Poetry: James Chapson

Introduction: On Jim Chapson

by Paul Vogel

If the poet Jim Chapson were no longer living, he’d surely be a prime candidate for the “Neglectorinos” feature here at Caesura. Not that his obscure status among the cognoscenti seems to have ever bothered him that much. Throughout his poetic life, in fact, Chapson has dismissed the callings of literary “success” with a decorous contempt.

Kent Johnson’s feature on Dispatches From the Poetry Wars, a notable exception to this neglect, provides an excellent account of the Chapson/Liddy circle in Milwaukee during the 1970s and 80s — all before my time. But as a friend of Jim’s for over a decade, perhaps I can offer some words by way of introduction, though I doubt anyone could do better than Kent’s epigram:

He is our Cavafy, completely unknown. Out of time. All of these things are exceptionally old — the sketch, and the tavern, and the darkening afternoon.

What does it mean to be unknown in the 21st century, when the global economy seems predicated on miniscule attention spans and the absolute commodification of desire? Today, even the young feel culturally irrelevant, connected, and neglected all at once. At least that’s what I gather from emo-rap. Perhaps because poets are conscious of their irrelevance, and because they deal with language and ideas, they express their isolation inversely as a kind of hyper-sociability. And because poetry nowadays is so very hyper-social and networked, we sometimes forget the solitary joys of going to a nice, quiet, air-conditioned library, finding a short book by an intelligent dead person, reading said book, feeling a tingle, then writing a short poem. This is a sequence I just imagined to contrast with how I actually spend my time, hunched over a laptop or scrolling through Facebook on my phone.

It’s also how I imagine poetry works for Jim, who, based on our infrequent “craft talks,” seems fairly habitual and unconnected in his practice. I mean that in the best sense of the word. He reads something or experiences something unusual, thinks about it for a while, and, if he’s not too sleepy, writes a short poem. The next morning, he edits. It’s a kind of minimalism, a methodical elegance reflected in the poems themselves. At the same time, they can seem to mock the reader with an air of nobility and privilege, as if to say “see how easy it is?” But really that’s just Jim, an old-fashioned bohemian intellectual: gay, sophisticated, reading from stacks of books, listening to classical music, going to Mass, not owning a car, etc. I could go on, but I risk caricaturing someone who is completely real and human.

The poems themselves are not “difficult” in the sense of formal complexity. There is no grand conceptual framework that must be understood, no radical play of signs. Ron Silliman came up with the term School of Quietude to describe a kind of neophobic poetry which, on the surface, might apply to Jim’s work; it is unassuming in the context of 20th century modernism. The typical Chapson poem consists of a few short stanzas and uses relatively normative, if somewhat literary, syntax. However, to read his poems as an example of quietude would be to gloss over their indebtedness to the New American tradition (especially Jack Spicer and John Wieners), Objectivism (especially Lorine Neidecker and Charles Reznikoff), and the whole tradition of English Enlightenment satire that most characterizes his work. The more “quietist” comparisons the poems invite to, say, Jane Kenyon, Philip Levine, or Jack Gilbert, are mostly superficial. These poets may employ elegant lines and an epiphanic form, but they do something different. For Jim, these elements are more often a springboard for satire, allowing for subtle turns that might otherwise be lost in a clutter of formal excess. They are understated — or unassuming, if you like. Kent is spot-on when he refers to the “pellucid diction and sardonic cool of the old Chinese, Greeks, and Romans.” I would add that a normative, direct address form operates here as a constraint, allowing the poems to achieve what Allen Grossman would call “one kind of success at the limits of the autonomy of the will to effect its purposes by other means.” That is, they use artifice to imagine themselves into being.

One notices this type of diction in the work of several San Francisco Renaissance poets. I will just point to one, George Stanley, who maintains a correspondence with Jim going back at least fifty years. Through Stanley, Chapson is one of the last living members of those who can claim a direct lineage with the Spicer circle. Neither Jim nor his partner, James Liddy, ever knew Spicer, but through their association with White Rabbit Press and friendship with Graham Mackintosh, they absorbed his influence.

I should add that Jim is funny, on the page and in-person; not in the way a crowd-pleasing comedian is funny, but as a kind of anti-humor, dark — well over 77%. There are elements of camp, but mostly it is bleak, unapologetic, Kafkaesque. That said, central to the work is a self-righteous (which is just to say deeply felt), countercultural and leftist-Catholic politics, one more informed by the Desert Fathers than by liberation theology. For that reason, his poems are accessible while offering something that is genuinely “other,” a rare feat.

And so, for all you neglectorinos out there in poetryland, I present Jim Chapson.

Out of Key With His Time:

A Note on F Holland Day

F Holland Day by Reginald W. Craigie, 1901

F (Fred) Holland Day was born in 1864 into a well-to-do Boston family which spared him the indignity of “making a living.” At the age of twenty he formed with Herbert Copeland a publishing firm, Copeland and Day, which published, always at a loss, nearly one hundred titles, including American editions of The Yellow Book (with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley), and Oscar Wilde’s Salome, along with works by Lionel Johnson, Stephen Crane, Robert Louis Stevenson, and others.

Taking up photography in 1886, Day joined Alfred Stieglitz in demanding that photography be recognized as a fine art, equal in status to painting. Stieglitz, however, soon came to view Day as a competitor and adversary. He derided Day’s work featured in an exhibition at the Royal Photographic Society in London in 1900 as representing an outdated pictorialism, now superseded by Stieglitz’s own modernist aesthetic. Stieglitz won out, aided perhaps by his aggressive tactics, and Day’s influence began to wane.

A complicating factor was Day’s choice of photographic subjects: male nudes in the guise of classical Greek and Roman antiquity, and in Christian iconography. Oscar Wilde’s 1895 trial and conviction for “gross indecency” cast Day’s classical-themed photographs into a new and troubling context. And while Christ and Christian saints had been portrayed in near-nudity for centuries, Day’s photographs of himself as a naked, crucified Christ made the protestant bourgeoisie more than a little uneasy.

Even today, it’s difficult to categorize Day’s photographs. Are they homoerotica? Camp? Blasphemy? And while in the fields of queer theory a thousand essays bloom decoding Day’s images, the photographs retain something undefinable and ultimately mysterious: an intense, inchoate longing which his art could never satisfy.

What I find sympathetic in Day is his stance at the nexus of classical Greek and Christian philosophy, specifically the overlap between the Song of Songs (ur-text of Christian mysticism), and Plato’s Phaedrus. I admire the obsessive quality of Day’s art (in 1898 he made over 200 negatives of himself as the crucified Christ), and the wordless, self-consuming desire manifest in the photographs.

Day abandoned photography in 1915. Some say it was because after WWI he could no longer obtain the platinum required for his platinum-process prints, but perhaps he had held too closely and for too long a self-destructive desire for the Other. In any case, by 1917 Day had retired to the family mansion, increasingly reclusive, looked after by servants. He died in 1933, his fame as an artist long forgotten.

— James Chapson

Atlantis

The people of Atlantis didn’t panic

when their island sank beneath the sea.

They found to their surprise

they could breathe quite easily.

Waves passed overhead like clouds;

sunlight filtered down as it always had

over the formal gardens, the stately colonnades.

A powerful, prosperous nation,

Atlantis had become arrogant;

the inundation, Plato says,

came as a punishment from Zeus.

The Atlanteans accepted this.

It was more peaceful now:

everyone moved more slowly;

little fish swam right into their mouths.

