Poetry: Michael Heller

The Poetry of Michael Heller — An Introduction

by Norman Finkelstein

Michael Heller’s long poetic career can be understood as a sustained investigation into the substance of being, a quest to uncover what he ultimately senses to be hidden. He is a scientist of the spirit, a deeply learned philosophical poet who has demonstrated a lifelong suspicion of philosophy. A lyric poet who can reach ecstatically toward the starry heights via his studies of Buddhism and Kabbalah, he is also a dedicated craftsman whose insistence on verbal precision is derived from his close connections to the Objectivists and their empirically based belief that poems are constructed out of a commonly shared language. The intellectual urgency of his writing is balanced by its meditative calm. Thinking about his first encounter with the poetry of his mentor George Oppen, he observes “how little words counted against the strange unknowableness of the world. How everything of true depth to the individual struck me as being unnamed, and thereby unsayable even as its shadow in the form of desire swept across one.” And again: “If I understand Oppen correctly, the poet is caught between a philosophical sense of his or her craft and a religious sense of the mysteriousness of the world.”

This feeling of being caught between radically different poetic tendencies, however contradictory, inspires Heller continually. Born in Brooklyn in 1937, raised in Miami Beach, and educated as an engineer at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Heller had been working at Sperry Gyroscopes when he met two former students of Louis Zukofsky, including the poet Hugh Seidman, who remains a friend of his to this day. Through these connections, poetry seized Heller’s imagination. In June of 1965, he left his job and, with his first wife, took a freighter to Europe. They settled in the small Spanish village of Nerja, on the Andalusian coast, living there until September of 1966. Heller’s sojourn was based on a deliberate decision: he wanted to leave his familiar surroundings so as to see if he could transform himself into a poet.

As has become clear from the many books of poetry, criticism, and memoir that would follow this decision, Heller was growing increasingly attracted to mystery in the religious sense, though he has also never truly departed from the scientific education and rationalist worldview which shaped his sensibility. Or only partially shaped his sensibility: Heller’s great-grandfather David Heller was an important rabbi in the Polish city of Bialystock, and his grandfather Zalman, a rabbi and teacher whose presence suffuses Heller’s memoir Living Root (2000), supposedly authored a lost Talmudic commentary. Religious belief and, more importantly, ritual and commentary play out endlessly in Heller’s seemingly secular poetry. Is it any wonder that another of Heller’s cultural heroes is Walter Benjamin? Like Benjamin, he is a writer who constantly prowls the borderland between the sacred and the profane, the spiritual and the material. As he notes in Living Root, “Science had not rendered God dead. Rather, His death came from the believer’s hand at His throat, by the unspiritual nature of desperate spiritual clinging. In this game, not with God but with ourselves, He had become a horizon, ever receding as we presumed to get closer.” The practical result for the poet is simply expressed: “I, who am godless…seek for the precise word, the secular word, which would deliver.”

Deliver what? Deliver truth? Deliver us? For a poet engaged in composing “the secular word,” there is something disturbingly messianic about Heller’s vision. I am reminded of a passage in “Toward an Understanding of the Messianic Idea in Judaism,” an essay by Gershom Scholem, to whom Heller repeatedly returns. According to Scholem:

From the point of view of the Halakhah [Jewish Law], to be sure, Judaism appears as a well-ordered house, and it is a profound truth that a well-ordered house is a dangerous thing. Something of Messianic apocalypticism penetrates into this house; perhaps I can best describe it as a kind of anarchic breeze. A window is open through which the winds blow in, and it is not quite certain just what they bring with them.

Just as Judaism is a well-ordered house which needs an airing from the anarchic breeze of messianism, so too is the house of poetry. In Heller’s work, the building of the poem (one of his collections is called In the Builded Place) is frequently disturbed by such a breeze. His understanding of “The Uncertainty of the Poet” (the name of a 1913 de Chirico painting which becomes the title of a Heller essay) informs everything he writes. The measured pace of his verse and his careful examination of the violent history of modern civilization are undermined by the question which imposes itself again and again: “I don’t know where spirit is, / outside or in, do I see it or not?” (“Eschaton”). The result is an “Omnivore language, / syntax of the real, riddling over matter, // more difficult to ken / than the Talmudic angelus” (“Lecture with Celan”).

Heller’s “omnivore language” is shaped variously, from the warm, easygoing stanzas of “For Uncle Nat” to the tightly bound couplets of “Sag Harbor, Whitman, As If an Ode,” to the more abstract, disjointed prose statements of “At the Muse’s Tomb” and “Mappah.” His stylistic range is remarkable, but “the salvaging uncertainties” of his restless, turbulent thought and his linguistic self-awareness remain constant. This phrase is from “Commentary is the Concept of Order for the Spiritual World,” a poem in which each line is riven by a space, creating a caesura not only in rhythm but in thought itself. The poem ends with Heller’s experience of

a sense of world-depths that no longer crowd the mind,

thus a rich compost of the literal

of what is said.

And then might not our words loom

as hope against fear for near ones,

for their gesturing towards a future?

Cast in the conditional, hovering in uncertainty but still hopeful, these lines exemplify Heller’s vision of how language, how poetry, always gestures toward the future, serving as our guide.

On alpert+kahn

For over twenty years, I have been drawn to the mysterious artworks and installations of alpert+kahn, (the signature name for the intense collaborations of the artists Renee Alpert and Douglas Kahn). Almost from my first exposure to their projects, I had a strong desire to add yet another layer of collaboration in words, which resulted in the visual poetic sequence Dda, based on their own response to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. What struck me then and continues to enrich my experience of their work is the deep, resonant architecture of their pictures, the pristine formality of their structure, the constant arrangement and re-arrangement of a limited number of “real” elements, their vocabulary of factory ready-mades, light bulbs, rebar, piping, gantries and, most recently, the plastic sheet draperies that hang over construction sites, only, in the case of alpert+kahn, not to wrap but to lay bare the nature and textural feel of the wrappings in their artistic and cultural implications.

alpert+kahn’s works seem to exhibit a strangeness that can barely be verbalized even as they evoke forebears as varied as Charles Sheeler’s hyper-industrial landscapes or the curious, contemplative resonances of de Chirico’s nearly empty plazas and streetscapes. What is unique to their work is the self-signifying nature of their images. Their “if” and “bird city” series, for example, seem to convert the pathos of a lost American landscape into a kind of contemporary glyph or rebus, the “evolution,” of their manipulation of image and coloration by which, to use their words, “a bucolic rural green manufacturer” is re-imagined as a “a mega-industrialized complex gone unrestrained.” The social commentary is a kind of aura implicit in such pictures, but what strikes most powerfully is a haunting stand-aloneness as beautiful and as bleak as a Friedrich Church iceberg. Particularly striking are the foreboding backgrounds on which the discrete elements are placed. No one has ever seen “skies” or backgrounds quite like those that set off the objects, nor did any mix of colors so eschew the nostalgia of sepia. The viewer is both outside and in, drawn by a sense of loneliness, of longing in which the depth of field creates the paradoxical feel of nearness and distance. The originality of their artistic idiom, without ever contemplating a false illusion or “deceit,” transforms that very American pathos into prophecy. In many of their pictures, light, maybe sunlight, is streaming in from somewhere, illuminating and making tactile their impressive vision.

—Michael Heller

A LOOK AT THE DOOR WITH THE HINGES OFF

1

In white suits, on a white-washed terrace, Pound and Fenollosa sat at a white painted wrought iron table with a glass top, drinking a milky white drink, ouzo perhaps or a mixture of milk and water. At that time, Fenollosa had grown a rather large black moustache which stood out against the whiteness of the scene like one of his inimitable Chinese characters.

2

In white suits, pagination permitted, the terrace washed in white paint, a light rain had fallen, which now the heat of the sun, pulsating behind the clouds, changed to steam. Ouzo was brought out by the waitress, a young girl with very white skin whose dark eyes hung in the white space of the scene like two dots in the negative of a photograph taken through a telescope trained on Sirius and Canis.

3

In control of the whites, Franz Kline claimed he was not a calligrapher, painting the white portions of his later canvases with as much concern as he showed for the blacks. Canis and Fenollosa would have gotten along well together.

4

We have a problem with white. It is the grace of saying it. Something we like — a flash of color, an absolute aimlessness to our intensity — the world will suffer less.

5

At every point a node of energy clung to the white wool of her dress. It was all very sexy.

6

The grand themes demand a certain silence, a sense of quietude which precludes pompous utterance. Here, my dearest, the ubiquity of the world in clean white sheets.

from here to there, of progress, archival pigment print, © alpert+kahn.

THREE BAR REFLECTIONS ON JOHN COLTRANE

The language of New York has changed a bar and restaurant

scene to two women talking of lovers black and white,

liberal lovers. She says she saw a man on the street

roughly of his features and mistook the man for him but

that the man was not his color. She says to her friend,

she is color-blind, she says she knows all about him.

