On Art, Hopelessness, and Crisis, Part II

On May 2, 1808, the people of Madrid rebelled against French occupation of the city. The uprising was quickly and brutally suppressed. Hundreds of rebels were swiftly captured and executed the next day in a moment of barbarism famously memorialized in Franceco Goya’s The Third of May (1808). A man stands with arms outstretched, illuminated as if by divine light. The bodies of his brethren lie at his feet on blood-soaked ground. A dark, faceless squadron of executioners point their bayonets at his desperate form. The painting captures the very moment before his death. Its urgent gestures register profound human suffering and the sharp pang of failure. That was 212 years ago, but it feels sickly contemporary.

When I published the first part of this essay, the crisis to which I referred was COVID-19 and the resulting economic freefall currently imperiling art galleries, museums, and schools. I had planned to write more on this, but, because we are clearly living in the darkest timeline, a new crisis (or, perhaps, a new expression of the crisis) has emerged. I can hardly write an essay with the word “crisis” in the title without noting it: the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in Minneapolis and Louisville, respectively, and the protests they sparked. As I write I am watching reports of truly disturbing instances of violence inflicted by police on protesters and journalists.

Rule 34 is perhaps the best known tenet of internet lore: if it exists, there is a porn of it. There’s a similar rule in the world of art writing: if it exists, there’s an article about how art is absolutely critical to the struggle against it. Global pandemic? Art is on it. President you dislike? Art is so important in the resistance. This is not that article. In case there is any doubt, art can do nothing about this current physical illness or the longstanding social illness driving the current protests. Here I will only ask: what role, if any, does art have in crisis?

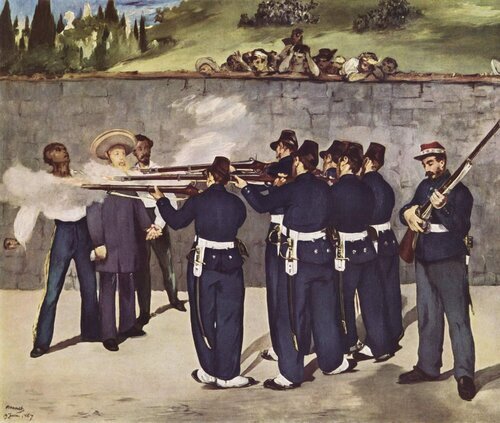

Modern art certainly did not shy away from the crises of its time. Éduard Manet’s 1869 painting The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868-69), a clear quotation of Goya’s picture, depicts the execution in 1867 of the French puppet Emperor of Mexico, Maximillian I by the triumphant Mexican Republicans. Here, the spirit is quite different. Goya’s chiaroscuro is replaced by the mundane, uniform illumination of a mid-afternoon. Maximilian’s features are blurred, almost anonymous, and has none of the righteous vitality of Goya’s victim. Rather, it is one of the executioners, in the banal act of adjusting his rifle, who is given a face. Unlike Goya’s painting this is not a tale of tragedy, but of the mundanity of victory; Manet’s sympathies lay with the Republicans. It’s all terribly quotidienne.

The tendency in the twenty-first century to make dramatic claims about art’s importance, its role in social struggles, its ability to “change the world” are symptoms of the crisis of art, in other words the crisis of bourgeois society. When the value of art is no longer given, it must be propped up by grandiose pronouncements. These pronouncements amount to a castrated scream, a desperate argument that art still matters when its vitality is most diminished. There is an excess of hollow hope. Projects like Marcel Duchamp’s — to attack art from within — have proven too effective. The impulse to “blur art and life” espoused by Allan Kaprow as early as the 1950s has blurred art to the point of unrecognizability. It has filled postwar and contemporary wings of our museums with rarified and remote objects and populated kunsthalles with baffling installations.