Relieved of conquest, they turned again

to the pursuit of the good;

and themselves spread the rumors believed everywhere

that Atlantis had been destroyed.

FH Day and Maynard White in Sailor Suits, self-portrait, 1911.

Bishop Fisher’s Tippet

When the lieutenant entered Fisher’s cell

to tell the bishop it would soon be time

for his beheading,

Fisher asked to take a nap,

for he had not slept well that night

owing to illness.

Later when he woke and dressed

he asked for his furred tippet,

to protect his health against the cold

in the last half-hour of his life.

And when the bishop’s head

was placed on London Bridge

it seemed to speak.

No record’s left

of what it said, but at the end

this was John Fisher’s message:

Pity, mercy, equity and justice

have no honour in the counsels of a king;

when you are weary take a nap—

you’ll feel better for it;

and a furred tippet on a cold morning

is a great comfort.

So the executioner

threw the head into the river

and replaced it with the head of Thomas More.

But that head, too,

brought the king no peace.

The Seven Last Words of Christ (Woman Behold Thy Son, Son Thy Mother), 1898

Styli

In the year 877, students of the Irish

philosopher John Scottus Eriugena,

angered by his baffling paradoxes,

attacked him with sharpened styli,

stabbing him repeatedly;

but the wounds, though many, were shallow

due to the weakness of the boys’ arms,

rendering the philosopher’s dying

painfully long drawn out

according to William of Malmesbury,

writing three centuries later

and likely conflating the philosopher’s death

with the martyrdom of Cassian of Imola in 363

as recounted in the Roman Martyrology;

so it might be prudent to doubt the story’s

historicity, but not its truth:

a story so compelling must be also true,

even if unsupported by the facts;

all the more so if unsupported by the facts.

St. Sebastian, 1906

Five Utilitarian Propositions

It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied.

—JS Mill

It is better to be a lap dancer dissatisfied than a senator satisfied.

It is better to be a meadow dissatisfied than a minefield satisfied.

It is better to be a fœtus dissatisfied than a condom satisfied.

It is better to be a pornstar dissatisfied than a writer of young adult fiction satisfied.

It is better to be a cloud dissatisfied than a mountain satisfied.

The Last Prophecy of Nostradamus

A gay president will re-name the White House

the Rainbow House, and paint it accordingly;

then great storms will arise, tornadoes scour the land,

the sun burn hotter than before, great glaciers fall into the sea;

monkeys will bring a terrible plague,

purple blotches appearing on the skin of the sick

who will kill themselves rather than succumb to madness;

airliners will mate with office towers,

giving birth to destruction and death;

children will turn fire sticks upon children,

killing them in vast numbers;

those seeking refuge in cinemas will likewise be slaughtered;

the one percent will scorn the ninety-nine percent,

and the fifty-three percent despise the forty-seven percent.

In the last days, Rationalists will proclaim themselves wise

expounding a threadbare positivism;

at this, the Cosmos will sicken, vomit them out

into their self-created emptiness, and the Great Healing begin:

men and women will call each other brother and sister, and

Hello Kitty lie down with My Little Pony

ushering in a thousand years of peace.

Rattle

From cliffs above the stony beach

could still be heard the rattle

of Matthew Arnold’s melancholy pebbles.

Orpheus, 1907

Café Odeon

The professor was at his usual table,

an espresso before him,

his attention divided between

the Neue Zürcher Zeitung and passersby

hurrying to commerce or romance.

And so he sat, the espresso long cold,

until, following complaints, the management

covered him with a glass case,

for there was now an odor of decay.

Passing schoolboys dared each other

to look in the window

at “The Professor in the Vitrine”

who was said to appear as a flaming

beard in the dreams of those who did.

At last, one year when the floor

was being retiled, the Professor

was removed to the basement

where he remains in his glass case

beside a mouldering parrot, which once,

bright from the forests of Brazil, perched

noisily upon the shoulder of the café

owner’s wife, herself long dead now.

Portrtait of F Holland Day, by Alvin Langdon Coburn, 1900

The Viennese Café

The Viennese café imagined

is more elegant than any actual café.

I prepare for bed as for a journey

to a land where the dead are alive.

The Seven Last Words of Christ, 1898

Julia Ostrowska

To prolong her life when she was dying of cancer,

Gurdjieff would daily give his wife,

Julia Ostrowska, a glass of water

which he’d held intently in his hands,

imbuing it with cosmic energies.

Then, taking the glass, before she drank it,

Julia Ostrowska with what remained

of her declining powers

would turn it back to ordinary water.

Song of the Epiphyte

We find support from other plants

but we don’t live off them.

In temperate zones the lichen,

the quiet moss; in the tropics orchids

and the staghorn fern adopt our rule.

Among rooted plants

we witness to the transitory

living our whole lives out on a limb,

on whatever the wind brings.

Wind

It wouldn’t be bad being like the wind,

stirring things up, settling things down,

going nowhere, circling around.

The wind can’t want to be anything

other than what it is

because it’s hardly anything at all:

a tree bends, a newspaper flies by,

a coolness enters the day; “it’s the wind,”

we say.

Everywhere it’s different,

but it’s really always the same,

whether it’s whipping up flames somewhere

or bringing us buckets of rain.

It blows wherever it will

indifferent to praise or blame.

The Entombment, 1898

Mooncakes

1

One night they took us to a dormitory’s

flat roof, gave us cups of sweet wine,

and mooncakes filled with bean paste.

It was cloudy, cold; we couldn’t leave

until the moon showed up.

2

Another time they took us to a lake

for a picnic. In a clearing in the pines

we came across a group of young

factory workers dancing to a boombox.

3

Once they took us to a model village

where the cooking gas came through tubes

from a communal septic tank.

With the local officials we got drunk under

flyblown portraits of Stalin, Marx, and Engels.

4

One morning they took us unexpectedly

on a picnic. Passing the Public Security Bureau

we saw a crowd gathered around two men

roped together, placards hanging from their necks,

on the back of a flatbed truck

5

When they took us to a secluded beach

where, they said, the late chairman walked

on his visits to Dalian,

we looked down as if to see

next to ours his footprints in the sand.

St. Sebastian, 1906

The Temple

Out of hospitality, and to remove us

from the city on the day of

public executions, our hosts arranged

an outing in the country.

From the parking lot a path crossing a field

led to a glass and concrete pavilion

meant to resemble a traditional shrine,

where they served us tea as we admired

a jade-green river bearing sewage

between cultivated fields,

and no one said a word about the rubble

of carved stones lying among weeds,

all that remained of an ancient temple

recently destroyed in the Great Cleansing;

for if the time had passed to applaud

the temple’s destruction, the time

to deplore it had not yet come.

Two at the Cross, 1898

The mission

began when our yearning for transcendence

congealed to form an orbiter carrying

an instrument pod designed to explore

the surface of a mysterious planet,

and proceeded flawlessly until

at a critical phase the lander descended

too quickly, and the package of delicate

instruments exploded on the rocky surface,

leaving only a black smudge, and a small

white spot: the lander’s frail parachute

from which had hung our hopes.

Kahlil Gibran, 1897

The King

When the King speaks seated on his throne

his words are heard throughout the realm.

But there is no king, so he has no throne,

and he can be neither standing nor sitting.

There is no king, so he has no realm,

no words to speak, no subjects to hear him.

Yet from his throne the king is speaking,

his subjects hear, and there is no king.

The Vigil, 1898

Up Here

Having climbed a low hill above the village,

you look back and are astonished:

steep, snow-covered mountains

rise all around you.

