Marco Torres

I never know how to start with “digital paintings”. I find myself in a comically similar situation to Marco when he introduced some electronic music of mine a couple months back. For my day-job, I spend hours scrolling through the endless imagery of sites like DeviantArt, Flickr, Tumblr, 4chan, etc. I see so many Photoshop doodles — depicting beastiality or decapitation fantasies, or whatever else — on a daily basis that, at my worst, I am numb to the artistic impulse which lies beyond the sterile “ultra-flat” artificiality of digital colors, geometric paint brushes, color shading effects, etc. When I see a digital picture it is difficult to see beyond it, to feel it. In this pseudo-presence, the bewitched experience of a work of art lies beyond an impasse.

I was brainstorming for a show proposal the other day which would feature the works of a prominent “Post-Internet” video artist alongside the drawings of Joseph Beuys. One point of emphasis in my scribbles was that image-making culture (particularly the mass proliferation of imagery onto digital platforms which often use digital tools in creation) is today an overripe fulfillment of Beuys’s fantasy of a totalized and totalizing art-making social organism. And that on the other end of this development, many digital artists have found their task to be crystalizing their online encounters into new condensed images. These condensed images aren’t so much of a composite or index as they are a substantiation or a distillation of digital images.

I’ve had similar thoughts in conversation with Marco before. I don’t want to botch the nuanced and brilliant words he probably uttered at the time (which admittedly have almost totally faded from my memory). But his attitude, which I shared, was along these lines: that today there is a strange appearance of the death of art; it’s utterly obsolete and in ruins. Yet at the same time, there is more art being made, viewed, read, and talked about than ever before in human history. It’s not just meme-making, the whole culture industry seems to have been turned inside out, having gone from thriving on broadcasting to a passive audience, to thriving on an active audience producing content for itself. Examples are well-known: Instagram curators and influencers, DJs everywhere you look, enough podcasts to go to the Moon and back, online-grown celebrity tattoo and make-up artists, an endless supply of homemade furnishings or nick-nacks on Etsy, foodie photography, Twitter poetry, TikTok music videos, dramatic shorts on IG reels, DeviantArtists, homemade comics and zines, homemade films and posters, skateboard videos which more and more take on the city as a surrealist muse… I don’t need to go on, it is familiar to all of us.

Today, everyone is an artist. Beuys’s famous proclamation has been taken more literally than he perhaps intended or foresaw. And this didn’t happen overnight, but has been growing and growing until we needed systems like Etsy and Instagram — the Internet — to manage it all. On the one hand it seems that never before in the history of humankind has artmaking enjoyed so much attention and fervor. On the other, never before have images been so forgettable. Is this the victory of art or its defeat?