*

He: a hunched back and boiling red face; beside she: small

and shriveled. Both in the booth, their ugliness uglier

for their awareness. This couple getting thru the world.

A fact imaging a deeper fact. As with only the weight

of notes the song is dragged down thereby amid detritus

and effluvia. Against the sweetness of creation attitudes

are posed because it drives back to the core thru all

the secret lives dreamt of, rancorous and jealous of

what is incomplete or unfulfilled overwhelming the music

unless love saves it.

*

History is a joke. Personal history: unfunny.

Knowing everyone to be serious when sick and banging

on the bed for some stranger, but that he should be

like ourselves. And come get drunk or delirious, falling

into someone resembles us. On this, the heart realizes

itself meaningless — its words have moved off beyond

their meanings, as in the music, the whorls of sound

are an eternal trope — an eternal equivalency. Not to be

admitted to my world — I come to his.

reframed, of progress, archival pigment print, © alpert+kahn.

PHOTOGRAPH OF A MAN HOLDING HIS PENIS

for Michael Martone

World o world of the photograph, granular,

Quantumed for composition in the film’s grain,

But here blurred, soft-toned and diffuse

Until the whole resolves into an ache, a

Chimerical, alchemical flower, a pattern

Against pure randomness.

As though the process itself exists to mock

What is discrete, is singular. Dot leans on dot,

On the binary of only two can make of one a life.

And the myth is partial,

A dream half of need confused with desire.

I too live out this fear, this shadowed aloneness,

The white hand’s delicate hold where the genital hairs

Are curled, the groin become a hermitage, a ghastly

Down of our featherings . . .

And the texture is bitter, bifurcate,

A braille of flesh

From which a ghost is sown.

between, if, archival pigment print, ©alpert+kahn.

IN A DARK TIME, ON HIS GRANDFATHER

Zalman Heller, writer and teacher, d. 1956

There’s little sense of your life

Left now. In Cracow and Bialystok, no carcass

To rise, to become a golem. In the ground

The matted hair of the dead is a mockery

Of the living root. Everyone who faces

Jerusalem is turned back, turned back.

It was not a question of happiness

Nor that the Laws failed, only

That the holy or sad remains within.

This which cleft you in the possibility

Of seeing Him, an old man

Like yourself.

Your last years, wandering

Bewildered in the streets, fouling

Your pants, a name tag in your coat

By which they led you back,

Kept leading you back. My father

Never spoke of your death,

The seed of his death, as his death

To come became the seed, etc. . . . Grandfather,

What to say to you who cannot hear?

The just man and the righteous way

Wither in the ground. No issue,

No issue answers back this earth.

coming soon, if, archival pigment print, © alpert+kahn.

FOR UNCLE NAT

I’m walking down 20th Street with a friend

When a man beckons to me from the doorway

Of Congregation Zichron Moshe. “May I,”

He says to my companion, “borrow this

Jewish gentleman for a moment?” I follow

The man inside, down the carpeted aisle,

Where at the front, resplendent in

Polished wood and gold, stands

The as yet unopened Ark.

Now the doors slide back, an unfolded

Promissory note, and for a moment,

I stand as one among the necessary ten.

The braided cloth, the silver mounted

On the scrolls, even the green of the palm

Fronds placed about the room, such hope

Which breaks against my unbeliever’s life.

So I ask, Nat, may I borrow you, for a moment,

To make a necessary two? Last time we lunched,

Enclaved in a deli, in the dim light, I saw

A bit of my father’s face in yours. Not to make

Too much of it, but I know history

Stamps and restamps the Jew; our ways

Are rife with only momentary deliverance.

May I borrow you for a moment, Nat. We’ll celebrate

By twos, the world’s an Ark. We’ll talk in slant,

American accent to code the hidden language of the Word.

expanse, if, archival pigment print, ©alpert+kahn.

LECTURE WITH CELAN

How many know

the number of creatures is endless?

So many know,

only a gasp in their questions is possible.

All that fullness —

of wounds that won’t scar over,

pain’s grille work

persisting in the memory.

What sets one free

within the sign and blesses the wordflow

without barrier?

Not literature, which is only for those

at home in the world

while air is trapped in the sealed vessel,

contained in our

containment, our relation to earth.

Omnivore language,

syntax of the real, riddling over matter,

more difficult to ken

than the Talmudic angelus. Thus what black

butterflies of grief

at this leaf, at this flower? Already you

have moved over ground

beyond past and future, into a strange voicelessness

close to speech,

both dreadful and prophetic — all else utility

and failure. And now,

the work builds to a word’s confines,

to a resemblance of lives

touching the history of a rhyme between earth and dying.

division, if, archival pigment print, ©alpert+kahn.

STANZAS AT MARESFIELD GARDENS

The dream manifest as ruin. He feared forgeries

and eliminated suspicious items from the collection.

Still, after his death, many fakes were discovered.

The ruin manifest as dream. He deployed figurines

of ancient deities at which he gazed. Those with

half-turned heads he positioned over journals.

*

His antiquities: the Buddhas, the protectors,

the instructive voids he saw in Roman jars

half-filled with a crematorium’s ash and bone.

Those heaps! Their inimitable deserted air —

out of that clay and back to clay, adamah!

What to will from these shapeless mentors of speech?

What utterance lifting powdery blackened grains

to something human? What voice to throw out

against those other gods always in miniature in their cruel

presiding, in their fixed vesseling in bronze and stone?

Time-maimed fickle Isis-Osiris, noble Avalokitesvara

whose raised hand is a gesture to the named and unnamed

who stand guard over the scriptor. And there too,

are the onyx-faced ones, scowling at heresy and betrayal.

Do not look askance; do not miswrite! Thus, to hear

each persona in the room utter form, in babbled hope

of words poured back over the eons, in hope of words

given to gods as sacrifice, as exigent futures

of sound, divinities claimed in flawed obeisances.

*

The collection was a dream unmarred by forgeries

he ruthlessly eliminated. Manifestations of half-turned heads

he thought of as ancient deployments, listening to patients

as though gazing on collections of ruined forgeries.

He deemed these manifestations as collections he deployed.

Half-turned dreams of patients gazing toward ruins,

of ancient figurines he looked at ruthlessly while journals

under deities lay open manifesting as his collections.

fracture, if, archival pigment print, ©alpert+kahn.

AT THE MUSE’S TOMB

After Reading

The long eerie sentences were fates as the savannahs of Georgia and the Carolinas were endless stanzas in pine and swamp water.

Searches were made among the word-habitats that mattered, consonances of landscapes and self, half-geographies contoured from remembrances, shadowed and opaque.

The rest, the unexplained, the transparency, the mirrors and the dust, were to be talked away as dreaming.

The investigation missed horror.

Yet no one complained, preferring to imagine a pale language, paler than a linen tablecloth or the desert’s unlit night.

Poe’s white Baltimore stoop mounting to a door.

Form

Nothing to ennoble the passion for measure and number, for the hard precincts of form, that uncanny love, surely as indictable as any great crime or gratuitous enormity.

Yet, with one’s attention span, the mind wandered out, a weighted thing to be pushed forth on a cloud of moistened breath, to soar and curl itself about a street or a city.

Hungerings occurred amid the silted isobars of hope, in love’s calms and tempests, sloughs of logic gone astray which had left us open to chance and to a desiring to persist.

The self’s tellings were another moon haunting its own sublunary. It sought itself as a name high over soil it had made, rocks, cities, isolate worded beings.

Mnemosyne

O Mother memory, yes!

I had visited in Spain, did my Goya-walk to the nth, but it barely got me to Lorca.

The duende, mysterious visitor, came and went.

The dead war ravaged among villagers.

And suddenly the muse was no longer a headstone stippled with palabras.

The Local

Actually, by accident of birth, I was born to homelessness and nothingness.

Later I opted for the local, for the 63rd A.D. election district and its bands of refugees who vanguard at the doors to ATMs.

Also to what the city advertises, gunk or hair-gel, the stickiness of lost meanings, of signs secured by ripped awnings, foreclosures on the dark, dry pavings of a night skittish with deaths.

Beyond words’ portals, I was always turned back, a bewildered Orpheus, city gentleman to Eurydice, an Amphion who gathered up stones into another hell-heap.

And now I feel a bit sickness-haunted, peering at the ineffable from an alley.

Our Time

Media voices over-wash all, blurring the inevitable: Psyche’s credit-card sorting of the selves into collectives.

From the great engarblement, words are lifted out, and, in the current lexicon, crowd aside columns of pictures, taking one past new literals for contemplation among metonyms of blank.

Ghost

I was thinking about memory again, writing its letter home.

Before she died, her face, her favorite objects, etc.

Breakfasts were sweet, even . . .