Cattle graze the high pastures;

a few farm buildings cluster

beside a square, three-storied house

with small windows.

You see no one but a village girl

in a shop selling farm equipment

who knows little about the life up here,

yet somehow you understand

those in the square, yellow-plastered house

live quietly, speak seldom, have no interest

in the life below.

Now mountain shadows edging across fields

mean you must decide

whether to go back down to the village,

or ask at the silent house to stay

up here.

Crucifixion, 1898

Biology Lesson

The children believed

when they saw for themselves

what the teacher had promised:

the caterpillars’ brown coffins

breaking open; butterflies emerging,

unfurling their delicate wings.

But there were those that never opened.

They must have lacked some element

necessary for the transformation,

the teacher said,

tossing them out of the terrarium

still clinging to their twigs.

Alvin Langdon Coburn, c. 1900

Three Intimations of Mortality

The ROTC first aid film

featured gurgling bullet wounds.

*

In the autopsy room,

the hospital volunteer saw

piled on something like a breakfast tray

the cadaver’s innards.

*

Right over there, just offshore,

your classmate Billy was killed by a shark.

Lago di Como

He was sitting on the café terrace

overlooking Lago di Como, two waiters

attending him, one bringing

the espresso doppio, the other

a chocolate biscuit on a white plate.

It was the end of summer; boys

of impossible beauty drifted by.

How could he not think of Aschenbach?

Triangular sails glided, ferryboats puffed

rhythmically. The waiters approached,

naked, but this didn’t seem unusual,

lifted and carried him to a waiting ferry.

He wept at their tenderness.

A dog barked, the boat began to move,

the waiters were gone, but the captain,

a boy in a loose white shirt, said,

“I will take care of you now,” speaking

without words, directly into his heart.

They neared a landing of veined marble

on which two candles flickered

from tall candlesticks. Little waves

splashed against the stone; there was

no one to meet him. “Don’t worry,”

the ferryman said, speaking again

into his heart, “everything is provided for.”

The Vision, 1899

Departure Lounge

Now you have entered the departure lounge

where you will wait with the others

for the announcement to proceed to the gate.

On the other side there will be a going out

and a return, and at the end, you have been assured,

someone to welcome you and take you in.

A SKÁLD’S GALLERY

James Chapson

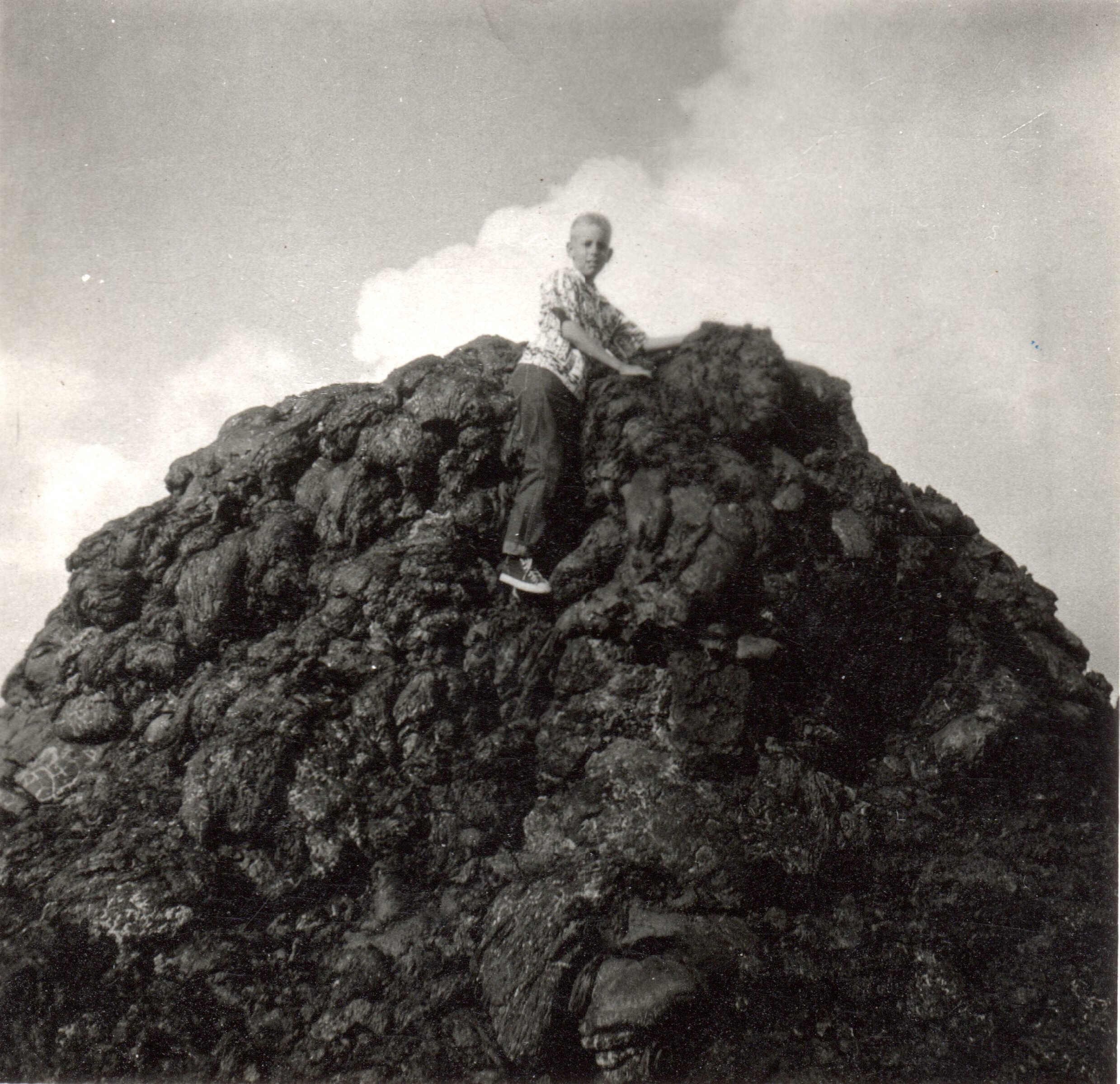

1. The journey begins, as all true journeys must, on horseback. Chapson Ranch, Pagosa Springs, Colorado, c. 1955.

2. He finds himself drawn to a spatter cone from whose vent issues sweet-smelling vapours. From deep within the earth comes an enchanting voice telling of all the adventures that await him, the adversaries he will confront and overcome, his final goal and whether he will attain it, and the date and manner of his death. But it speaks in the dactylic hexameters of Attic Greek, an embarrassing lacuna in his education; he understands not a word.

