Trying to Understand untitled-game

Je me mire et me vois ange ! et je meurs, et j'aime

- Que la vitre soit l'art, soit la mysticité

A renaître, portant mon rêve en diadème,

Au ciel antérieur où fleurit la Beauté!

Mais, hélas ! Ici-bas est maître : sa hantise

Vient m'écoeurer parfois jusqu'en cet abri sûr,

Et le vomissement impur de la Bêtise

Me force à me boucher le nez devant l'azur.

Est-il moyen, ô Moi qui connais l'amertume,

D'enfoncer le cristal par le monstre insulté

Et de m'enfuir, avec mes deux ailes sans plume

- Au risque de tomber pendant l'éternité ?

“I see myself — an angel! — and I die;

The window may be art or mysticism, yet

I long for rebirth in the former sky

Where Beauty blooms my dream being my coronet!

But, alas, our low World is suzerain!

Even in this retreat it can be too

Loathsome — till the foul vomit of the Inane

Drive me to stop my nose before the blue.

O Self familiar with these bitter things,

Can the glass outraged by that monster be

Shattered? Can I flee with my featherless wings —

And risk falling through all eternity?”

— Stéphane Mallarmé, “Les Fenêtres”

The oeuvre of the art collective JODI (1994 - present), comprised of Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans, has several elements in common with tactical media, hacktivism, and modern abstraction. Traces of the categories of “absurdity,” of “erasure,” of “modification,” of “subversion” or their opposites permeate it as natural landscapes permeate the desktops of countless home computers: occasionally, the windows break open the veneer and reveal the pixelated starless ether of something like computer programming. But JODI’s form — conceived by some critics as a didactic “glitch effect” — actually absorbs functionlessness and meaninglessness into its content and must be worked through upon its reception by the individual viewer. Conformity is rejected along with the comprehension of the work’s meaning. This flies in the face of the accepted interpretation of JODI’s work in which the recalcitrant attitude of the hacking and glitch ethics clings to the semblance of spontaneity in the artifact of the technical error. The hack and the glitch are petrified as an effect ostensibly representative of an ethic or “way of being” that authentically resists the social by virtue of its apparent capricious irrationality. Subsequently, this ethical interpretation stops at the technical artifact representative of error: just another moth taped to the error report on the quickly accumulating junk heap. This tends to engender a melancholic complacency with the unredeemed potential of the form of production from which the error sprung, thereby missing the opportunity for self-reflection on the tragic character of modern technology. As Walter Benjamin had put it in “One-Way Street,” the courtship of the cosmos by man was enacted in the spirit of technology, but because of the compulsion to use it to reproduce the same social relations in ever new forms, technology appears to have betrayed man and “turned the bridal bed into a bloodbath.” The celebration of the effect of technical error blunts reflection on this historical juncture in which technological production has outgrown the social form from which it burst forth. Consequently, form may only appear as a superfluous and obsolete kind of technique, an effect, representing a past state of existence, or a past state of being. Or worse, it may actually appear to be the case that the medium is the message. In JODI’s work, this vertigo is not merely thematized through the aesthetics of technical errors, but further thought on the part of the viewer becomes as much a means of producing a meaning for the work as does its form. This is because it is not immediately rendered understandable like a message, but rather tasks the viewer with overcoming his own superfluity, his own meaninglessness. JODI’s most significant gaming work, untitled-game (1996-2001), could be experienced along this continuum.

Untitled-game, like most of JODI’s work, has been understood in terms of a formalist position often held in response to 20th century abstract painting: viz., that the representation of objects as they naturally appear abases the purity and potential of the medium itself. For instance, according to Alfred H. Barr, who articulated the abstract artist’s rejection of representation, “Resemblance to natural objects, while it does not necessarily destroy these aesthetic values [of color, line, light and shade] may easily adulterate their purity. Therefore, since resemblance to nature is at best superfluous and at worst distracting, it might as well be eliminated.” Barr understood this “dialectic of abstraction” as a tension between the impoverishment of the painting from the elimination of the connotations of its subject matter, on the one hand, and the emancipation of painting to realize its peculiar forms, on the other. This subtractive element is recognized by Dirk Paesmans himself, who has characterized untitled-game as “an erased version of Quake.” Much of the existing literature on the piece affirms this view, [1] responding to the visual experience of untitled-game: all that remains from its source material are stark black and white moiré patterns, basic 3-D geometries, monochromatic screens, traces of computer code, and the original audio.