On the table, the plunged gold plate of the bell on a silver creamer.

Someone left a world in it, a layer of puddled whiteness

resembling a page, viscous, absorbent, richer than the néant

Mallarmé inscribed on.

Never One

Because it is almost sound, it was meant for sharing.

We watched together the sun pour in the window,

motes of light on glass and wood.

Who was home to this homeless light?

Together we dreamt of transports, of residences as glints off mica-ed rocks, centerless sheens bouncing from the frozen lake.

One felt the very slightness of being, almost validity’s dusting up.

Yet also love, which hid us from the fiction’s glare.

Pointless to ask for the addressee of desire.

Or that the mind misspoke its sonic phantoms and conjured the self which erred and brought us to this place.

Aphasia

And now, the demiurge possesses a lightness, a wet nuzzling of hope blind to the part played by the geometer’s art.

Bleached one, O muse, I think of you, your silences where the throat catches on emptiness, that free flight into the wordless.

O teacher, the sky’s light is fading, and I have sought that one place, speechless to the moon, an omen blossoming at its own edge, a bizarre portraiture in the rush of things portentous.

Bleached one, what was strategy?

What was truth?

The plangent lucidity, the glass through which the light flowed.

at the intersection, the sum of some parts, archival pigment print, ©alpert+kahn.

SAG HARBOR, WHITMAN, AS IF AN ODE

I

And so again, to want to speak — as though floating on this world —

thoughts of Sagaponak, of Paumanok, “its shore gray and rustling,”

To remember late sun burnishing with a pale gold film

the feathery ghosts of blue heron and tern, of that same light

furrowed in the glyphed tracks to bay water. And at night,

to scrape one’s own marks in sand, a bio-luminescence underfoot

by which we playfully signaled, as the heat of bodies also

was a signal to turn to each other in the guest house buried

in deep sunk must and trellised scents. As though, again, to be

as with mossed graves which, even as they lie under new buds,

are worn and lichened, chiseled over with letter and number,

entrapped, as in the scripts of museum words, trypots and scrims.

And so, like whalers, whose diaries record a lostness to the world

in the sea’s waves, to find ourselves in talk’s labyrinth where

the new is almost jargon, and we speak of lintels of a house

restored or of gods who stage their return at new leaf or where

pollen floats on water in iridescent sheens.

II

But also now, to sense mind harrowed in defeats of language,

Bosnia, Rwanda, wherever human speech goes under a knife.

And to be unable to look to the sea, as to some watery possibility

which would break down the hellish rock of history that rides

above wave height as above time. Strange then, these littorals

teeming with sea life, with crab and ocean swallow. Strange then,

to walk and to name — glad of that momentary affluence.

And so to find again the vibratory spring that beats against

old voicings, old silences, this waking to those fables where

new bees fly up, birthed spontaneously from the log’s hollow,

to hear again the Latinate of returning birds keeping alive

curiosity and memory, as if the ear were to carry us across hope’s

boundary, remembering the words: Now, I will do nothing but listen!

amongst the ensiled, the sum of some parts, archival pigment print, © alpert+kahn.

“We can only wish valeat quantum valere potest.”

for Armand Schwerner (1927-1999)

The dead were to be interrogated

beside the meaning “sign.”

We looked in vain for the words

“cow,” “sheep,” “pig,” etc.

Hahriya meant not only “to comb,”

but also to touch affectionately,

to stroke, to caress, to fondle —

also to tickle and incite,

(and in the sexual sense, to be

caught in the dreams of Puduhepa).

On many days, we admonished

ourselves for our arrogance.

Much of the vocabulary consisted

of words hidden behind logograms,

indicative of first things,

the need and desire to speak,

to bring back the body. Thus,

who to propose a given meaning,

who to vouchsafe its reliability?

The dead did not need our wisdom.

One context would have allowed the idea

“to hurl, to shoot,” another “to dismiss,

to throw, to push aside (as a child).”

The word stems were clearly uncertain.

In the documents, eribuski, the eagle

was made of gold, and flew over

without conjecture. But elwatiyatis,

with its many syllables, meaning unknown,

appeared again and again in connection

with the word for “billy-goat.”

Questions remained. The void offered utterance.

We thanked the impenetrable silence for permission,

for deepest gratitude. We bowed to

the acrid muteness of another world.

Take esarasila (the context does not

give meaning), but we pondered its sound

on air, for we had been given the word as though

incised in stone, as glyph or diadem, as memorial.

Esharwesk translated, not only as “blutig machen,

mit Blut beschmieren,” but “to become, to turn red.”

Layers were many. And here, face it, we sought

another’s breath, mother to our language.

We sought sound as resurrection. With this,

we were beschmieren. The gold eagle flew

toward a reddened sky, the word stem not always clear.

But better not have attempted the translation?

Halkestaru, “Watch, night-watch,” was actually

two words. Difficult to have taken any of this

as causative. Still, all we wished for

was that our efforts be harnuwassi,

“of the birth stool,” or that we would be led

to hantiyara, a place in the riverbed where fish live,

a “backwater.” O Valeat quantum valere potest.

No work for the self, only lust for lost voices,

fellow hapkari* (pairs of draft animals) . . .

ON A PHRASE OF MILOSZ’S

He is not disinherited,

for he has not found a home

stretch, rapt, archival pigment print, ©alpert+kahn.

He has found vertiginous life again, the words

on the way to language dangling possibility,

but also, like the sound of a riff on a riff,

it cannot be resolved. History has mucked this up.

He has no textbook, and must overcompensate,

digging into the memory bank if not for the tune

then for something vibratory on the lower end of the harmonics.

He’s bound to be off by at least a half-note — here comes jargon, baby —

something like a diss or hiss. Being is

incomplete; only the angels know how to fly homeward.

Yet, once the desperate situation is clarified, he feels

a kind of happiness.

*

Later, the words were displaced and caught fire, burning syllables

to enunciate the dead mother’s name.

(Martha sounding then like “mother”)

Wasn’t it such echoes that built the city in which he lives,

the cage he paces now like Rilke’s panther?

He was not disinherited.

He was not displaced

He is sentimental; hence he can say a phrase like his heart burst

The worst thing is to feel only irony can save

The worst thing is to feel only irony.

ESCHATON

I don’t know where spirit is,

outside or in, do I see it or not?

Time turned the elegies

to wicker-work and ripped-up phonebooks.

All that worded air

unable to support so much as a feather.

*

If there’s hope for a visitation,

only the ghosts of non-belonging will attend.

And now death is slipping back

into the category of surprise.

I sit up at night and pant, fear

half-rhyming prayer--

self beshrouding itself

against formlessness.

In-breath; out-breath.

Aria of the rib-cage equaling apse.

Skull, the old relic box.

INTO THE HEART OF THE REAL (from Beckman Variations)

-- Abtransport der Sphinxe (Removal of the Sphinxes), 1945

The Sphinxes have beautifully outlined breasts, and they stand proudly on their taloned feet. And their taloned feet rest proudly on stone pedestals. Wood for crates is stacked nearby, and a sister bird has taken flight. Each sphinx, from its platform, tells a seductive tale. Each one makes a liar out of one of the others. Whether on the pediments of stone or placed for shipment on the tumbrels, they insist on whispering silky words in one's ear. Little breezes are stirred by their sibilant words, little swirls that are worse than typhoons or tornadoes. Big storms, hurricanes are the exhalents of the world's turning, of massive pressure gradients at the poles, knocking down buildings and flooding streets. But the tiny voices of the sphinxes enter through the ears like silk worms; each weaves a gummy dream to the bones of the skull as though it were a shadow on the wall of Plato's cave. Each tiny voice blends in with the sound of the real, urgent, unappeasable. There's an official monitoring each skull who, even as he listens, is already insisting on the dream's removal. The sphinxes must be carted off. One thinks that the officials would organize deliveries of this nature in secret or at least elsewhere, but no, I have seen each one at the embarkation point eagerly straining on a rope, gleaming with sweat, pulling the crates toward the outgoing barges.

FALLING MAN (from Beckman Variations)

-- Abstürzender (Falling Man), 1950

It is great to fall, it will be important if I plunge

this way, as it would not be great to be entangled.

But if I plunge head down, feet clear and don't catch

on a building ledge, I will swoop past the structure

blazing in flames on my right, go past the open window

to my left where one sees some compact of love, violent

and contorted, is acted out. I admit, it is great to fall, great

not to fear snagging on the buildings to the right or to the left,

wonderful to fall free from clouds swirled in turbulence,

passing toward the blue of the sea where a small boat sails,

where gulls fly like avenging angels, and the momentous inevitable

wheel of life and death has a benign dusty shine. I am going down,

dropping toward the cannibal plants, the cacti and Venus fly-traps,

unnamable greens and jaundiced yellows. Down.