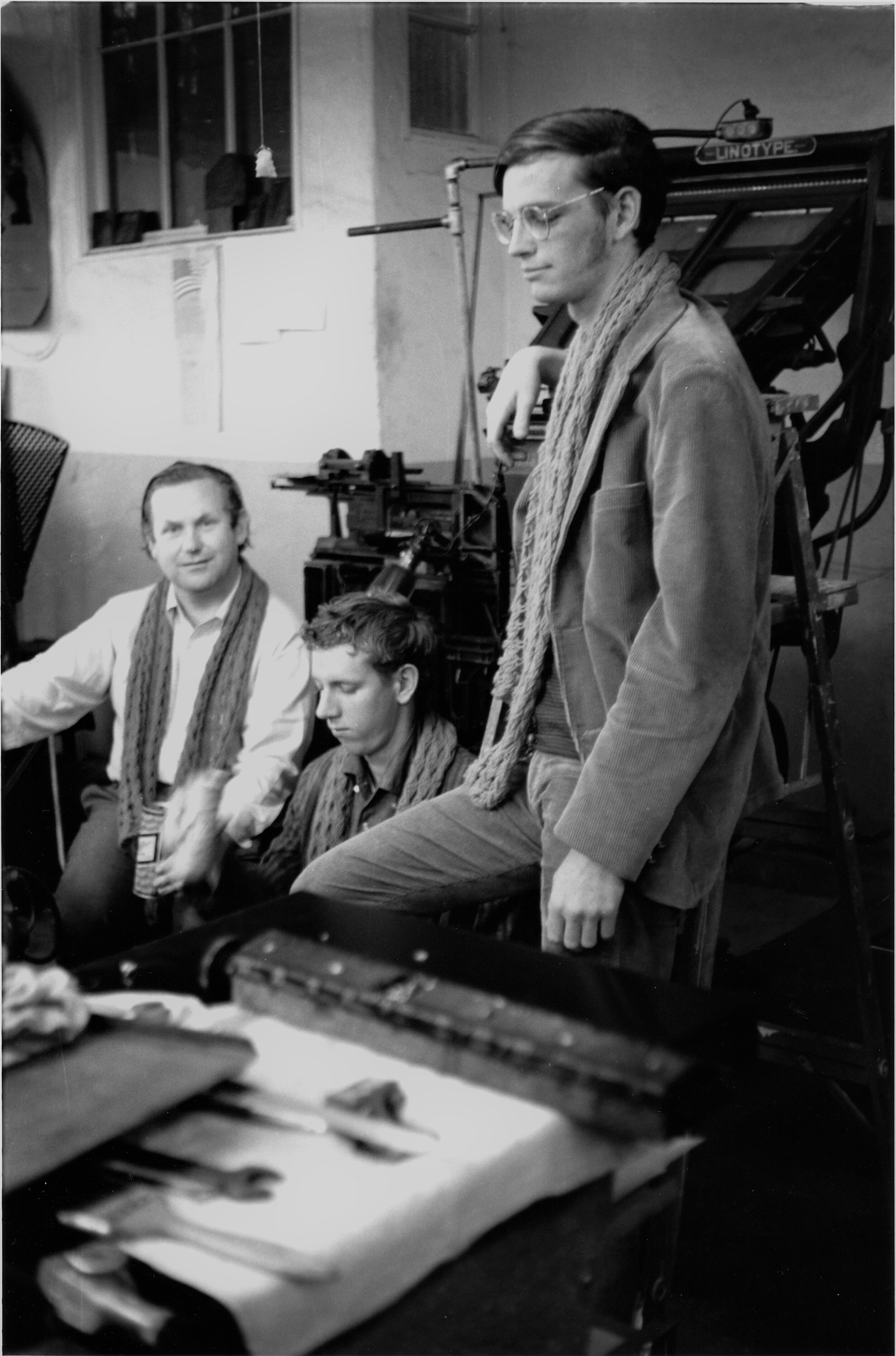

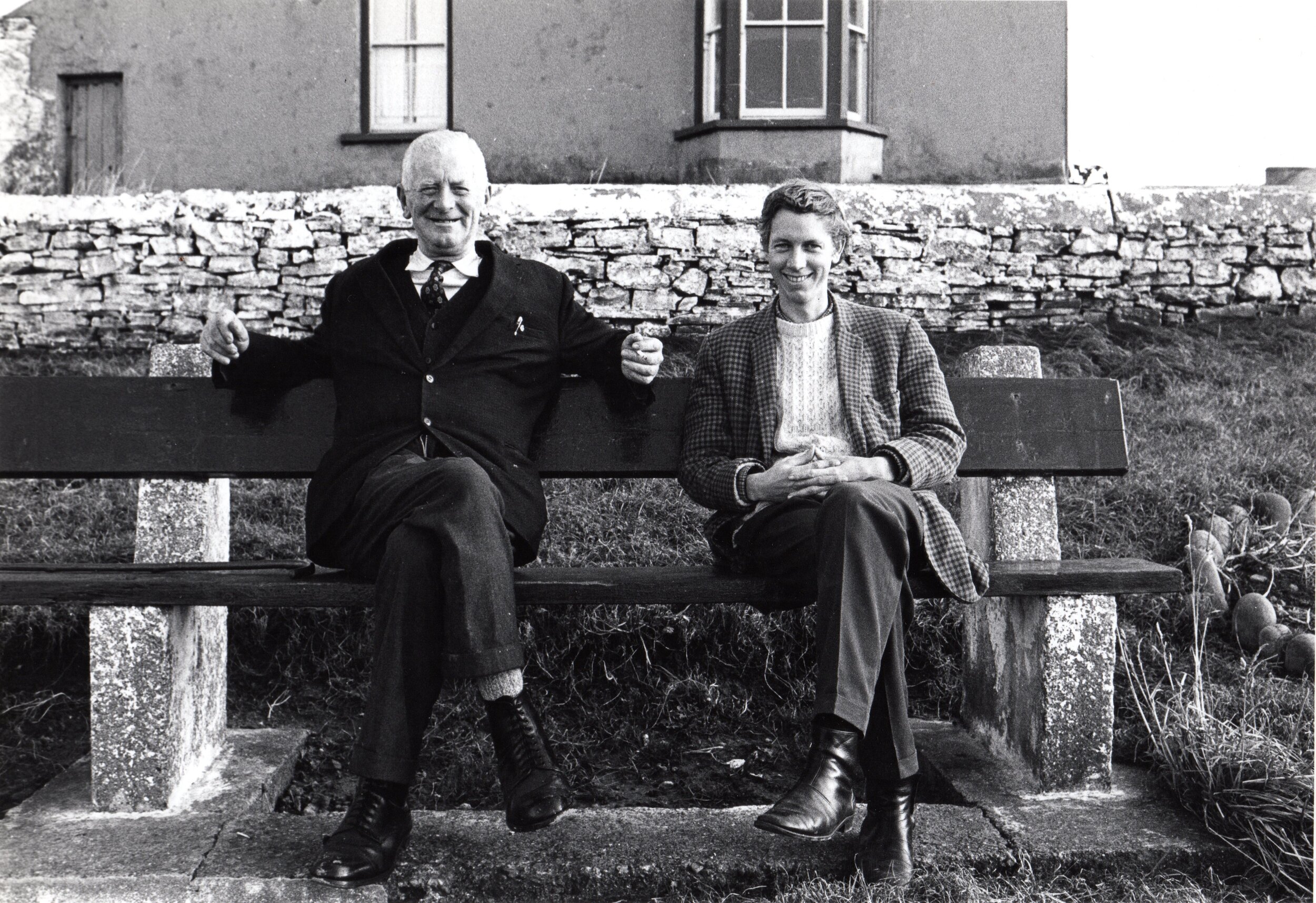

3. As if by magic, ten years pass and he finds himself at 574 Natoma St., S.F., in the cave of the Scottish druid G. Mackintosh. J. Liddy, J. Chapson, and T. Hill have been tasked with guarding the sacred Linotype while the druid is out gathering herbs for his powerful elixirs.