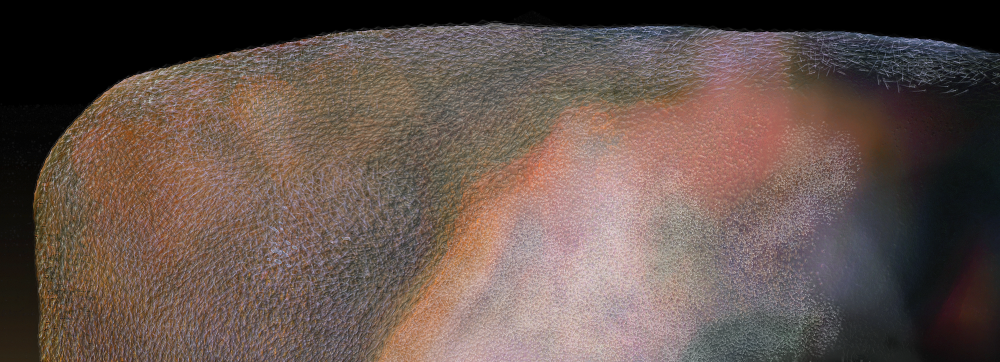

But this is all beside the point. It is merely to set the stage; it’s part of the way I imagine Marco Torres, a historian of 20th century modern art by day, thinks about his own drawings at night. The two works shown in this portfolio which most pique my attention are Detective Sergio, Miami PD and Sewer Strider. Detective Sergio is pressed up against the pictureplane like evidence on a scanner, only a portion of his warped head visible. He looks more like a victim than he does a detective, his scaly skin bruised and molten, his head lumpy and deformed like a battered newborn; perhaps he is a dumpster-baby all grown up, enlisted in the service of Miami’s special bodies of armed men. Zooming in reveals a surface that looks more like a crumbling cement wall stained with decades of graffiti. His delicate eye is rendered like a Blue Marble smoothed in a matte finish and surrounded by scores in the pavement for eyelashes. The familiar effect of focal depth from photography, of contrast between objects in focus and in blur, is painted on like high-gloss make-up. An inspection of the ear reveals a wet cave, glistening and inviting. The mustache falls from the nostrils like feathers from the sky, and lava churns under the surface of the skin around it. Many of the shapes of the features are accented with a bright sketch line, reinforcing the forms described by undulating color. Like many of Torres’ works — like many figurative digital drawings in general, for that matter — the background seems like an afterthought, just some color to fill the empty space and set the mood. This is probably why they appear to me more like sketches than paintings. (One honorable exception to the sharp foreground/background habit is Woman’s Head 2 in which the planes are smoothed into one another; any clear horizon between foreground and background effaced.)

The Sewer Strider is Sergio’s cousin. If Sergio got tossed in the dumpster, the Strider was flushed. Ironically, the shadowy figure’s knees tilt inwards, holding back an excretory impulse. He mops along with caked-on sparkles and a red-glow halo, perhaps hunting rats or other sewer delicacies. With each step, a small cloud of glitter blooms around him. Perhaps this explains the halo. He looks cuddleable. Much more luscious than his beaten-down cousin. Life in the sewers isn’t that bad. Not as bad as life on the street. The mazes of a sewer system are just as easily a site for a fairytale as the magical forest. Our intangible prince charming roams the corridors like a phantom, glossed with the haze of a rainbow. The texture and shading here look very different from those in Detective Sergio. But they do imply a similarity of technique. Both seem to be made of layers of texture and color patches that are later smoothed and highlighted or shaded with transparent blurred-strokes. Other than a few misplaced smudges which only detract from the soft-shaped glob figure, the illusionistic shading and smearing sharply differentiate the figure from the flat background of a stone block wall with two arches. Again, as with Sergio, all the action is delimited sharply into foreground and background.

Other standout drawings from Torres are the stoic and tantalizing Androgynous Head, and Detective Sergio’s partner-in-crime, the vaporwave-influenced Dectective Dario, Miami PD, and the impressionistic Ghoul’s Head. All of these listed above have a cool and tempered atmosphere. Their colors and forms, though far from static or cold, are controlled and considered. By contrast, works like Man’s Head, Orc’s Head, or Cyclops Head, are farther down the “chaotic” spectrum. Their colors and forms disintegrate under a mysterious chemical influence. Their edges and surfaces flash out like prisms and disappear into the background.

The images capture the moment when, in the midst of a stroll down a noisy Internet boulevard, the artist sees himself reflected in the computer glass. The images contain the distortions in vision which emanate from prolonged online exploration. The artificial and sharp blues and the differentiated tones of LCDs are recaptured swirling around portraits of imaginary characters, each of which could also be a portrait of the artist himself. The artist is reflected and refracted through the screen, just as he is through archetypal personas or avatars.

—Grant Tyler

(from top to bottom, left to right)

Sewer Strider, 12 x 15 in, 2020.

Man’s Head, 12 x 12 in, 2021.

Man’s Head, Pencil on paper, 9 x 11 in, 2021.

Woman’s Head, 12 x 12 in, 2021

Ghoul’s Head, 12 x 12 in, 2019.

Orc’s Head, 12 x 12 in, 2021.

Androgynous Head, 12 x 12 in, 2021.

Cyclops’ Head, 12 x 12 in, 2020.

Detective Sergio, Miami P.D., 12 x 12 in, 2021.

Detective Dario, Miami P.D., 12 x 12 in, 2020.

Athlete’s Head, 12 x 12 in, 2019.

Woman’s Head, 12 x 12 in, 2021.

Marco Torres was born in San Antonio, Texas and grew up in Monterrey, Mexico. In the early 2000s, he moved to Chicago to attend art school, where he stopped making art. Many years later, while pursuing an academic career as a historian, Marco got himself a Wacom tablet and started painting pictures on Photoshop and posting them on Instagram. He lives in the twenty-first century, where he wishes he could somehow, someday teach himself fifteenth century Flemish portrait painting technique.

You can see more of Marco’s work on his Instagram.