COMMENTARY IS THE CONCEPT OF ORDER FOR THE SPIRITUAL WORLD

the capacity of illumination, rapt, archival pigment print, © alpert+kahn.

If these streets, this world, are the arena,

then each person passed, each bidding building

unentered, leaves room for ruminations

illumined by an edge, a back-lit otherness

positing a liberty to think or not think

an idea, to fly up outrageously

or swoop earthward, toward a grand passion

with a hawk’s fierceness, talons extended,

and yet, for a second, to hesitate—

If we are always outside the precincts of power,

even our own, and so imagine

(for instance) the possibility of a tyrant,

helpless for a moment before sunlight’s brilliance

on rolling grass, if we no longer

keep to our assigned faith as Job’s messengers,

each escaped alone to tell thee,

then the deep flaws, the salvaging uncertainties

in the world’s overriding syntax—

love of self, for instance, migrating to love of another--

or those records of an observing eye

noting the lichen’s patch on the rock face,

the waters slow eroding of the boulder,

(such witness an ongoing work

of resistance), wouldn’t this proclaim

that he is most apt who brings with himself

the maximum of what is alien--

a sense of world-depths that no longer crowd the mind,

thus a rich compost of the literal

of what is said.

And then might not our words loom

as hope against fear for near ones,

for their gesturing towards a future?

MAPPAH

This brocaded cloth is nothing in itself, neither real nor unreal, woven with an edge that is no edge.

No one can safely say where the sacred leaves off, where the profane begins.

The teacher remarked that to regard the earth as the shrine-room floor is enlightenment.

The sheath was slipped from the Torah to reveal the scrolls, the Torah laid upon its stand, the scrolls were opened for the day’s reading.

Some believe a god keeps the process going. Others, that if there is just one god or many, they can want nothing of us, else how could they be gods?

I’m not sure of a god’s existence, even as I shy away from those who insist they keep company with one.

But if a god wants the person’s marrow, as with Job, then the visible and invisible ways by which a god manifests are extensions of a hunger.

Which is why such weight is given to the delusions that make us happy. Is it madness to kneel before the sea, to say a prayer over something like a piece of hard candy?

Yet everything that is the case continues, and I am left with a suspicious sorrow that we grieve neither for truth nor falsity.

Someone lifts and folds the cloth, someone follows the Hebrew with the yod, the sculpted finger cast in gold. Davar and davar.

Signs of revelation are shown forth, the dulled angel of history, our brighter angel of catastrophe.

Let this be put another way: the cloth that shielded the Torah from light shielded light from the Torah.

Remember in historic Paris, the pause before the mappah in its glass case, the embroidery, the traceries of dedication to the patron’s daughter, lamé and beadwork?

Remember the heartbreak, the cry to wake the dead and restore what has been lost?

During periods of calm, an adequate vocabulary was found among cynics.

But introduce a little danger or show people running for their lives, and how quickly attention focused on words like bread or child.

One thought in afterthoughts, of the saved, of the living. So it went on.

After disaster or terror, each declension in the name of a god became fixed.

In the fires, the weavings burned with the parchment.

Smoke rises, blackens.

Let this be put another way: the cloth that wrapped the Torah in darkness shielded the light from the dark.

Let this be put another way, let this be put differently, the wish to call out.

AFTER BAUDELAIRE’S LE GOUFFRE

He knew the syllogism

could not explain

why one day

slammed into the next,

or why it hurt

as much to be alive

as knowing something

bad awaits you.

Why awls of doubt

painfully nicked

a groove in thought,

why hopes deceived.

The syllogism

could not explain

those green islands of desire

that lie deep inside.

No lines of verse

in the logic’s rationale

to carry him off, nothing there

to puff out ego’s billowed sail.

The syllogism paid no attention

to all the half-heard talk,

to the nonsense of spun-out thought

that only entertained.

Thus was the abyss

carried within,

setting my hair on end,

while winds of fear passed frequently.

It hurt as much

to be alive

as knowing something bad

awaits you.

He gave over night

to Morpheus,

to seductive figures that startled

and made sleep suspect.

Dream and nightmare insisted:

death really

wasn’t good enough for us.

He wasn’t sure:

were we mortal or immortal?

That’s why it hurt

so much to be alive,

knowing something bad

awaits you.

HIGH BASIN

(from Tibet: A Sequence)

To collect myself there in the mountain’s cut: to bathe in the self’s pool:

all its stories-of myself, to myself—gathered, and led into runnels,

to flow from on high to low, flux without root or rootedness,

useless to name, useless except to surrender and admit

the shame of wanting the unknowable, incessantly casting and retrieving the bait

of the ego, as though before a watershed teeming with life.

The gods must be fond of laughing. Your warriorship enclosed between

a helmet of sky overhead and the rock’s amphitheater, armor hard from its hollowing,

plaything of the self’s interior winds.

But to heal again I turn to your example Tibet, rich with adventures.

Can I imitate your sacred lake, Yam dok-Tso, outlet to the West?

Doubled lake—lake—twice set in its liquid nomination, word/thing

of mind, only mind, distilled as though a secondary water.

Can I also, by hyperbole and sequence, journey there?

Transport from level to level,

to move with high compassion and swelling O calculator

to be—to the ninth power, for all beings,

and almost to the centuple fold, to the crescent (growing) number,

without denial.

And also following toward infinity.

bird's folley, bird city, archival pigment print, © alpert+kahn

RE-SEARCHES

Our grim cruel machines. Read Milton on Euripides

–-the tragedian’s verse in Electra charmed Sparta

to spare Athens, but then there’s Milton, his

On the late Massacre . . . asking God to avenge

“Who were thy Sheep and in their antient Fold”

whom the Piemontese “roll’d Mother

with Infant down the Rocks.” This grimy machine

of poetry, portioning off the logos proclaimed divine.

When did poets not live in destitute times,

nourished and nuanced on decades of bloody

adventures? Pull down thy vanity. IT COHERES,

the works of man in the work of lyric salve, solvent,

no key to unlock hidden bliss or faintest hope.

No exemption for that poet who wrote

of the messiah arriving on a tank, or that other

who began each pitch into the doom machine

with a pastoral, urban in its love of sunsets

through bridgeworks, music of jazz and blues,

city scene spiraling from streetscape

to the planes that blew out skylines and littered

plazas with those who jumped from heights

--medieval, a few speared on metal palings

or the trees’ forked branches. New strange fruit.

Yet no logic nor words could divide us, plein air,

nor would Cartesian symmetry balance the sharp passions

of our bodies. We sang, we sang our masking music

flowing cleanly through the self; we counter-sang abide

with me, kol nidre, Om chant, Blake’s psalm, all Kiddush, kid-ish.

COLLOQUIA

I.

“World, World,” you wrote,

as though martyred to the visible,

the words one chose

would have to say it.

If the famous rosy fingered dawn

existed, it existed to be proclaimed,

as did the catalog of phrases to embrace,

sheer gorgeousness and vibratory

power of words

to upend those imprisoning

geometries of the conventional.

*

To articulate mind’s paean

imagine the silken net of her,

the sheathed stone of towers

we walked around--

word, words to world, world--

reluctantly including the age’s

horrors we read about.

Love and desire as possibilities,

as possible suppressions

in a world raped by its ideologies.

Did relief come as compensation

in the words?

What to say for the rock’s display of striations

emblazoned above a flowing creek,

the deliberation describing the insect crawl,

its “chitinous wings,” that reminded you

of Pound’s wasp, and in that moment,

you forgave him his politics

(thus sharpening some issues at hand).

Best, you said, to be “unteachable.”

Yet so many lived blind-sided by the digital algorithms

of their tribes, arrogant in their insistence and consensus,

the bard’s finikins strewn across a wasteland.

Thucydides reminding us, “in evil times, words changed

their common meanings, to take those now given them.”

And you said, the problem was failure, no prominence,

only the ditch from which all was seen. “World, World,”

I believe you meant something like the cosmos.

“There is something to stand on.”

That was as close as one should come to belief.

II.

And I remember the teacher’s sadhana proclaiming:

This world, the trees, the greenery, the Great Wrathful One,

you incite, you are the irritant from which

love and hate spring. And I remember

the nights I broke free --eye at the reticle

open to dark skies, charts laid on the table,

dome under dome: “say I looked at the stars/say

there was love in the sky/but it wasn’t enough.”

Youth’s dream: to be of that chorus. There it was

and this in which, however entrapped,

I gazed at an open starlit field, pristine immensities,

thoughts pliable as the wind swirling around objects

—a little pain, a little bother—one’s mind fumbling,

finding only its anguish real. Redemption: an image

on a reflecting mirror . . .

III.

The world is the case (and it is beautiful), thanks LW.

The world is the case, surely the praise poet has a case to make.

The world is the case encased.

Seen from outer space.

Ice orbed.

IV.

—descend so that you may ascend—Augustine

Trees darkening the ground. Constellations overhead.