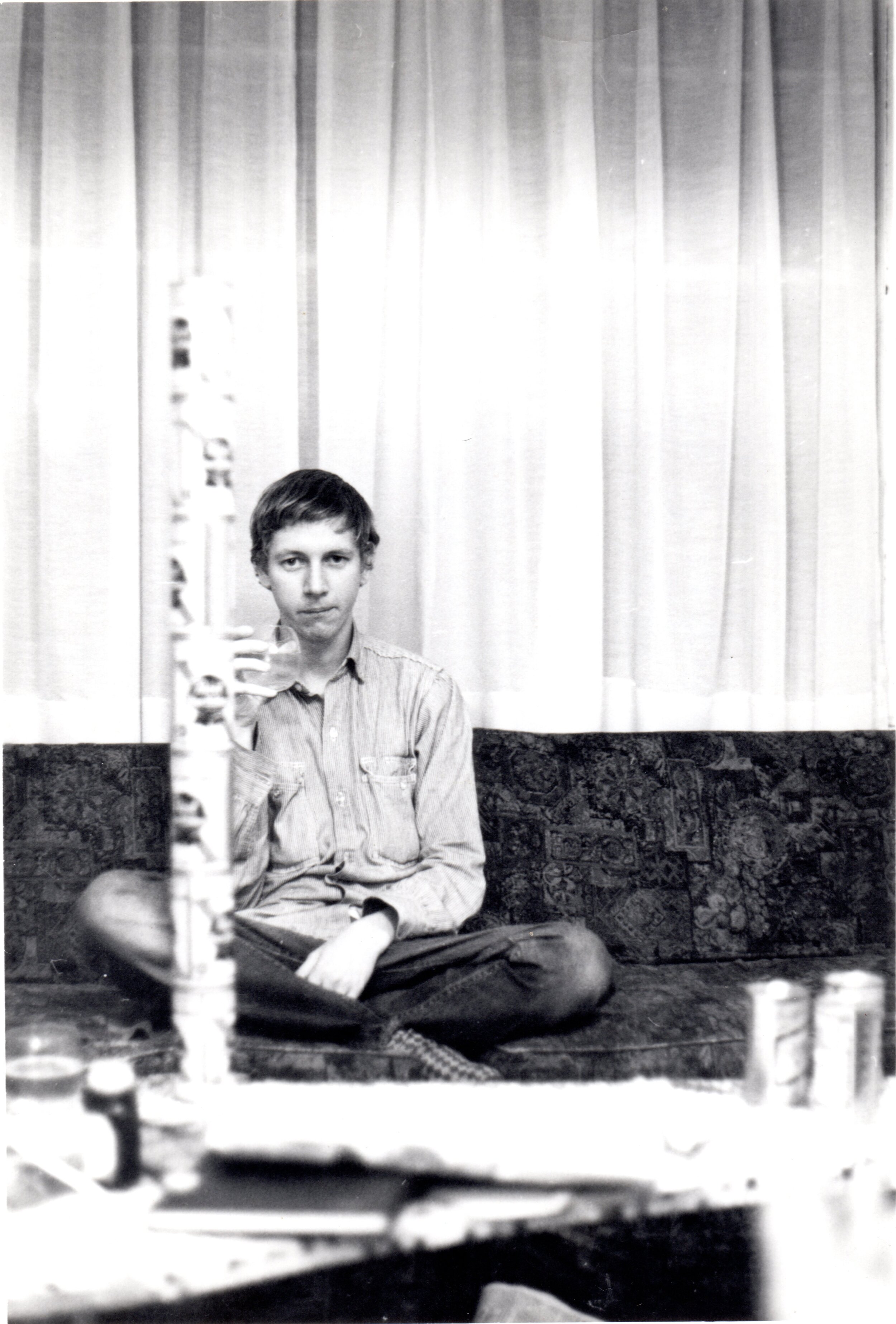

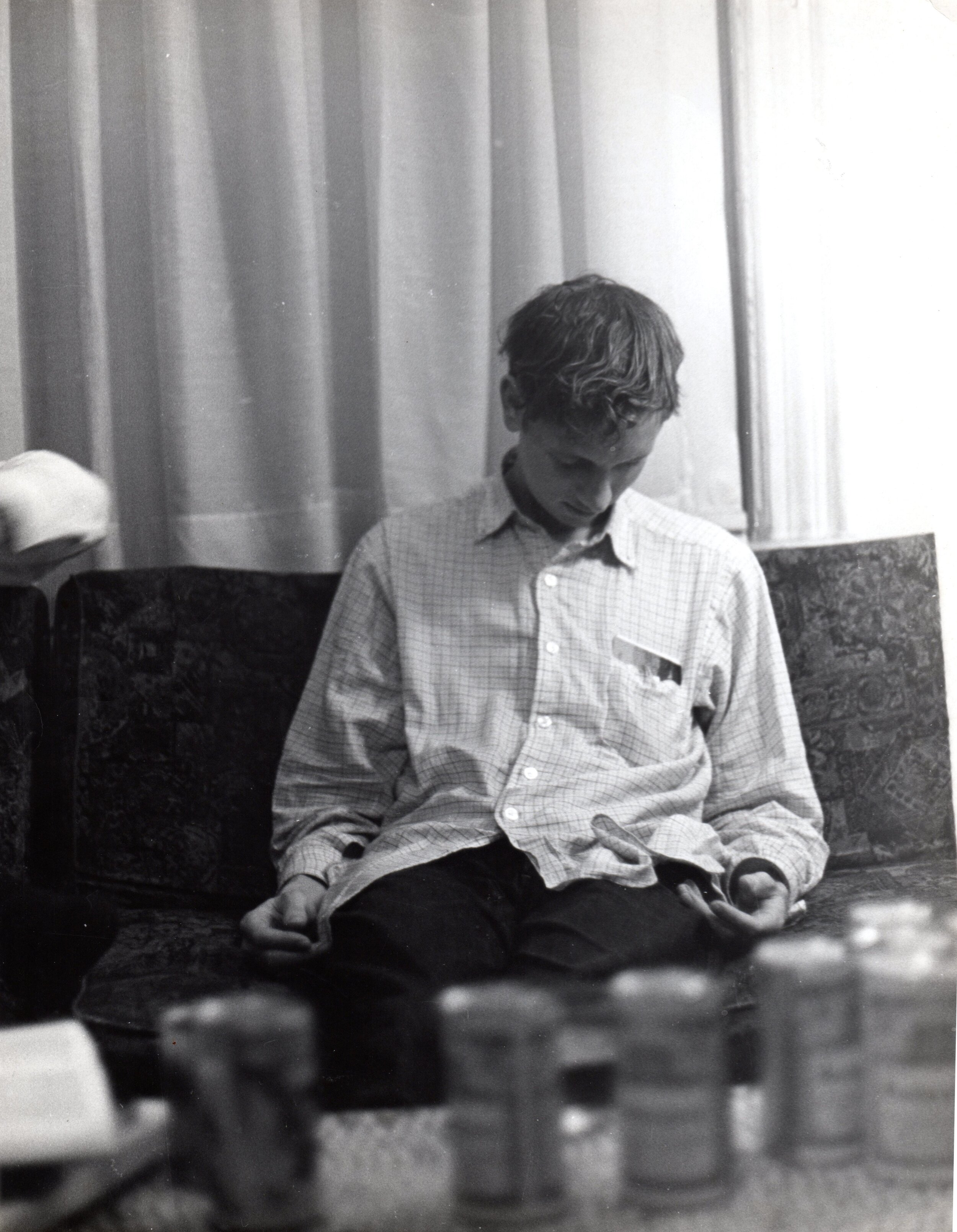

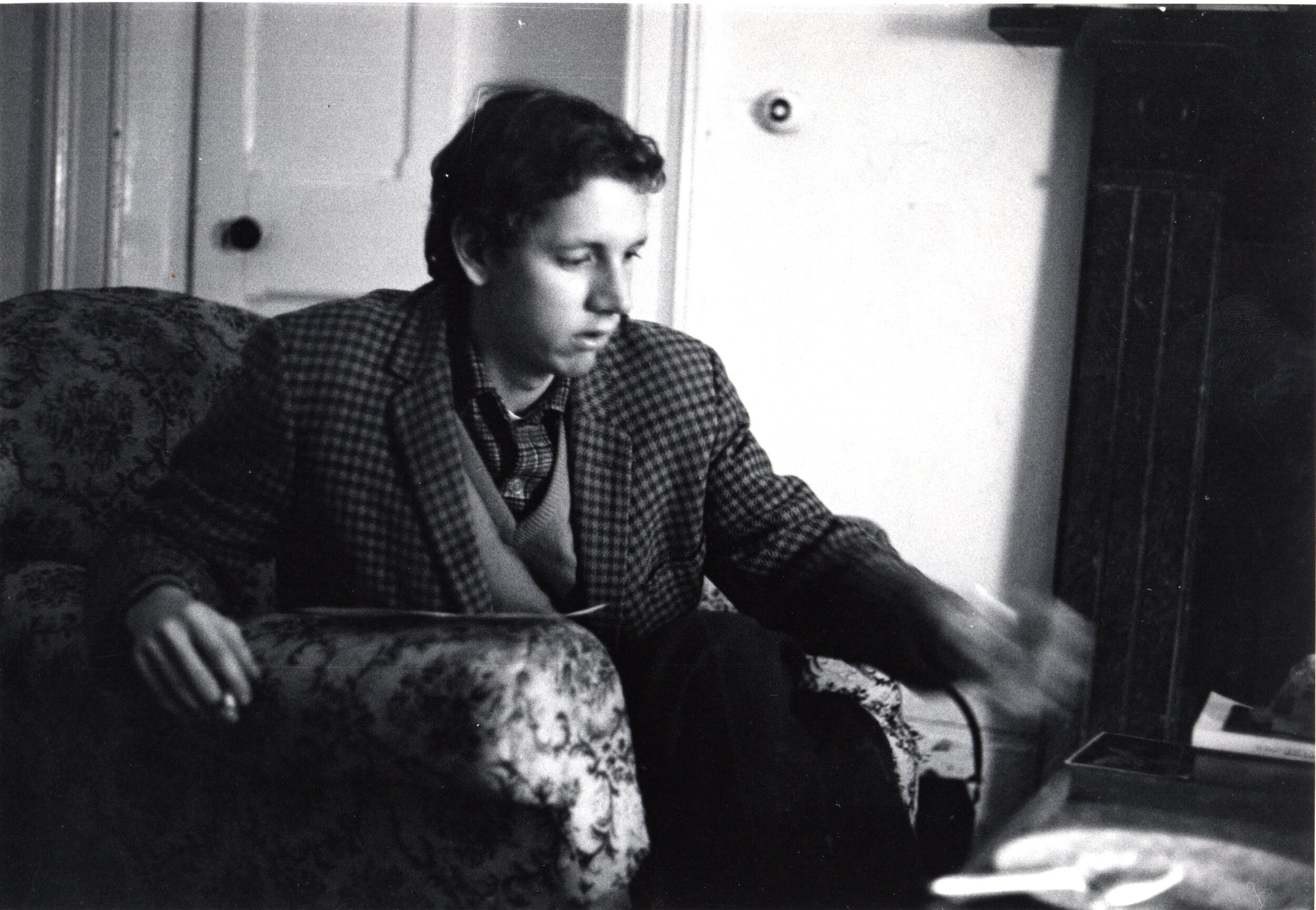

4. Brooklyn, c. 1969. In profound meditation, he has his first insight into his true nature. Initially perplexed, he is soon . . .

5. . . .gate gate paragate parasamgate . . .

6. Transported to a Foreign Land, he is accepted as a postulant by G. Fitzpatrick, Master of Numbers, on condition that he clean the duck pond daily. The Master is shown here with the postulant, expounding on the notoriously treacherous number three.

7. From the piano, An tUasal Seórse Mac Giolla Phadraig, Master of Numbers, directs the weekly recital by the Cill Chaoi Pythagorean Céilí Orchestra. Stringless guitar, J. Chapson; banjo, M. Chambers; mandolin, G. Carmody; tin whistles, W. Siverly, J. Liddy, P. Keene, P. O’Donal; fiddle, F. O’Dooney.

8. After a long vigil, an evanescent something appears before him, diaphanous, shimmering. Reaching out, he seems to hold it for a moment in his hand before it disappears.

9. He has been assigned a bodyguard, the sturdy G. Clarke (pictured), formidable ninja-botanist. Why he needs a bodyguard will soon become apparent.

