward, as if a student rigidly applied compositional rules that were meant as guidelines. Between horizontal registers of flower fields, a black man in a striped shirt that compositionally locks him into the horizontal landscape, holds an uprooted plant, arms frozen in an 0-shape. It is here, in description, that narrative slips in, when we use dynamic verbs to describe the static painting. Beings bound in time and space that we are, we want to say, the figure pulls the flowers up by their roots. But such language is an imposition on this painting’s world. For the only type of movement allowed in its two-dimensional composition is compositional reorganization; in pulling the plants, the figure’s arms, like the Select>Move function in Photoshop, shift the middle ground they encircle along a two-dimensional plane, leaving a halo of white gesso as if revealing the blankness of Layer 0 in Photoshop. There is nothing underneath the colored surface of this world, no place for roots to take hold.

Lamar Peterson, Neighbors (Version 2), 2023. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Lamar Peterson, via Fredericks & Freiser, New York; Photo by Cary Whittier.

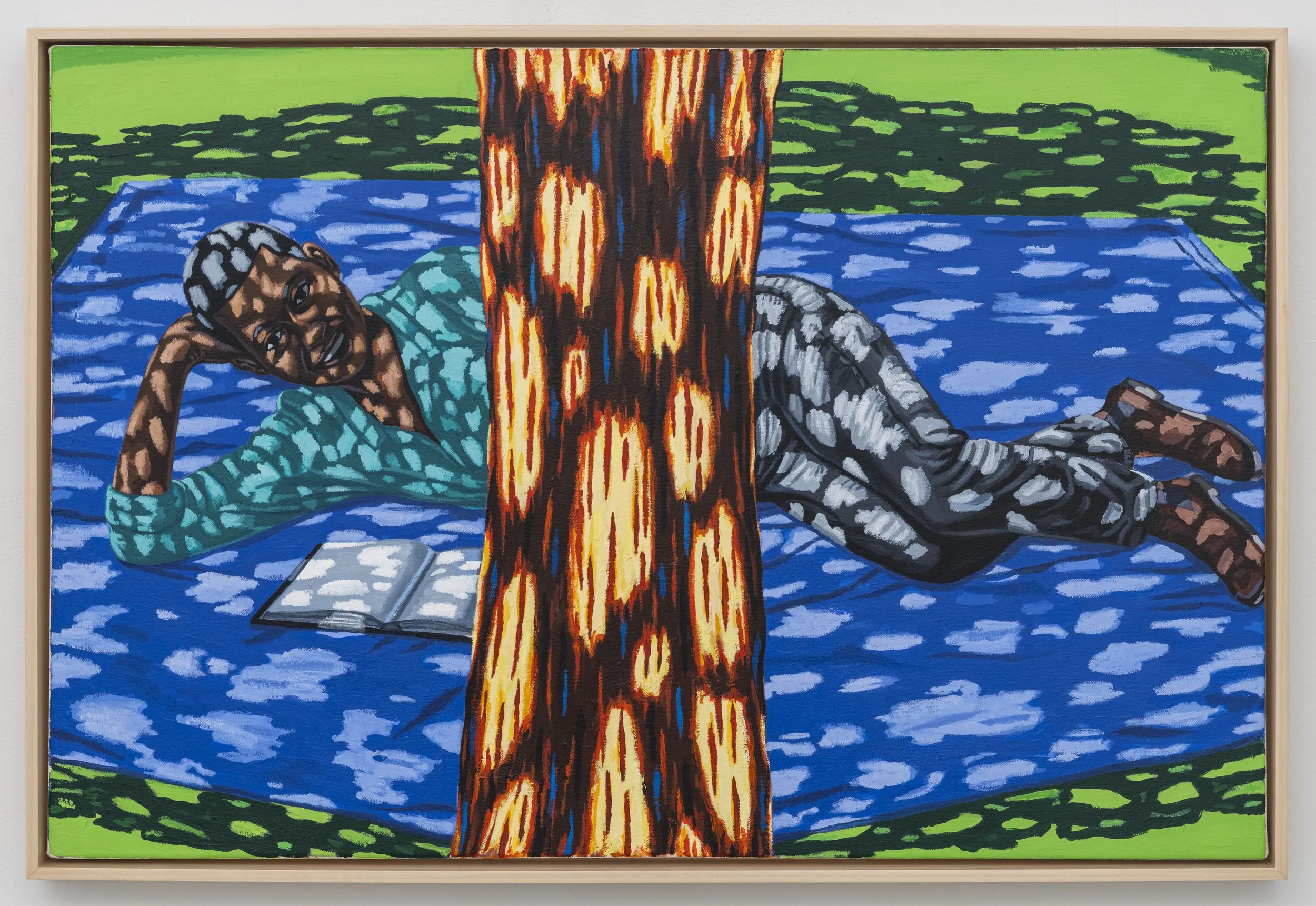

The trappings of an undergrad color theory course, manifest in the description of light effects through tints and shades, convinces in some places while in others is pushed to an uncanny extreme. In Neighbors (Version 2), the contrast between lights and darks is so exaggerated that the dappled light filtered through a tree’s leafy canopy takes on the intensity of many spotlights, light concentrated as if through a magnifying glass held by a nefarious viewer on the frozen foreground figure. In Summer Reading, the contrast between the lightest and darkest of a hue is pushed so far as to not appear as a light effect at all but part of the surface: camouflage on the clothes, vitiligo of the skin, or bleach burns on clothes and skin alike. In this world, the sun never moves from directly overhead. This world is in a constant state of utter visibility, the figures under surveillance.

The visible world of Peterson’s paintings is static, held in place by regularity, pattern, and the strict order that grows from these. There is no room for change, or its literary correlate, narrative. Pinned within registers or by spots, the figures are fit in two-dimensional space like puzzle pieces with no space to move. The black male figures are held under our gaze, for our gaze, wearing an expression that reminds us how close a smile and a grimace are. Frozen, their eyes, by virtue of their being painted, are unable to blink. The student-like adherence to rules of composition and color theory, along with the suggestion of the pre-programmed limitations of digital tools or games, pushes the regularity into conventional norms. These are worlds built for we viewers, who like a nice picture with flowers. The figures in these paintings are sacrificed to this world of (too) colorful paint organized nicely (if manically) on a surface: a world of painting where interior life is impossible. As the title of the show tells us, there only is The View From Outside.

Lamar Peterson, Summer Reading, 2023. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Lamar Peterson, via Fredericks & Freiser, New York; Photo by Cary Whittier.

For the superficial viewer, like Schwendener, Peterson's paintings will be generalized as black figuration, a narrative that "suggests" the plight of black men in mid-western, semi-rural America (though she barely goes this far, having somehow mistaken the colorful style to be cartoonishly cute, the domestic subject matter to tell a heartwarming tale of a bucolic life filled with gardening and cooking, the figures to be autobiographical depictions of Peterson rather than functions of the paintings that reach beyond the particular, empirical person to universality). In their commitment to surface, paint, and non-narrative painterly stasis, one might even say that these paintings, far from being at the vanguard of the black figuration boom, avoid the confusion of figurative work that's "about" human psychological experience to pick up a tradition of modernism, making a truly modern work that expels everything not proper to painting as an art (three-dimensional space, human psychology, interiority, time, change, narrative) to not simply illustrate but express the unfreedom of a form of life — to create a visual world that makes sensible the material constraints, both material and conventional, that limit black men’s experience today, all while staying true to painting.

Lamar Peterson, Threshold, 2024. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Lamar Peterson, via Fredericks & Freiser, New York; Photo by Cary Whittier.