Midway, you’d want to go into the subject--then I’d go.

We’d call it prayer if you like.

We’d both desire to walk on, to be happy.

Not much talk but for an occasional comment

on “the compost of history.”

And I did make something of a prayer for myself,

I called out: Dante, help me with a four-fold allegory,

one that begins with a beast, a griffon or Sphinx

and works its way to joyful singing, as in Purgatorio,

pinkscape, remnants, archival pigment print, © alpert+kahn

“in exitu Isräel de Aegypto,” that “anagogically”

speaks of souls who from the Shoah did not escape

but rose in ashes to somewhere else, sanctified

from corruption by our inability to forget, and I meant,

my dear guide, let’s go no further, but turn at this point

and backtrack along the bolgias, for to “go up” is to be perfected,

even if to walk past the condemned as they suffer reminds them

of their shame. It was by this way, past the limbo of ancient poets,

beyond their need to traverse desire, that we would return

to the dark wood from which youth makes its descent,

this time into age. Here, where leaves lay crushed underfoot

and autumn awaited winter, we would emerge into a dark expanse,

and name the liminal objects outlined by the stars dim light

as though they were signs of the visionary.

equilibrium, remnants, archival pigment print, ©alpert+kahn

alpert+kahn exploit photography by recycling and manipulating photographic images. For example, reconstruction occurs by recombining photographs as well as using selected parts, enlarging areas, drawing from the original images. The result is an abstracted assemblage where the parts are divergent from the original photography.

As a student at the University of Washington, Renee Alpert was encouraged by Jacob Lawrence to pursue a career in art. In 1984, she was awarded an MFA from the Yale School of Art and the Helen W. Winternitz Award. After graduating from Pratt Institute with a degree in architecture, Douglas Kahn worked for Marcel Breuer and Richard Meier before forming his own firm. After leaving New York in 1980, he showed as a fine art photographer and worked as an architectural photographer. Renee Alpert and Douglas Kahn started collaborating as alpert+kahn in 1987 in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Their work has been shown at The Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, The Cinema Institute of Moscow, as well as Fine Arts Center @ Cheekwood, and the Roswell Arts Center. Since living in Colorado, they have shown during the Month of Photography, The Colorado Photographic Arts Center, Goodwin Fine Art Gallery and The Art of the State at the Arvada Center for the Arts. They are in numerous collections including Gulftech Corporation, JUXT (Holland Partner Group), Seattle, Jane Reese Williams Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe, NM, Polsinelli Law Firm, Russian Art Photographers’ Union, Moscow, Russia plus private collections.

A SKÁLD’S GALLERY:

Michael Heller

Note: Twenty-three microseconds out of the millions and millions making up my 84 years, out of the thousands on film, on the memory chips. So much left out. Spliced it for Caesura, I hope it will be of interest.

1) Great grandparents on my father’s side: David Heller and his wife Fanny, Bialystok, Poland (1890s). He was a well-known rabbi in the city, rumored to have opened his home to the poor. This picture reproduced in my Living Root: A Memoir (SUNY Press, 2001). I can find almost no photographs and memorabilia of my mother’s family, the Rosenthals, who came from Rumania.

2) In our Pulaski Street, Brooklyn brownstone home (1941?). It is still standing, surrounded by leafy trees. Sequence left to right: my older brother Bummy, my sister Tena, my father (uncharacteristically in casual clothes), me (uncharacteristically wearing a tie) and my father’s brother, Uncle Nat. See “For Uncle Nat” in the poem selections.

3) Brother (me) and sister Tena, Peekskill, NY. Summer rental 1945, the A-bombs were dropped on Japan in August, WW II ended, and my mother wept with joy that her younger brother was coming home from the European front.

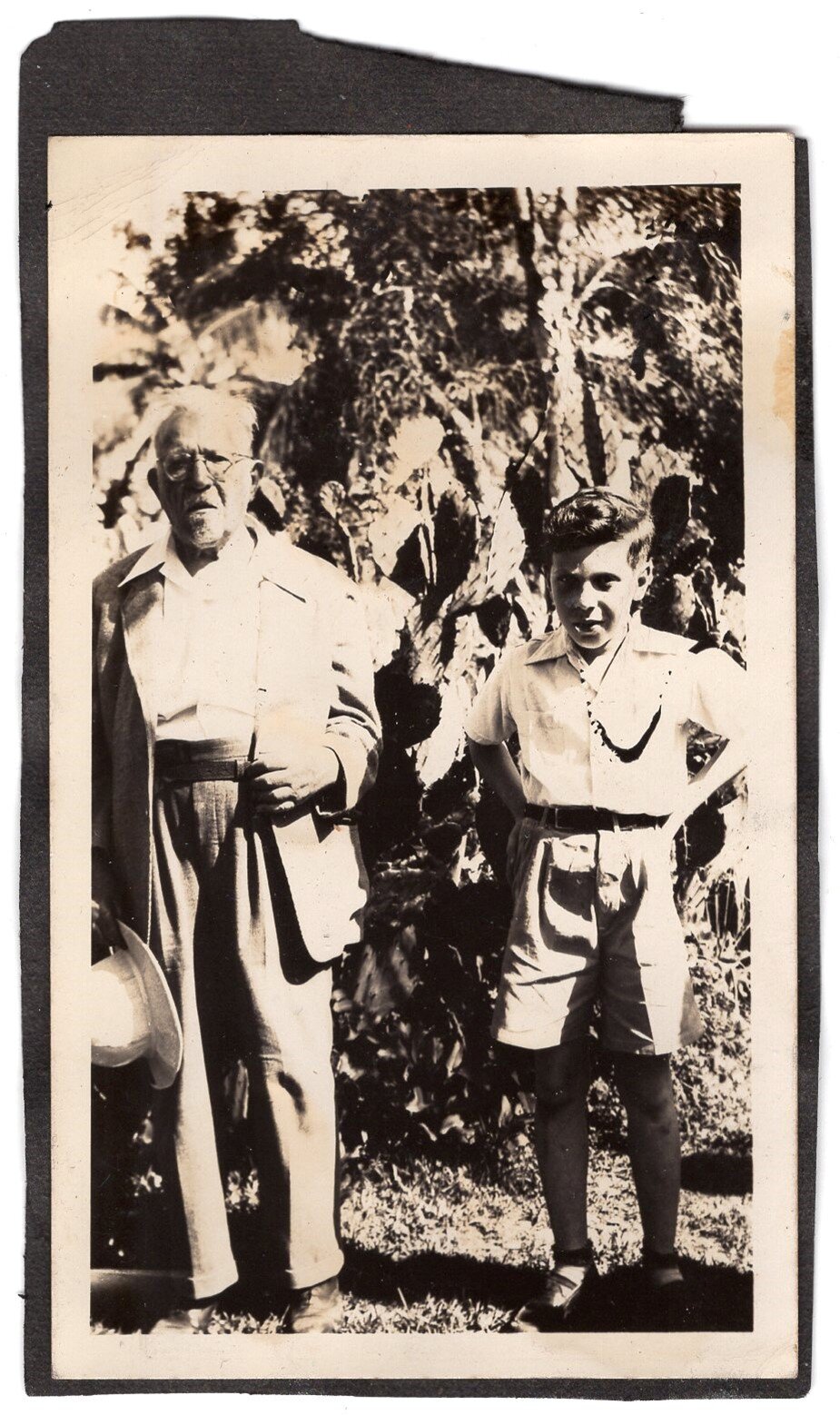

4) Miami Beach, 1946. My grandfather, Rabbi Zalman Heller, and me in Flamingo Park. He came from Brooklyn to visit for the Passover. The seder, held at an oceanfront hotel, struck him as trivial and irreligious, so, amidst the crowd in the dining room, he conducted his own ceremony at our table.