This abstraction of natural figures in Quake results in a certain aesthetic ugliness: one which suffers from an overwrought attention to functionlessness. In untitled-game the technique of abstract art becomes an effect: mere evidence that the dialectic of abstraction described by Barr above has occurred. This is reminiscent of the superfluity of aesthetic technique in the hacking ethic in general: it purports that ends can be achieved through the tweaking and modification of already existing technical systems. In untitled-game the terminus ad quem of this ethic is lost since it becomes apparent it was only ever ornamental: whether as a ritualized political statement or as the evidence of a fact that abstraction has occurred. This is not simply a matter of judgement on the part of JODI, but appears to be a contradiction internal to abstract art itself. [2] The impulse to reduce the artwork to a matter of technical innovation is in direct tension with the impulse to dissolve the barrier between art — where technique still appears to have autonomy — and life — where we are haunted by the unfulfilled possibilities of technology. It is this contradiction that proffers a break out from the ceaseless portrayal of particular states of being so that the artwork may evince an experience that no significant system of language — or technology — could carry on its own.

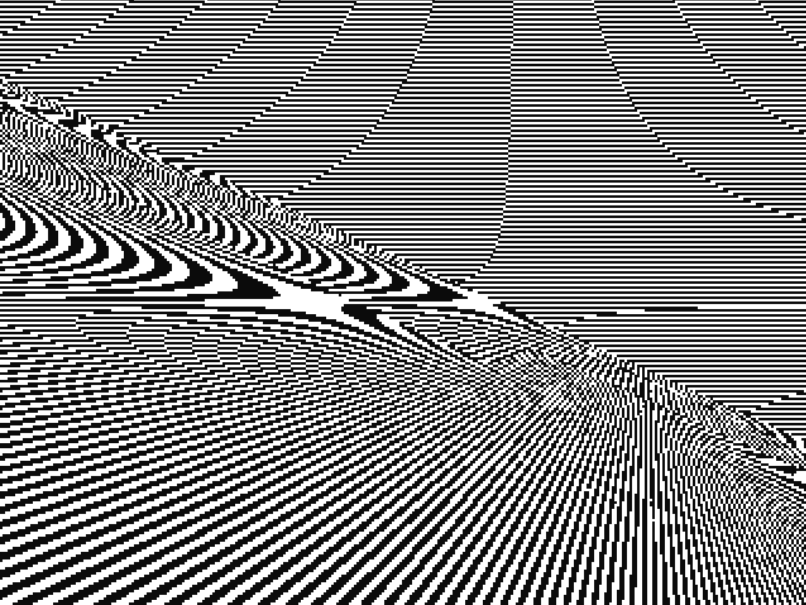

JODI. untitled-game: CTRL-F6. 1996-2001. Rhizome Conservation Fellowship

JODI. untitled-game: CTRL-F6. 1996-2001. Rhizome Conservation Fellowship.

Two critics who have attempted to comprehend untitled-game are Alex Galloway and Rosa Menkman. Interestingly, although both believe that untitled-game represents the high-point of game aesthetics, Galloway believes untitled-game to be offensively apolitical while Rosa Menkman believes it to be inspiringly political. What each shares in common with the other is their assumption that the functionlessness of untitled-game’s form is in fact an accomplished challenge to existing social reality, which betrays a post-political sensibility of the time of the game’s genesis: namely a hacking ethic.

