Commentary on Kent Johnson’s “Because of Poetry I Have a Really Big House”

Kent Johnson's edible (for some) or inedible (for others) poetics in Because of Poetry I Have a Really Big House addresses and offers a lingual escape hatch from a fascinating but plump paradox in the contemporary poetry scene: isn't poetry in North America both extremely creative as well as dreadfully goody-goody?

I'm not talking about the semiological guerilla warfare (a concept borrowed from Umberto Eco) of poets sporting large stacks of marginalized identities. That's a different beast altogether. About the latter, I wonder if they're writers or linguistic activists. I guess one can be both, however irritating that seems.

Here's what I mean:

The other day I asked a befriended poet belonging to the community of “untouchable” Dalits (about 300 million “untouchables” [achhoot in Hindi] live in a de facto apartheid system in India) what he would do if he woke up a Brahmin one morning. His answer, however unsurprising in hindsight, startled me: “going after Brahmin girls,” he said. In my opinion, this proves an interesting point: in the end, everyone wants to be a predator.

As a woman writer who’s published only in little magazines, this dilemma haunts me on a personal level: should I, for instance, mention in my bio that I was raised fatherless by an unemployed, divorced, and mentally ill mother? Should I mention that I’m not exactly heterosexual? Should I mention that my parents were Greek immigrants to Belgium used as human cattle or factory fodder? The thing is that I want my work to be appreciated for what it is and not because of (certain marginalized aspects of) my background. Due to current identity politics, however, not complying with the aggressive/compulsive imperative of “coming-out,” I’m sure my career as a writer will be slowed down (if it ever takes off at all). But I have no interest whatsoever to satisfy the fetishist desires of the mainstream. What does this all have to do with Kent’s book? I’ll try to illuminate:

Kent’s book challenges the desires of the mainstream. By doing this, he creates space for those (especially younger) poets Anne Waldman calls the “outriders”: writers who move along the academic poetry community but in a parallel way. There are few institutions offering a context for parallel poetic engagement. The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, Colorado is one. Lance Olsen, professor at Salt Lake City, also offers a home for experimentation. I’ve heard good things about Brown and Notre Dame. There are, however, more than two hundred MFA programs in the U.S.: that’s a lot of manicuring and canning of language.

I have no problem considering that for some of my fellow students it may have been enriching or formative, but to me the MFA experience was something akin to waterboarding. This isn’t a singular experience. There are other poets and writers out there who’ve lamented in private conversations the damage done by their respective academic programs. This touches upon the aforementioned paradox. There is so much literary creativity in America — marvelous and ingenious artists, writers and poets — but it seems that its energy is funneled or perhaps even strangulated in ways fitting the mindset of a male reader living in, let’s say, the Midwest (see Lance Olsen’s Architectures of Possibility: After Innovative Writing. He elaborates on this phenomenon). Kent’s Because of Poetry offers an exhaust and relief for the straitjacketing of the poetic imagination.

In my case, informal meetings and conversations with LA poet Will Alexander (an outrider poet and visual artist par excellence, I’d say) resuscitated my desire to write. Thank you, Will.

I had almost abandoned writing altogether.

Another befriended poet, who didn’t want his name mentioned here, asked me recently from where I earned my MFA. He said that my poetry was “wild.” He didn't know of any MFA program allowing this sort of “wild” imagination. This is telling. Whether he’s right or not isn't important. The academic manicuring of the imagination (and funneling to a particular kind of reader), on the other hand, is.

In my view, Because of Poetry decimates the inflated grandiosity of the poetry business and forces writers' feet back on the ground. I could talk about the satirical aspects of the collection, the wit, and delineate this or that stanza to prove my point, but others before me have already done that.

Reading Because of Poetry was an overall refreshing and humbling experience: language permitted to graze and forage instead of being confined to the feedlots of the mainstream academia — or worse, being canned.

That it is intelligently funny and dares to kick against the shins of the phallogocentric bastions of the poetry trade is a wonderful bonus. Merci, Kent!