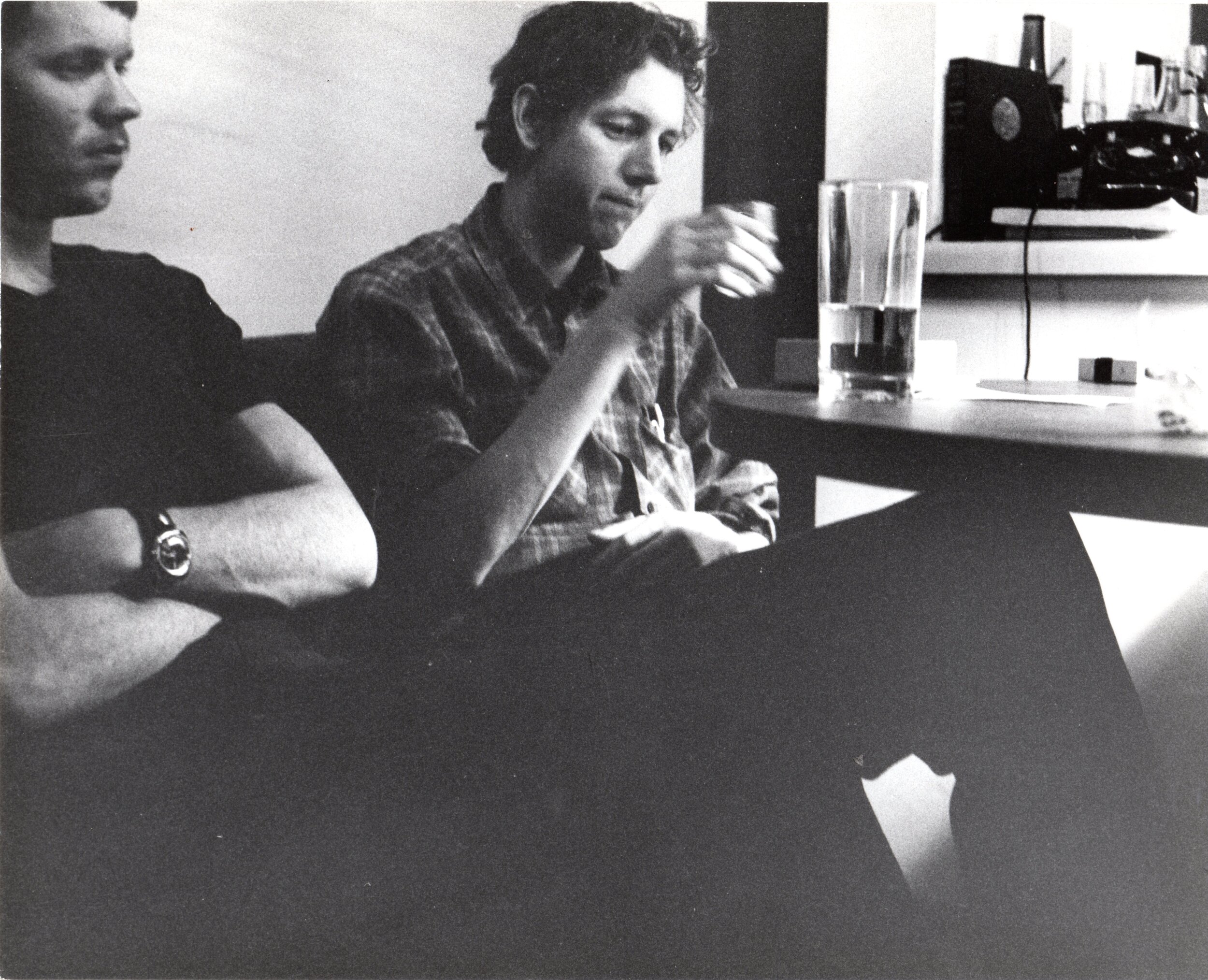

10. Symposium. Santa Monica, c. 1972. Subject: horse whispering. W. Reisner and J. Chapson prepare to explore the proposition, “It is ordained that all such that have taken the first steps on the celestial highway shall no more return to the dark pathways beneath the earth, but shall walk together in a life of shining bliss. . . .”

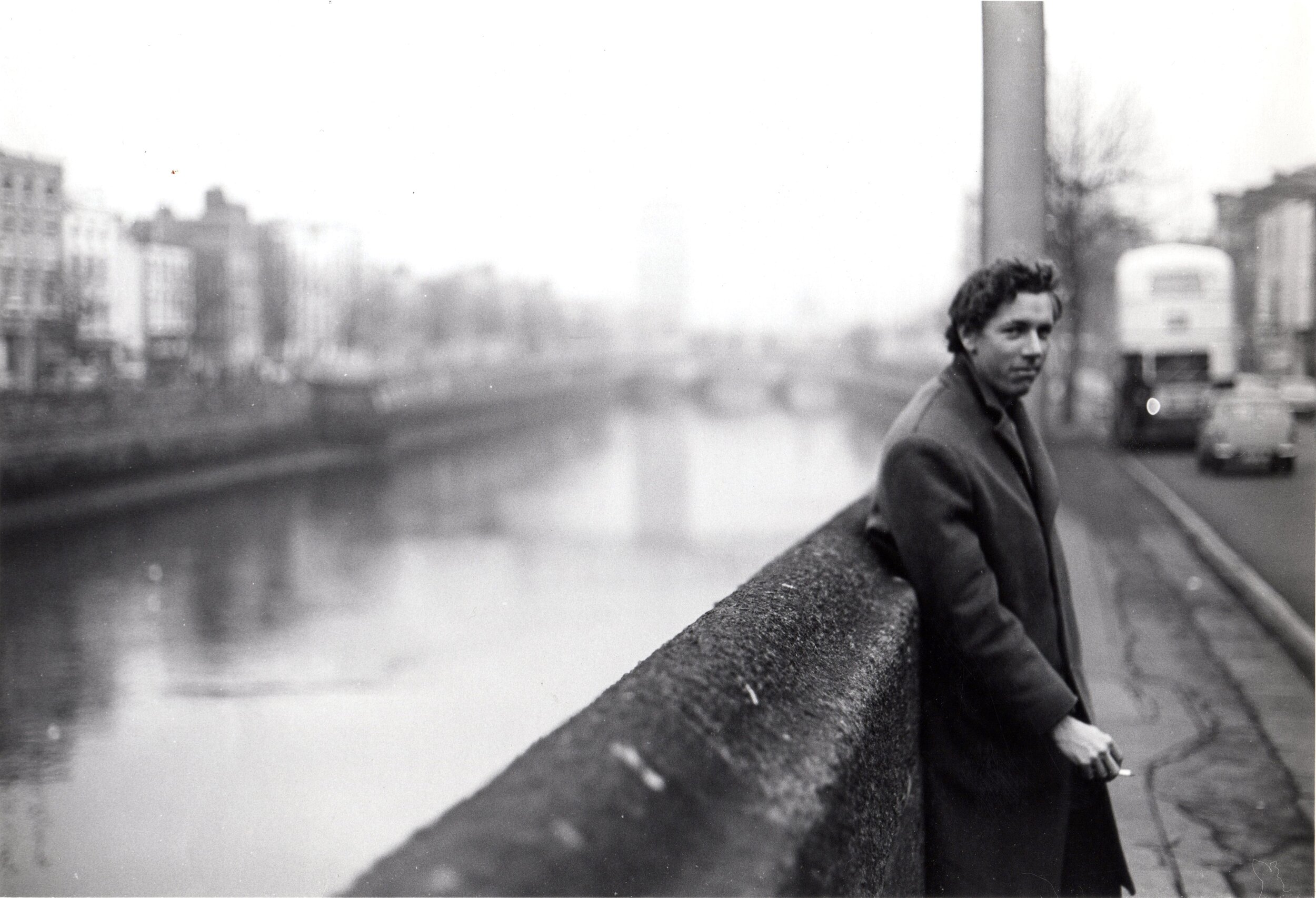

11. In a European capital, tempted by existentialism, he has turned his back on the river. Yes, that is a Gauloise.

12. Symposium. New Orleans, c. 1975. Participants: J. Liddy; R. Hand; V. Wren; J. Chapson; Faye; W.H. Schlau. Subject: Creatio ex nihilo.