Galloway recognizes a “formal dialectic” in untitled-game: at the same time that untitled-game rejects the figurative and natural elements of Quake’s gameplay, it “propels the game into fits of abstract modernism.” [3] Borrowing Peter Wollen’s seven theses on counter-cinema as a model to develop a grammar of the erasure of the representational in computer games, Galloway argues that Jodi opposes the formal norms of game modifications. They bring the apparatus into the foreground with real-time streams of code, they reject narrative continuity and typical gaming physics, they eschew the representational, albeit cartoonish, 3D models of monsters typical of Quake, and instead use glitches in the graphics engine of the game. The game’s controls are disconnected from the physical game space such that the user cannot trust his ability to control the game. In this way untitled-game rejects gamic interactivity for an artistic non-correspondence. As Anne Marie-Scheiner put it in a message to Nettime Listserv “I am no longer player god in control.” This is the only reservation Galloway has with regard to untitled-game. He believes it lacks a radical orientation towards gamic actions because the player is forced to abdicate his control and instead JODI apparently prioritizes better aesthetic abstractions, and is thus apolitical. Such a contention is reminiscent of the Socialist realist attack on modern art as bourgeois decadence.

JODI. untitled-game: CTRL-F6. 1996-2001. Rhizome Conservation Fellowship

Menkman, on the other hand, attempts to develop a critical framework wherein social life is commensurable with the technical by defining glitch as an activity over time: a critical momentum that functions dialectically in a destructive generativity, similar to Barr’s dialectic of abstraction. [4] Jodi’s untitled-game shares the privilege of being Menkman’s primary example of this “intentional faux-pas” in violation of accepted social norms and rules. Menkman argues that by subverting the formal characteristics of the video game, untitled-game is in opposition to the ideological values inherent in the videogame medium: namely, self-improvement, competition and victory. She puts faith behind the platitude that by repurposing a medium for another kind of play, untitled-game “rebels against techno-social determinism.” Menkman concludes it is only through new forms of play that the user can see that glitches do not simply erase the old game, but in fact modify its existing structures, and thereby add new meanings.

Galloway and Menkman’s views are two sides of the same dialectic of abstraction. They affirm that in untitled-game, abstraction becomes an effect achieved by computer emulation, while the aesthetics “natural” to computers are made artistic by revealing those places where they are reticent, functionless. Galloway affirms the first aspect of this dynamic, venerating JODI’s aesthetic achievements while Menkman affirms the second aspect of this dynamic, commending JODI’s glitch effects as an actual challenge to an ideology internal to the videogame medium, thereby ostensibly bridging the gap between life and art. In both analyses the artwork is understood as a technical effect evoking a particular state of being and acts as mere evidence that a particular kind of social opposition or innovation has occurred.

Their perspective compliments post-political attitudes of the time of untitled-game’s genesis and distribution. This can be exemplified by David Garcia’s and Geert Lovink’s ABC of Tactical Media and Mackenzie Wark’s Hacker Manifesto. Garcia and Lovink in ABC of Tactical Media asserted that by exploiting consumer electronics and expanded forms of distribution (i.e. public access cable and the internet) groups and individuals who “feel aggrieved by or excluded from the wider culture” could create new “practices of everyday life.” Lovink later wrote with Florian Schneider that these political practices, which they characterized as a reaction to the fall of the Berlin wall, in actuality did not lead to a political movement but rather, opportunistically, aimed to form “new coalitions” within the media environment as it already existed while the development of new systems were “still up for negotiation.” [5] Mackenzie Wark in Hacker Manifesto similarly argues for a political hacking practice that does not aim to change the status quo, but rather “seeks to permeate existing states with a new state of existence, spreading the seeds of an alternative practice of everyday life.” Confronted by the loss of the semblance of 1917, the hacking ethic revolts against the project of history by finding complacency in new technological forms of expression corresponding to states of being. The appeal of this slacktivism is the mocking of a reconciliation with technology as it already exists through a rebellion against it, rather than a pointing towards its possible self-overcoming on its own basis. The real helplessness of accommodation masked by the passionate propaganda of self-assertion is turned into a virtue.