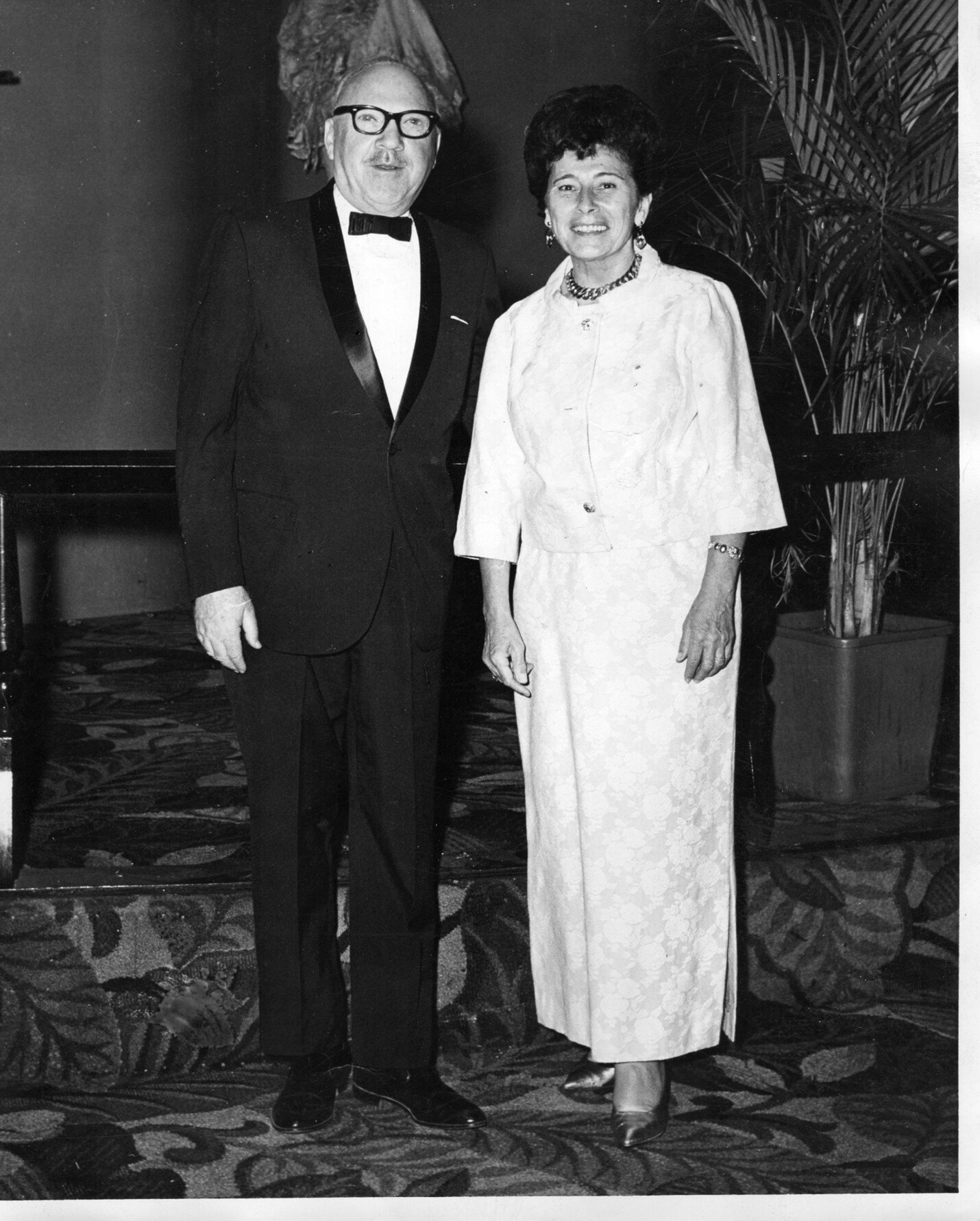

5) My parents, Pete and Martha, out on the town (Miami Beach, Florida, 1950s). In 1979, I had the tux he wore altered for my wedding reception with Jane at the Algonquin.

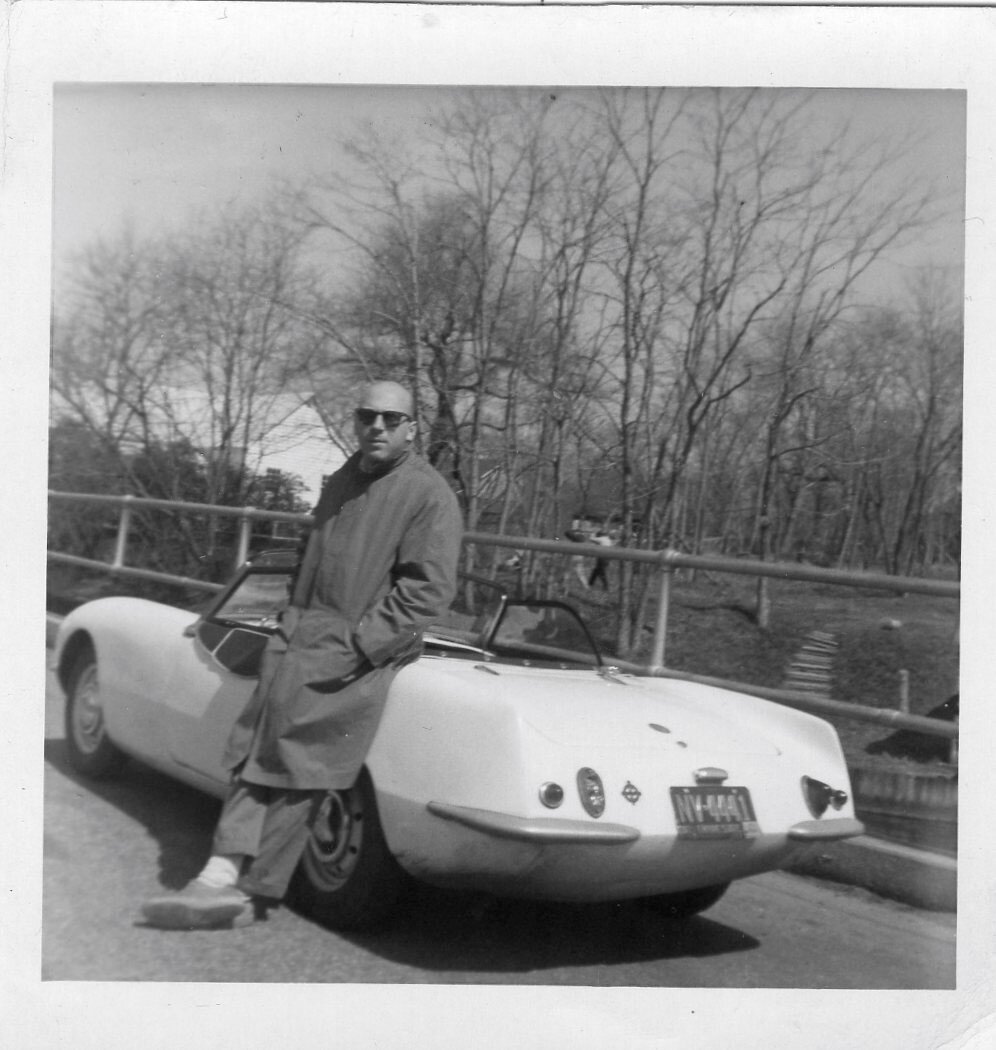

6) Boy with toy (my Elva Courier) near Lime Rock, Connecticut (1962). Drove this in a few gymkhanas, but my favorite was to take the car out late at night and drive around the inner roadway of Central Park, listening to the heavy rumble of the engine echo off the stone outcroppings and the walls of the big apartment buildings along Fifth and Central Park West.

7) The Novi Vinodolski, Yugoslav freighter that took me to Europe and a year and a half in Spain where I began to write and publish (1965-6).