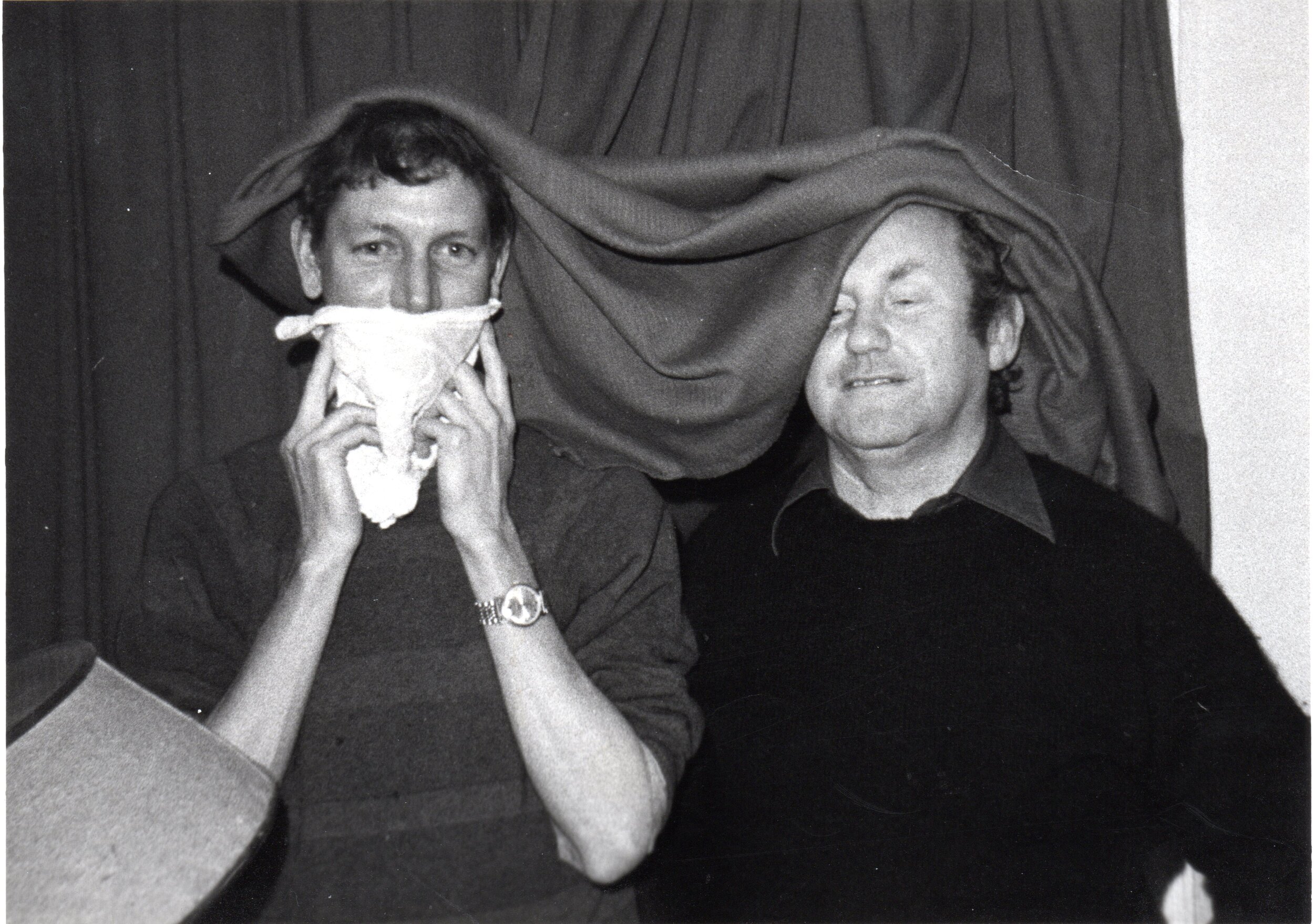

13. J. Chapson; J. Liddy. Milwaukee. It was sometimes necessary to adopt a disguise.

14. Symposium. Milwaukee, c. 1980. Participants: C. Nash, moderator; L. Briggs; J. Chapson; J. Liddy; Anonymous Peripatetic. Subject: Why is there something rather than nothing?

15. During the process of psychic integration, the initiate may undergo a series of humiliating metamorphoses, such as the one pictured here in a Milwaukee rectory, c. 1982.

16. Symposium. Axel’s. Subject: Is truth beauty, or is it the other way around? Panelists: W.H. Schlau; J. Pendragon; J. Liddy; J. Chapson.

17. Beside Nu’uanu stream, he consults a wise woman, intelligent, holy, unique, manifold, subtle, mobile, clear, unpolluted, distinct, invulnerable, loving the good, keen, irresistible, beneficent, humane, steadfast, sure, free from anxiety, all-powerful, overseeing all, and penetrating through all spirits that are intelligent, pure, and altogether subtle. Her counsel is relayed corporeally, through a sequence of plates of dim sum.

18. 1978. With J. Liddy and the Blessed Thaumaturge J. O’Brien. He is wearing a “tie,” one of the liturgical garments symbolic of initiation into the holy mysteries: he is now “tied” to the Incomprehensible. Not long after, mirabile dictu, the Bl. Thaumaturge is taken up into the One from a golf course in Florida.

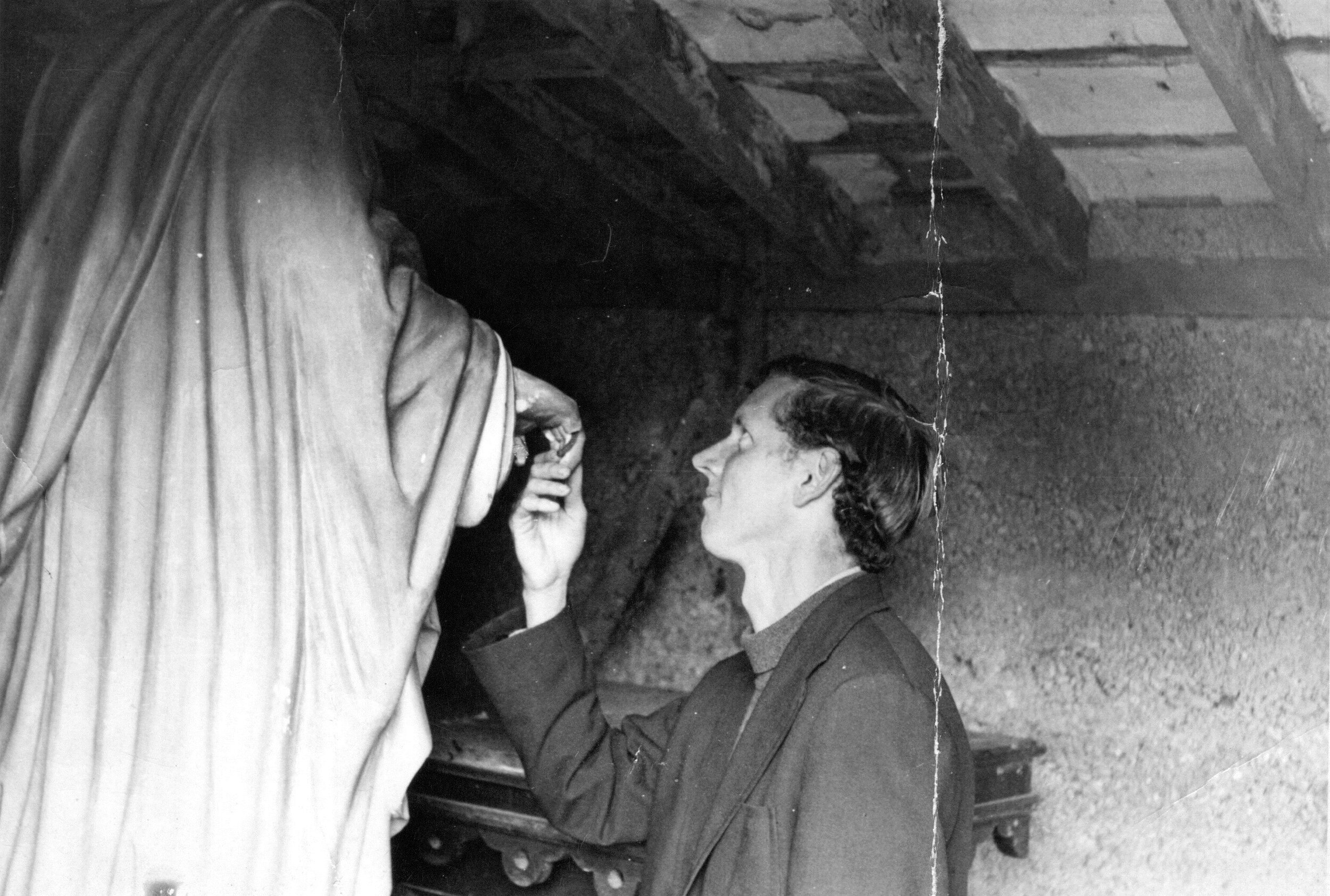

19. A Divine Personage extends a hand in welcome, sympathy, and understanding. Even though in the form of plaster, the proffered hand is an affirming gesture.

20. 2011. At last the Powerful Hand returns, now in the guise of flesh, its meaning clear: no more remains to be seen or said.