JODI. untitled-game: CTRL-F6. 1996-2001. Rhizome Conservation Fellowship

Similarly, Galloway’s and Menkman’s critiques of untitled-game do not grasp the moment when its functionlessness becomes that which it is not. The loss of meaning and lack of function in the overwrought rationality expressed in works of abstraction, such as untitled-game, expresses a kind of unfulfilled potential, or unfreedom. Yet, in doing so it seeks to make meaning of suffering in unfreedom and thereby aspires towards freedom. Where it aims to be, it aims to be nothing. However, to this end it is entirely unsuccessful since the viewer is tasked with making meaning of his own nothingness. What is left over from untitled-game’s inability to be nothing is the experience of the impossibility of overcoming mere being, that is, the impossibility of history. The hacking ethic “made do” with the end of history. In untitled-game, history devours the hacking ethic.

Before the gameplay even begins, the player of untitled-game is not given much with which he could make sense or meaning of his experience. It is not only Quake that JODI has attempted to erase but also the iconographic figures typical of Apple’s graphical user interface. The main file to access untitled-game is represented by a white square icon bordered by a thin black line with the caption UNTITLED GAME. When clicked, a directory opens with fourteen subdirectories all of which are not immediately visible. These subdirectories have been given a white icon, and their filename is titled with a string of white blank spaces (Unicode Character 'SPACE' (U+0020); also ASCII 32). Consequently, in either LIST or ICON view the files appear absent, and the directory appears vacant. It is not until one clicks and drags the mouse over the white area of the Finder window that the files are then highlighted so that they may be opened. This constitutes a confusion of background and foreground, where the white background which represents the root directory UNTITLED GAME is not anon distinguishable from the white figures in the foreground which represent the fourteen subdirectories containing the executable files. Just as Malevich had overcome the typical background of the blue sky by ripping through “the blue lampshade of the constraints of color” [6] and swam into the abyss of the white, JODI breaks down the distinctions endemic to interface navigation by making the interface appear similarly transparent in whiteness. Nature, the blue sky, or the user’s naturalized workflow — his digital Erlebnis — reveals its facade of having yet to be mastered.

The first subdirectory in the list contains the mod titled ARENA. When clicked, a black and white dithered Quake menu is launched, into full screen, from which the user may select to begin a NEW GAME as a SINGLE PLAYER. Both selections are followed by the sound of a confirming gunshot. A black screen with white text appears alongside a bitcrushed thud, as though something had fallen, and rapidly draws, like a curtain, upwards toward the top of the screen. It reads:

SOUND SAMPLING RATE: 11025

CD AUDIO INITIALIZED

INPUT SPROCKETS INITIALIZED.

EXECING QUAKE.RC

EXECING CONFIG.CFG

EXECING AUTOEXEC.CFG

3 DEMO(S) IN LOOP

VERSION 1.08 SERVER [64638 CRC]

Revealed in the wake of this curtain is a pure white square, which had been foreshadowed by the aforementioned iconography, save for a black bar at the bottom of the screen featuring three sets of digits: 0 000 250. There are two seconds of silence, followed by an onslaught of howls, screams, gunshots and barking. The space-bar triggers a violent grunt. The return key and left-click result in an explosion. The necrophilic wall of sound becomes a license to kill in a fatuous rejection of the Great Commandment.

JODI. untitled-game: CTRL-F6. 1996-2001. Rhizome Conservation Fellowship

Even the player’s movement is abstracted in terms of the three digits at the bottom of the screen. His progress is commended by bars of black with white text which briefly flash across the screen commending the player for completing such arbitrary tasks as finding nails and secret areas and mourning the player's many deaths. The personal history of the character becomes the fact of many deaths. Conscious of the inability to be, he then decides to be nothing. We are reminded of the promise of technical innovation, freedom, but only through its negative image in arbitrary, superfluity. This evinces the commonplace confusion of technological progress for human progress.