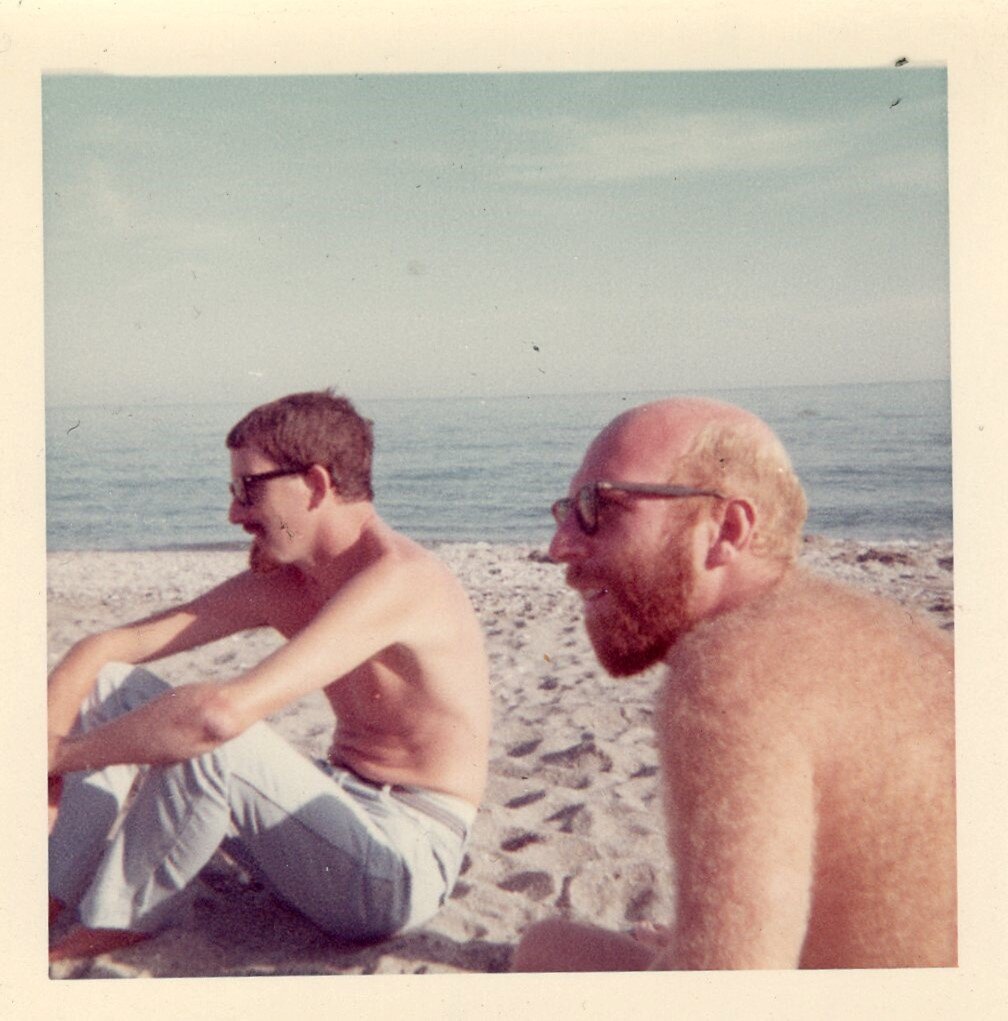

8) On Burriana Beach, Nerja, Spain with Irish novelist, Aidan Higgins, who introduced me to major European writers, at that time little known in America: Benjamin, Musil, Broch, Canetti, among my deepest lifetime readings and rereadings. In the 60s, it was a sleepy fishing village with only a handful of estranjeros living there. Today it is one of the overbuilt horrors of the Costa del Sol.

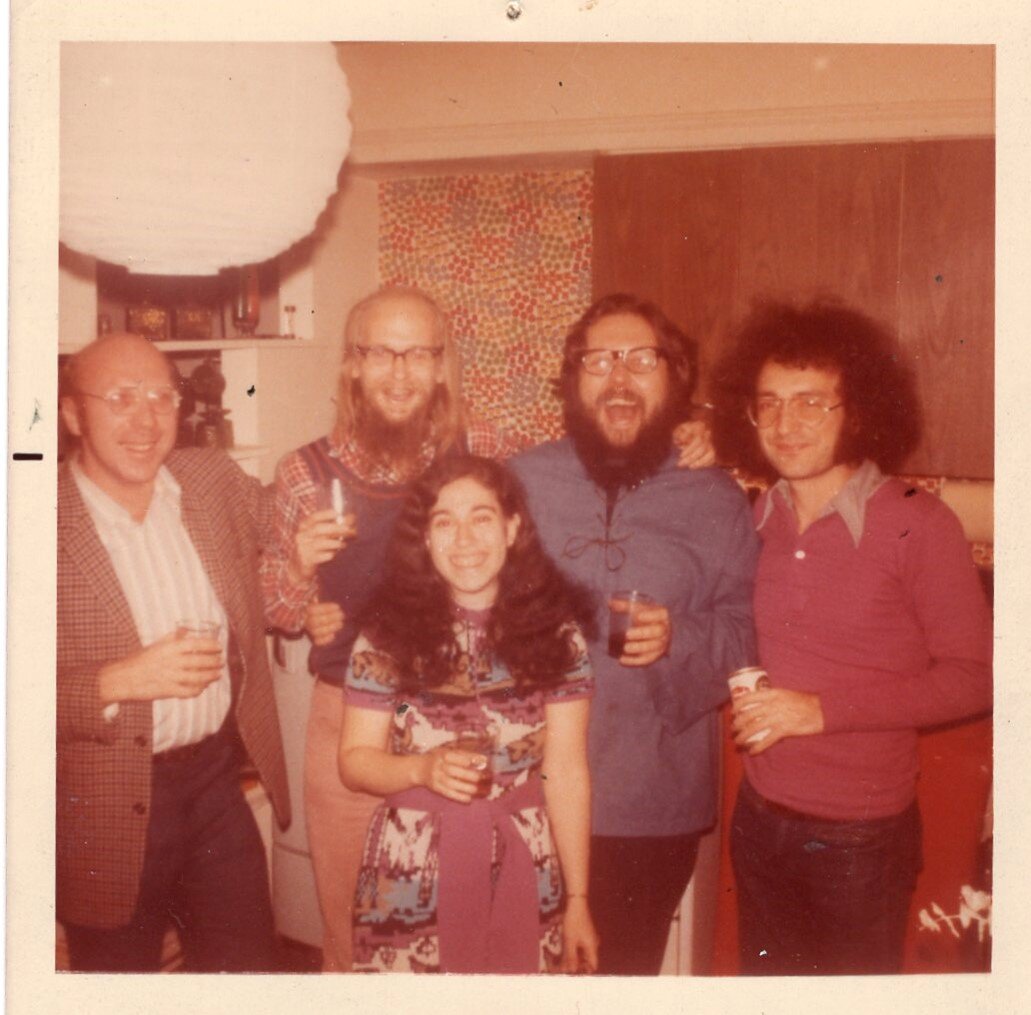

9) Poet pals, left to right: me, Nathan Whiting, Rochelle Ratner, Charles Levendosky, Hugh Seidman. In Rochelle’s apartment on Spring Street, 1967. Hugh and I (and I think Nathan) are still standing.

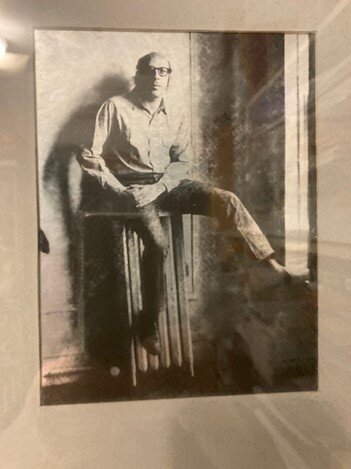

10) Portrait by the photographer and friend Michael Martone, 1971, taken in my apartment on East 15th Street. The head portion used as the author’s photo for my first full-length collection, Accidental Center (1972).

11) In front of George and Mary Oppen’s doorway on Polk Street, San Francisco. George had died a few years before, and I was staying at Mary’s house in Albany, California.

12) Rainbow picture taken from the deck of our cabin at 8800 ft. above Westcliffe, Colorado where we have summered for nearly fifty years. Until recent drought times, there was at least one rainbow almost every afternoon. Westcliffe is one of only a few dozen places in the world with a “Dark Skies” designation, and at night, the constellations and the thick swath of the Milky Way seem almost within arm’s reach. Two of my books and at least three of my poems have “constellation” in their titles.

13) Fisherman’s Wharf. San Francisco, 2003. With Carl Rakosi at his 100th birthday party.

