Justin Ortiz

When the poets repair to the forest of language it is with the express purpose of getting lost; far gone, in bewilderment, they seek crossroads of meaning, unexpected echoes, strange encounters; they fear neither detours, surprises, nor darkness. But the huntsman who ventures into this forest in hot pursuit of the “truth,” who sticks to a single continuous path, from which he cannot deviate for a moment on pain of losing the scent or imperiling the progress he has already made, runs the risk of capturing nothing but his shadow. Sometimes the shadow is enormous, but a shadow it remains.

— Paul Valéry

Despite what he may wish, Justin Ortiz works within a mode of painting that has become prevalent in the past few years. This is a kind of painting marked by an attraction to fantasy, Symbolism, surrealism, and the mythic. Many of the works of this loose genre feature cartoonish figures, earthy and organic tones, and dramatic light, sometimes setting off the organic shades against starkly artificial colors. They take flight from the paranoia and stresses of the world’s problems into the mist of the imagination, into stories and legends, dreams or religions, which form the basis of their inspiration. Julien Nguyen is a high exemplar of this mode. Kira Scerbin, the cover artist of Caesura’s first issue, is another example. Ortiz will have to work through his ambivalence about being counted among this trend. That such a narrow and stylized vision for new art spontaneously catalyzed a cohort of painters, sculptors, video artists, fashion designers, musicians, and animators in the United States, Europe, and Asia around the time that post-internet art petered out is not accidental. Its popularity and traction is a reaction to the “inflection point” of 2016. No matter Ortiz’s ambivalence, it cannot be avoided. Rather it must be taken up directly: head-on and consciously.

I can’t help but suspect that, with certain works, Ortiz sacrifices aesthetic potential in an attempt to engage the base conceptual discourse of Contemporary art: in these cases, he captures only his own shadow. This was particularly the case with a brief series of works — the “aliens,” as he once referred to them — in which cartoonish, colorful creatures stare out at the viewer from a deep blackness, surrounded only by the artist’s tools: a right angle, stretcher bars, a power drill. While the comportment of these works is rather infantilizing — and they are, to be frank, not very beautiful — they pose a valuable aesthetic question point-blank: is the material of the art the stretcher bars or the blackness that surrounds them? Perhaps the beauty is not in the paintings, but is among the beholders, hence the outward glances of the aliens. Whatever the case may be, these pictures give off the odorless fumes of contemporary art: they suffer from an overwrought logos and an absence of pathos.