The player of untitled-game must enact a Macbethian logic: the spell of technology becomes indistinguishable from history and appears to creep incrementally, in and of itself, towards either the player’s pyrrhic victories or his certain in-game death. The player of Quake is named “player,” while the player of untitled-game is named “——,” set to signify nothing. In this sense, even the player is rendered superfluous. The only control available to the player is to try another of the thirteen possible sections of untitled-game. However, regardless of the section, this dynamic of the gameplay, which frustrates the user ad nauseam, does not cease. The sections titled CTRL-9, CTRL-F6, CTRL-SPACE, O-O, SLIPGATE, and V-Y make use of the glitches produced by the absence of anti-aliasing — a technique used to add greater realism to a digital image by smoothing jagged edges on curved lines and diagonals — in the game’s graphics engine, and its baseline screen resolution of seventy-two dots per inch. [7] Sections E1M1AP, I-N, and Q-L go so far as to reject the use of natural physics and instead submit the player to gravitational vortexes. Confronted by a game world laid to waste by technology, the player’s weariness seeks respite in both the destructive impulse and the placating images of visual abstraction. The ultimate failure is not on the part of technology, but, rather, our inability to distinguish the repose of nothingness from that of reconciliation.

This casts doubt upon the idea that JODI’s work, with its sardonic portrayal of technology and art history, is complementary to the hacking (or glitch) ethic in which the dialectic of abstraction generates technique ad absurdum such that technique itself becomes a datum: proof of the existence of an irrational totality that ought to be opposed. Perhaps, instead, untitled-game is unconsciously earnest. Like those born at the turn of this century, untitled-game is overwrought with anxiety about its own emptiness. This reflects the fear of one’s own emptiness. Are we up to the tasks of our own century? While JODI and their cohort rebelled against the ersatz institutionalization of the historical avant-garde in a way that merely affirmed its liquidation, today’s new generation of artists face both that rebellion and the original modern avant-garde as one single catastrophe. There are those who wish to revive the old tradition and those who seek continuity with the exhausted rebellion. While we must aspire to take up the tasks we have inherited from the original tradition and use that past to critique our present, we cannot simply return as though there has not been a historical break nor can we simply continue on the fumes of resentment. Perhaps from untitled-game we can learn this: that even they, that generation of scoundrels who despaired of the task before them, yearned to be free despite all their claims otherwise. Hope creeps out of a world in which it is only conserved within the promise of technical innovation, yet since everywhere is overwrought with technique, it crawls back to sleep. The only consolation that untitled-game offers is that the player can quit. Here, consciousness catches a glimpse of its own death, as if it secretly wished to survive, just as the player wishes to survive the cacophony of untitled-game. //

JODI. untitled-game: CTRL-F6. 1996-2001. Rhizome Conservation Fellowship

[1] Barbara Pollack, "JODI at Eyebeam." Art in America 92.3 (2004): 229 ; Mike Connor, "New Artist: JODI." Electronic Arts Intermix: New Works. Ed. Electronic Arts Intermix (New York: Electronic Arts Intermix, 2005), 5.

[2] Theodor W. Adorno, "On the Categories of the Ugly, the Beautiful, and Technique," in Aesthetic Theory, ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (London: Continuum, 2002), 45-61.

[3] Alexander R. Galloway, "Countergaming," in Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, (University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 107.

[4] Rosa Menkman, The Glitch Moment(um) (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2012), 31-32. See Menkman’s claim here: “The core of a work of glitch art is therefore best understood as the momentary culmination of a history of technological and cultural movements, and as the articulation of an attitude of destructive generativity. In short, glitch art practices are invested in processes of nonconforming, ambiguous re-formations,” 35.

[5] Geert Lovink and Florian Schneider, "A Virtual World Is Possible: From Tactical Media to Digital Multitudes | Future Non Stop," Future Non Stop. 10 Apr. 2003. Web. 01 May 2016.

[6] Kasimir Malevich, "Non-Objective Art and Suprematism" in Art in Theory. Ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Malden: Blackwell, 2003), 292-93.

[7] Rob Carter, Philip B. Meggs, Ben Day, Sandra Maxa, and Sand, Typographic Design: Form and Communication, 6th Edition (John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 328.