The Most Constipated Man: Aesthetics in the Belly of a Worm

Is it perhaps possible to suffer precisely from overfullness?

— Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

With a corporeal belch we can answer Nietzsche in the affirmative. To be ‘cultured’ is also to dam up culture and become constipated. This Most Constipated Man, as he may be called, feels an antagonism against him by what is accumulated within him. An overripeness of culture surrounds him to such an extent that it permeates him entirely, and is uncomfortably part of him. As if buried alive in the trash heap of cultural history, the boundaries between individual and culture are permeable, fragile, and often virtually nonexistent. This creates neurotic attitudes towards art: either No more!, or I need more! One meaningful artwork would seemingly give relief, shaking the bowels loose. But it never comes. He feels no difference between culture and his waning self, because culture has simultaneously consumed him and filled him. And yet he feels unfulfilled! This cultural material is constipated in the uptight and confused musculature of living people. In turn, society and its ailments cannot pass and instead rot in the repressed bowel. In his anal retention and conservational rationality, The Most Constipated Man in part desires to retain culture, to hold onto it forever and ever. On the other hand, it must be processed. The Most Constipated Man traps the cultural world with his clenched sphincter, seeking to regulate something both overproduced and unfulfilling. And disgruntled bowels only makes things worse. He all too often resists the passage of what was naturally expected to pass. Cultural matter is changed by this turn of events, or lack thereof: it rots. It is changed by the drive to stasis. This holding changes the content that itself yearns for extinguishment and for which stasis is antithesis.

The engine of this neurotic cultural situation is a prohibition of aesthetic pleasure today. No one is supposed to find pleasure in art. An ersatz jadedness and fear are chosen over curiosity and pleasure. Jaded art institutions and culture snobs fuel the propagandizing against aesthetic pleasure, a moralistic and academic ideology that fears pleasure and says: you’re supposed to receive a boring moral from some senile fable of the present. Chaste moralists believe you’re not supposed to feel about whatever mysterious aspects of art you might feel. You aren’t supposed to be curious and let your senses roam free; you’re supposed to use your senses in the way they’re curated. Open wide, ingest the propaganda. Art in a rationalized society literally means it is rationed out like bread in a social crisis. In secret, our world is inherently aesthetic, perhaps even to a fault. Regardless of what they’re told, human beings yearn to extinguish themselves in art, to get lost in it, as opposed to grasping it. Social taboos from snobbish cultural ‘experts’ are designed to be internalized, and the epidemic extends to the general public as well, who police each other in the realm of taste. Fear of extinguishment is naturalized: people tend to hold on to their aesthetic experiences — or at least hopes — privately. Aesthetic pleasure is seized upon, fetishized, and clenched.

For The Most Constipated Man, criticism is looked to as a type of digestive aid. While contemporary culture correctly feels meaningless, it is also nothing to sneeze at, and in true self-conflicting modern subjectivity many also feel this urge to not thumb their noses at aesthetic pleasure. The Most Constipated Man implicitly understands the impulse to sneeze at things — it is an attempt at evacuation. Art itself wants to pass, it does not want to sit inside a human and rot. Likewise with the urge to vomit at the mere scent of culture. Vomiting itself has become a thing in contemporary performance art. The Roman Vomitorium lives on in the shadowy underground.

The accumulation demands an imminent reevaluation in his critical judgment — his ability to project a condition when what rots inside has passed. A good critic is no more than someone with a healthy cultural metabolism. Symbolically, it makes sense that bad critics are often portrayed as fat men. Symbolically, the recent research into the gut brain and so on is aimed at a constipated aesthetic faculty. Symbolically, it makes sense that many of our contemporary academics of aesthetics are more interested in foodie culture than art.