In the later 20th century, the postmodernists, to their credit, recognized this crisis. They understood that the category of art, like the category of history, was no longer self-evident. Rather than feel it as a loss, as the better writers of the 20th century did, they embraced its crumbling as a positive project. They (mistakenly) saw liberation in the dissolution of political, historical, and aesthetic categories. But at least they were clear-eyed about it.

We are no longer clear-eyed. My generation was educated in the canon of postmodernism, taught to revel in the promise that deconstruction will offer liberation and disillusioned to find that it has not. The postmodernists had the rocky cliffs of modernism to butt up against; we now struggle to stand in the loose sand they left behind.

We danced on the grave of modern art. We gleefully announced the end of beauty. But then what did we have left? How were we to justify our vocation after we had so thoroughly dismantled it? Pseudo-politics. Art is to be deployed as the least effective form of activism. We ask not what art is but what it can do, and must always be disappointed to discover that it in fact does very, very little.

The poverty of our age not only produces impoverished art but obscures the works that strive to overcome that impoverishment. One could be forgiven for forgetting one of the truly excellent paintings in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, Henry Taylor’s THE TIMES THEY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, after the entire exhibition was hijacked by protests against Dana Schutz’s Empty Casket, a painting based on the photograph of Emmett Till’s mutilated corpse that protestors felt Schutz, as a white woman, had no right to paint.

Taylor’s painting depicts the shooting of Philando Castille, one of too many victims of murder by police. As in the Goya and Manet, this is a picture of an execution. And as in the Goya, the executioner remains anonymous, just a few fields of color connected to what is barely more than a black rectangle, but is immediately recognizable as a pistol, pointed at the prone figure of Castille. The fact that we immediately recognize what’s going on in this scene is not just a credit to Taylor’s talent, but a sorrowful recognition of the ubiquity of this kind of image. Like Manet, Taylor is a master of the judicious use of fields and forms. Castile’s seatbelt, still buckled over his body, is rendered as a beautiful blue ribbon like an aristocratic shash. The bold, flat white of his still open eye cuts into us, challenging us with its dead stare. The flatness of the canvas creates a visceral confrontation against the viewer’s own body like a brick wall; it knocks the wind out of our chests. One may credit Taylor because he painted Philando Castile, but Taylor deserves more credit for the way he painted him.

Taylor’s painting is emotional and confrontational. Such works of quality are too often eclipsed by cold archivism or anaesthesia under the guise of “justice.” The collective Forensic Architecture’s detached installation, Triple Chaser was hailed in the 2019 Whitney Biennial for its presentation of research into the deployment of weapons manufactured by a company attached to then Whitney Board member Warren Kanders. The result was cool and without feeling; in fact, its contents were compiled by AI.

A comment from the great 20th century critic, Clement Greenberg, bears repeating here:

The great art style of any period is that which relates itself to the true insights of its time. But an age may repudiate its real insights, retreat to the insights of the past — which, though not its own, seem safer to act upon — and accept only an art that corresponds to this repudiation; in which case the age will go without great art, to which truth of feeling is essential. In a time of disasters the less radical artists, like the less radical politicians, will perform better since, being familiar with the expected consequences of what they do, they need less nerve to keep to their course. But the more radical artists, like the more radical politicians, become demoralized because they need so much more nerve than the conservatives in order to keep to a course that, guided by the real insights of the age, leads into unknown territory. [1]

It is a pity that even when art musters some quality against all odds, we are predisposed to ignore it. But the fact that quality emerges at all in such a dismal age is cause for a bit of measured optimism.

Art need not retreat from our moment to succeed as art, but it must not stoop to the remedial desire to change our moment. It is more than enough for works of art to register the human suffering the pervades our age. To register the suffering and paint nonetheless is a cry for a better world. //

Francisco Goya, The Third of May, 1814. From: wikipedia.org

Éduard Manet, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 1868-69. From: wikipedia.org

Henry Taylor, THE TIMES THEY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, 2017. From: Whitney Museum of American Art

[1] Clement Greenberg, “The Decline of Cubism,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945-1949, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).