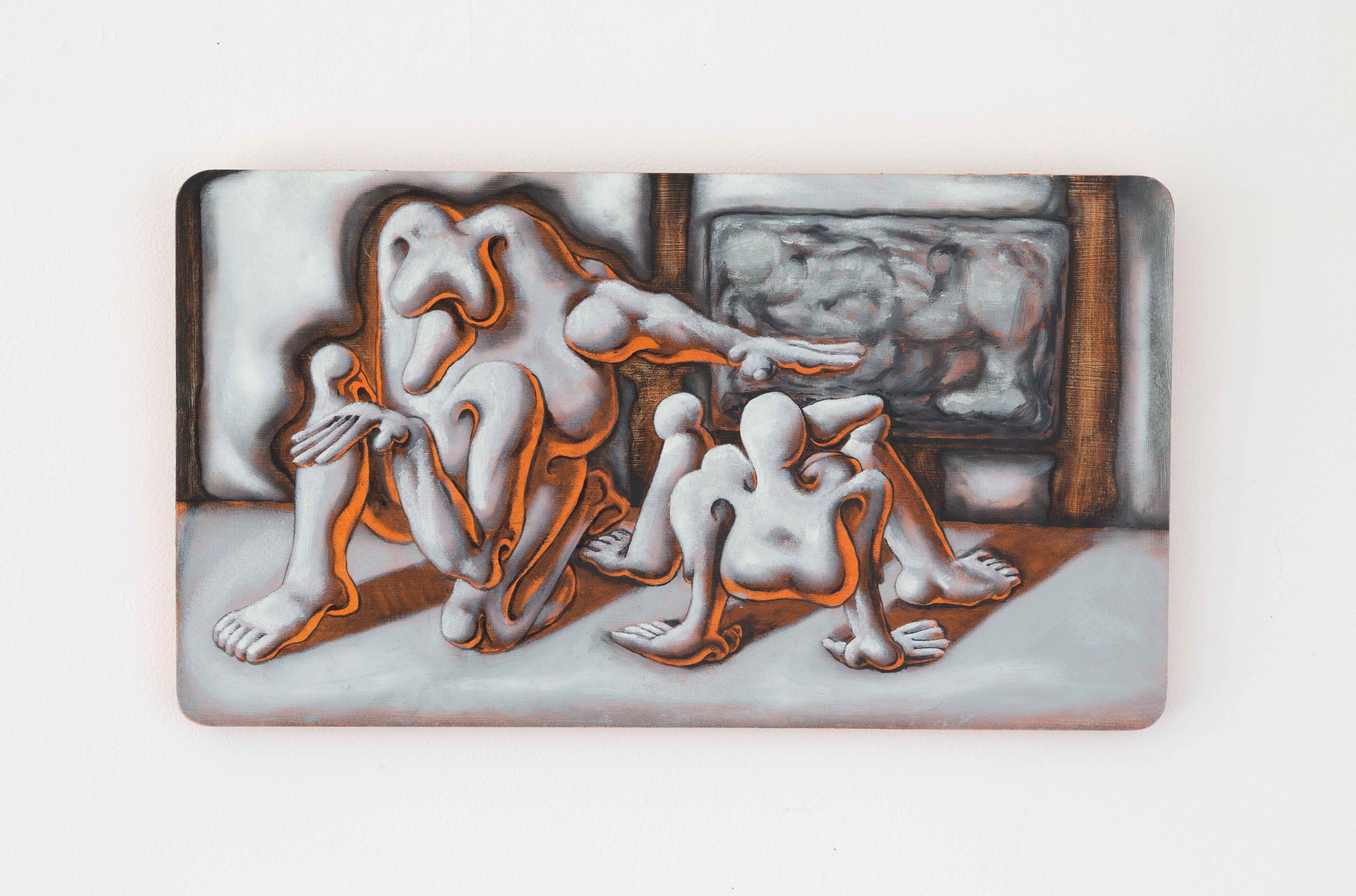

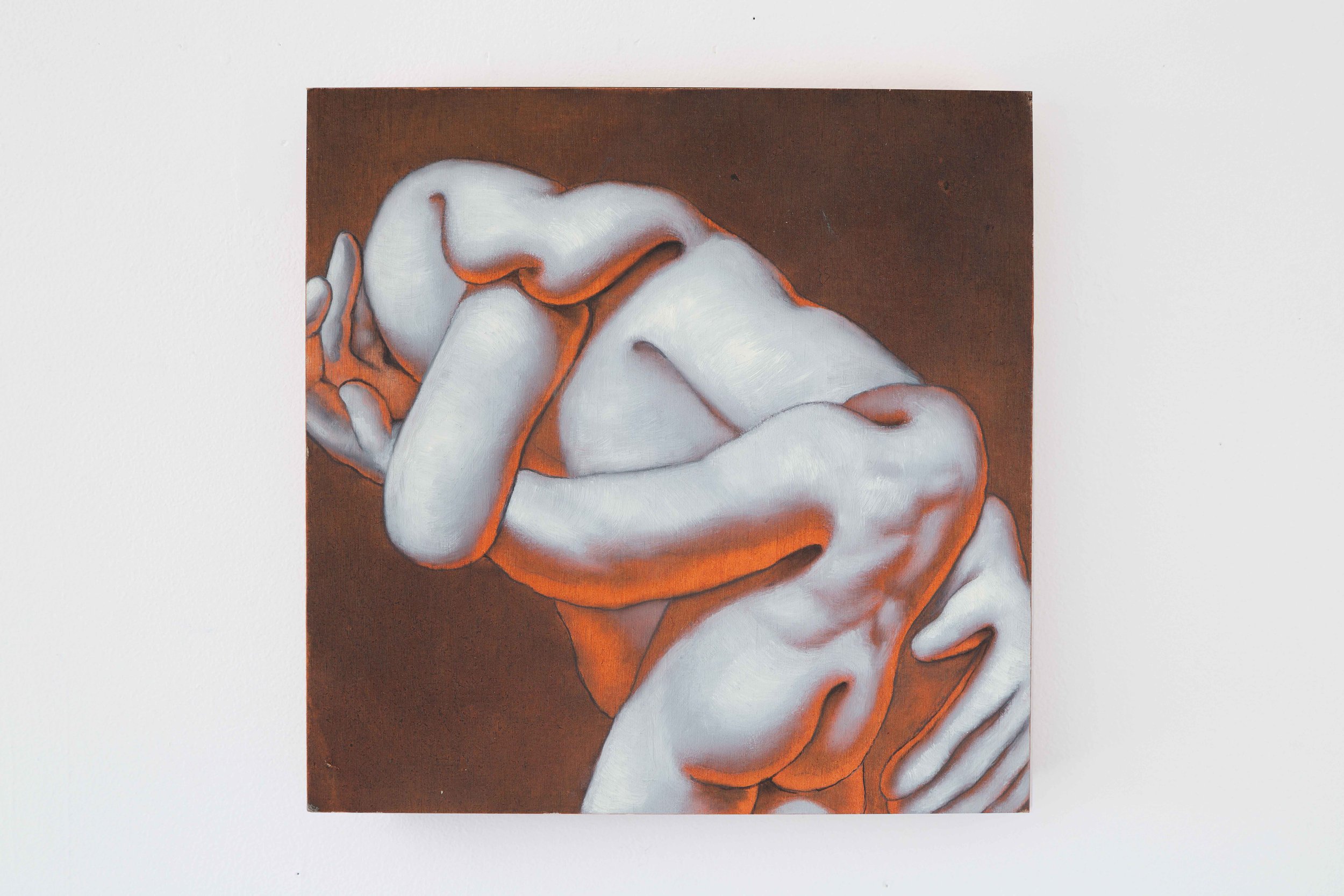

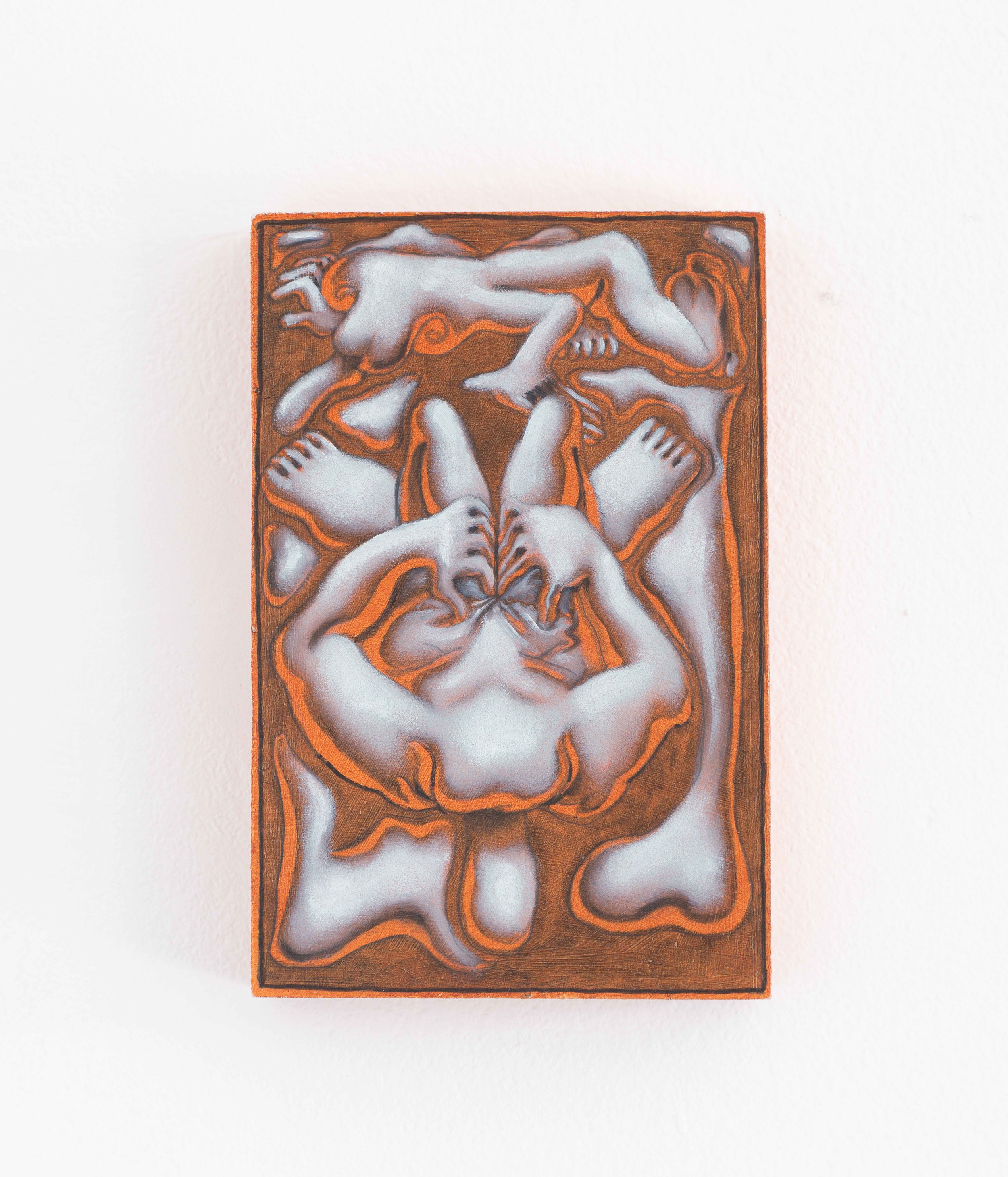

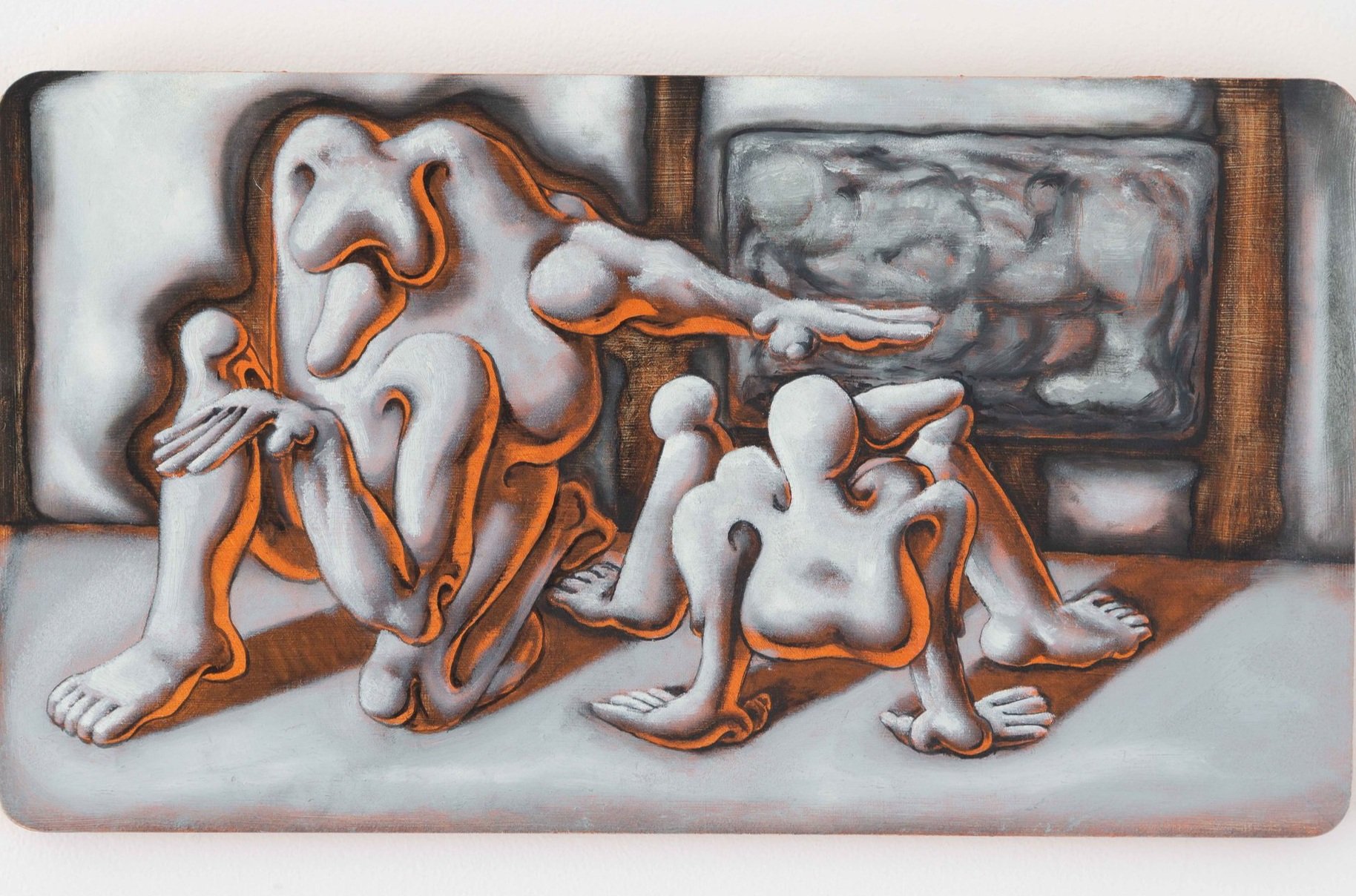

The Pleasure Guttus pictures are ripe for stirring potent reactions, and to some extent they embody the classic erotic dynamic of attraction and repulsion, but still they are limited. They are masks of what they ought to be. The charge of the Pleasure Guttus works comes from their veiled eroticism. The curves of the forms and the shading of the light seem electrified by something not pictured. But in certain works, like Snotmongers, this veil reveals the distinct contours of that which it conceals, and is rendered superfluous. This is one element which hampers the work’s latent aesthetic power. Otherwise (and Ortiz’s newest works seem to address this), they appear to be études for something more ambitious, more dynamic, and more powerful. What any artist ought to strive for is the ability to leverage play with reflection, to capture spontaneous inspiration through what is a laborious and drawn-out process. Ortiz speaks of wanting his pictures to “click,” which, although a very common way of