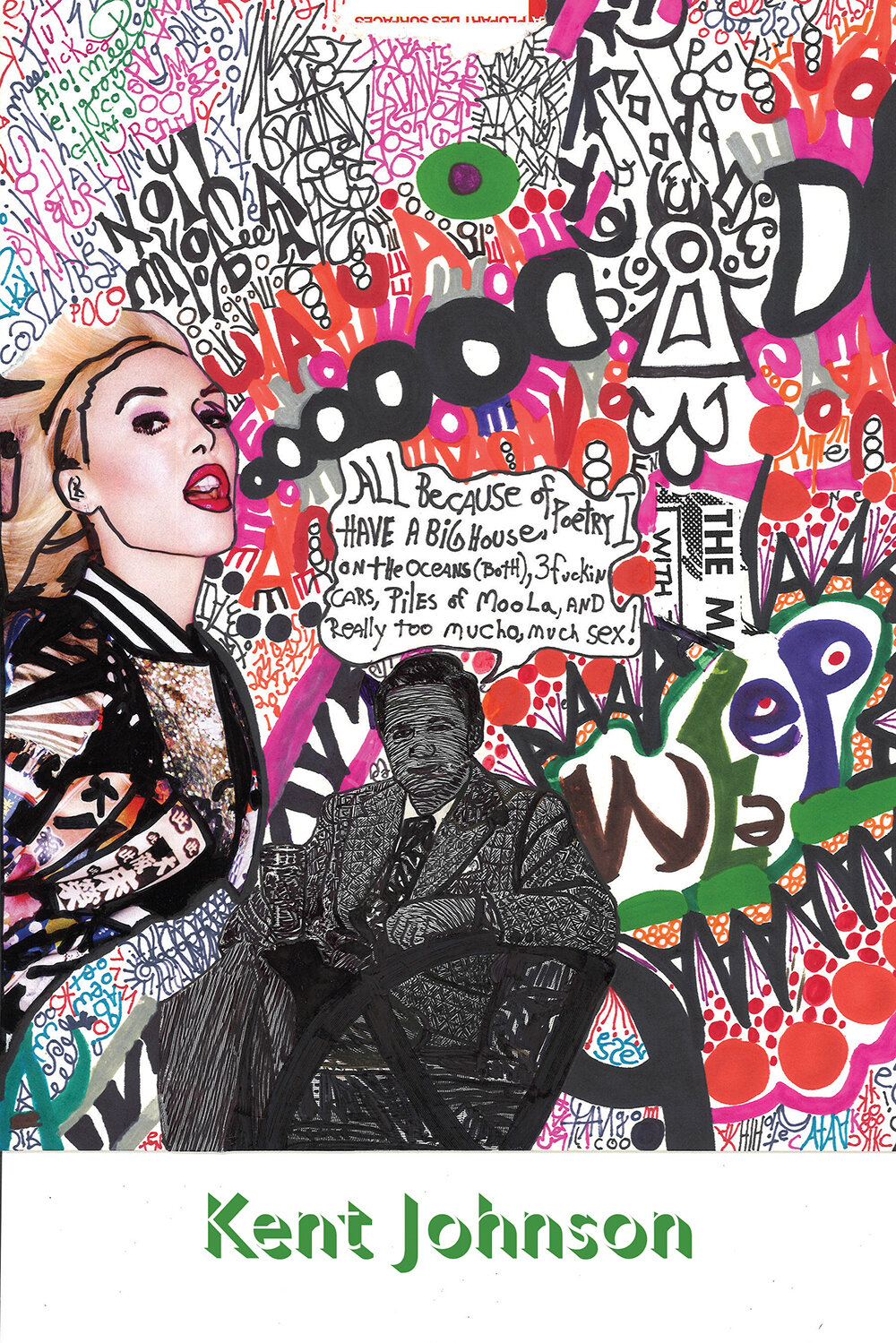

Cover of Kent Johnson’s Because of Poetry I Have a Really Big House.