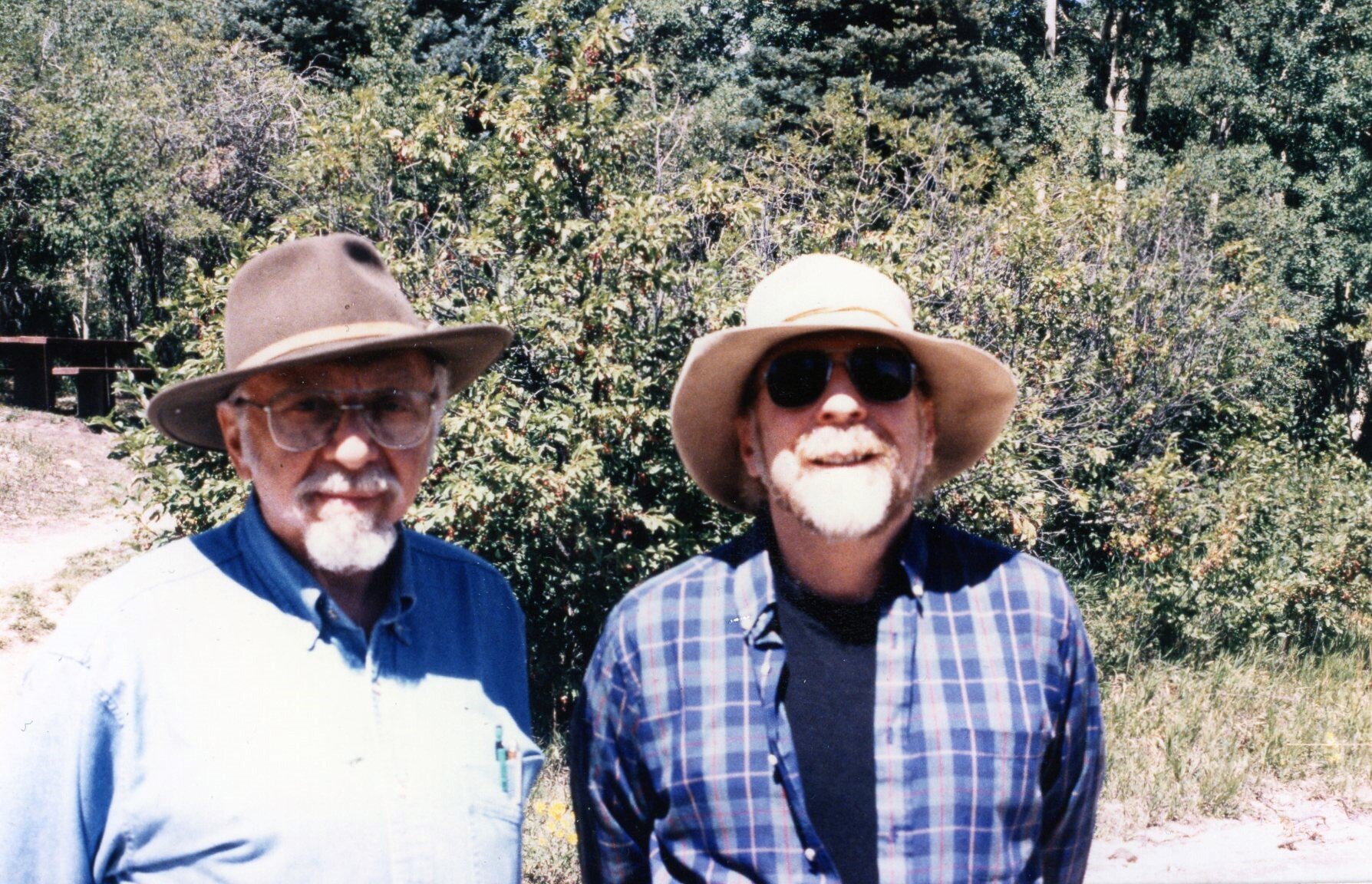

14) With my late friend Armand Schwerner on the Venable Creek Trail in the Sangre de Cristo mountains above our cabins in Westcliffe, Colorado (mid 80s).

15) Sitting on a bench at the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida (2015).

16) With Jane at Third Blue Door in the 10th arrondissement surrounded by French artists, actors and intellectuals (2016).

17) Signifying tile mosaic at an old noble mansion in Lisbon (2017). Our good friend the painter Paula Rego was commissioned to add a mosaic to the collection, but I cannot find a picture of it.

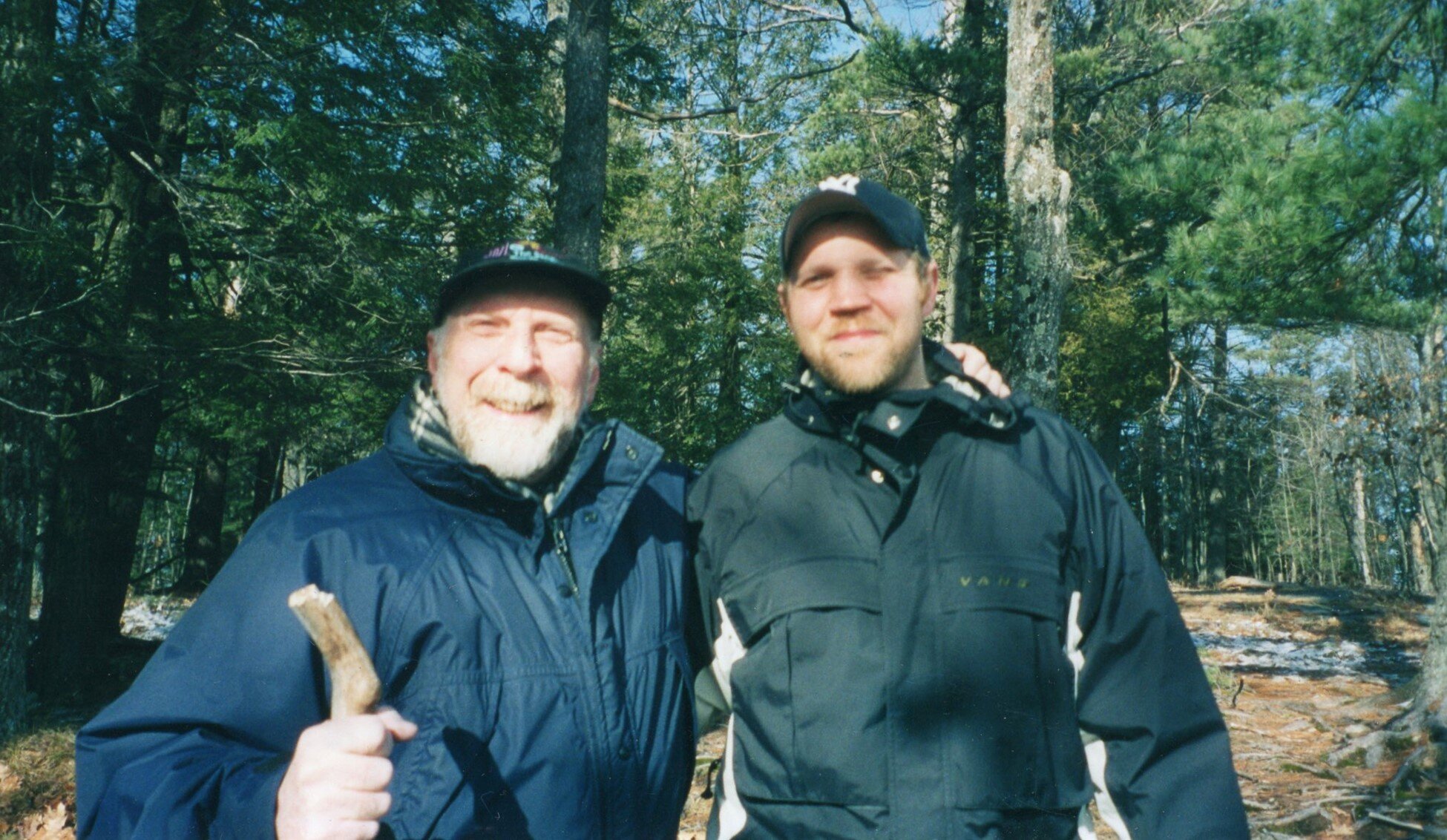

18) With my son Nick hiking the Severance Mountain trail in Adirondack State Park near Paradox Lake. Every poet’s address, the lake gains its name from periods when heavy rains or snow melt cause water to flow backwards out of the lake into the streams and creeks that usually feed it. The locals refer to this phenomenon as “paradoxing.”

19) Mets game with Nick. We’re smiling, but the Mets lost.

20) At the Met. We have been season subscribers for 25 years, so have probably seen at least 200 operas there.

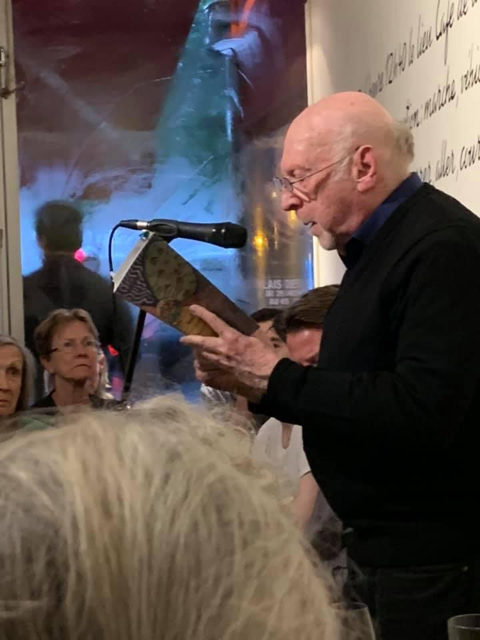

21) Last visit to Paris before the virus set in. Reading at Café de la Mairie (2019). Georges Perec sat at a window on the second floor of this café and wrote Tentative d'épuisement d'un lieu parisien (An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris). That’s Cole Swenson looking on.

22) New Year’s Eve, Dec. 31, 2020. Our 18th Street apartment living room. Drinks and delicacies in excess trying to get ourselves out of the pain of not being able to share our time and our good fortune with friends.

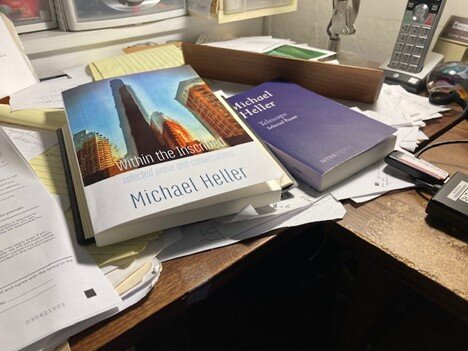

23) Most recent books bracketing the pandemic, Telescope: Selected Poems (2019) and a new collection of essays, Within the Inscribed (2021), with a cover photo by my son Nick.