putting it, begs to be explained. In my mind, it must be the settling of play into repose. In the Pleasure Guttus works he was able to achieve this. But it is only one rung on a long ladder towards discovering his works’ potential. Snotmongers is among Ortiz’s better works, but it still asks to become something more, a negative index of its own shortcomings.

Moongazers, remarkable in part for Ortiz’s fruitful venture into a new material and technique, is an evasive picture. It takes some orientation before one feels fully prepared to enter into it. But this preparation is rewarded. It is a wood carving of two figures, backs turned to us, the right one squatting with an arm around the left one, who returns a caressing arm, and with the other arm shields its eyes from the light of a mysterious crescent moon in the distance. Opaque to the viewer, obscured by the position of the figures in the scene, there must be a splendorous moonlit vista filling their gaze. The dominant figure on the right, holding and held by his lover (who is really nothing more than a ghost) is possessed with profane conviction, pointing to the sky. (Like Leonardo’s St. John the Baptist or Raphael’s Plato, our moongazer marks the presence of illumination.) He embodies the fullness of love and its loneliness, and is himself a conduit of beauty. The rocks and wind are animated by and shot through with passion. The whole scene blooms from the power of the moongazer, and in turn the viewer sees themselves in him.

A certain painting — which Justin has confessed to me to have little interest in pursuing further — contains, I believe, the seeds of an entirely new body of works. It is older than any other works mentioned here, and I saw it only briefly, when Justin brought out the unstretched canvas and unrolled it for me in his studio. It is a from-life portrait of a young man, boyish, shirtless, and stoic, like an older man of experience and knowledge, but with the soft and glowing body of an innocent child. He is contained under two larger fleshy forms — legs — which, with their scale and position in the picture, dominate the seated young man. But he stares past them with an air of cool detachment, verging on boredom, lost totally in his own thoughts. Ortiz’s talent as a painter is on full display here. The light contours the young man’s skin like a blanket. The shape of the chest is as androgynous and uncanny as any of Ortiz’s abstract figures in the Pleasure Guttus works and is enlivened by a character with a wealth of personality. His hair appears to have been painted all at once and could melt into liquid at any moment. But above all, his countenance, mysterious and captivating, intensifies what is lurking behind all of Ortiz’s works: an unspeakable affective persuasion, the mystery of beauty, and the blackness of its well. It invites us, the viewer, to remove ourselves to those complex worlds within, “with the express purpose of getting lost.”

(from top to bottom)

Snotmongers, 2021. Oil on panel.

Administration Game, 2021. Oil on panel.

Overlappers, 2021. Oil on panel.

Overhang, 2021. Oil on plywood.

Touch Diagram, 2021. Oil on panel.

Figurine, 2021. Oil paintings.

Interior, 2021. Oil on panel.

Moongazers, 2021. Cherry relief.

Hill Jamie, 2018. Oil on canvas.

Nose Pull, 2021. Oil on plywood.

All rights are reserved.

You can see more of Ortiz’s work on his website and Instagram.

Pleasure Guttus was Ortiz’s solo exhibition at Five Car Garage in Santa Monica, California in 2021.