On the other side of vomiting — but still within the vast digestive disorder of culture — there is also the aesthetic of being consumed, as in Vore. They correctly perceive themselves as little men, in the sense of Wilhelm Reich. It’s as if people today want to symbolically enter into peristaltic processes so as to understand them. The aestheticization of metabolism, our modern heroic Jonahs! Even Jonah is eventually vomited out. Perhaps the myths of the Jonah figure — endemic to all human cultures — is a cathartic story of transformation via digestion. It’s an attempt to overcome culture by looking at it from the perspective of the cultural material itself that is dammed up in some larger historical system. But it’s telling that Jonah is vomited up and not shat out. The mammoth beast cannot digest the dissident hero. He is half-digested, if even that. If Hegel thought that Art looked like a worm chasing after an elephant when it tries to imitate Nature, we might think of our current state of art as being trapped in the belly of such a worm as it writhes through the trash heap of culture, struggling to digest it. Perhaps the meaning of all this metabolic aesthetics is the attempt to redeem Jonah — who was and still is taboo as a disobedient subject of the cosmic order — as a dissident hero with a Promethean sensibility who goes into the belly of the beast to tickle his prostate and set him free.

The present is written from the point of view of a Most Constipated Man, inside a most struggling worm, whose view to the immediate future is a relief from a present that feels overproductive — much to his discomfort. The Most Constipated Man — a type of artist working in the dark age of overproduced nihilism — tries to be productive and innovative only in theorizing how to dispose of excess culture. Not because it is revolutionary, but because it is a necessary starting point. Artists don’t need to make a virtue of the necessity of being a cultural manure factory. Artists might instead be considered in light of the cyclical concept of composting. They don’t seek a fabricated culture of stasis, but an Art of dying and life renewed. Avant-garde artists would not be slaves to lame pseudo-political trends but free to compost such trends and use the rich composted soil of history to recreate life — in turn to destroy it again — from the standpoint of being composted themselves eventually. We are undoubtedly in an era of rot. Even in the vast realm of (neo)futurist music, some of the most compelling music is that which thematizes burying the dead or going underground (e.g. Burial, Eartheater), which literally undermines the idea of any form of futurism. From a certain point of view, plunderphonics and a great deal of musique concrète can be perceived as an attempt to metabolize culture by literally processing it. Processing, like a worm, is the default aesthetic standard by which music is currently judged — music is interesting the extent to which what went in is changed. Visual artists since Duchamp have tried their damndest to simply not add to overfulness, an ascetic strategy that has proven not rigorous enough. The concern turns on the how of the matter.

What the Most Constipated Man often sees at his feet these jaded days is also cultural viscera, half-digested culture. He may be revolted by it, or he may become a cultural scatologist, intrigued by a different form of beholding in the era of evisceration. This viscera is an image of accomplishment — poor, surely, but minor and real. Even the paltriest droppings provide some relief and contain undigested kernels.

We might be inclined to recommend to the Most Constipated Man that he take a break from ingesting and producing culture literally ad nauseum, to periodically fast. Certain cultural products might also be avoided, or consumed in moderation, while others may be healthier. As fasting is symbolically tied to repentance in folklore, we wonder: what are the Most Constipated Men required to repent for? For insulting life and death by incessantly trivializing it. But, no, it’s too late! The Most Constipated Man of culture has at his old, jaded age been forced to have his cultural bowels surgically removed simply in order to survive. As if mere survival is what’s longed for. All that might be left is to ask the eviscerated, “What have you been seeking all these years with your insatiable hunger?” Or perhaps some new hunger artists will wager that the evisceration of culture means we inevitably and unconsciously descend into the realm of Dionysian dismemberment. //

Next week I will be speculating on bladders & Opera.

Mosaic of a Symposium with Asarotos Oikos in the Château de Boudry. From: Thinglink.

Martin Creed, Work No.837,2007. From: Tate.

Honoré Daumier, Ces Bons Parisiens: M. Prudhomme visitant les ateliers…, 1855. From: Artsy.

Jon Rafman, Vore, 2016. From: The Invisible Animal.

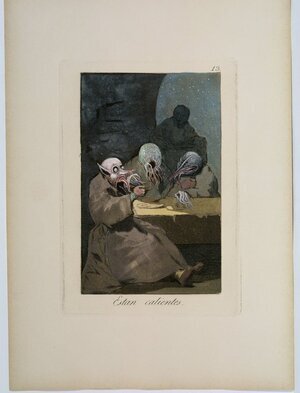

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Like a dog returns to its vomit (No. 13), 2005. From: Artspace.