Interview with Boyd Rice

The following is an edited transcript of a conversation between Stefan Hain and Boyd Rice that was broadcasted by Caesura on Montez Press Radio on July 23, 2020. A recording of that broadcast is available here.

We got into contact because Laurie Rojas, an editor at Caesura, covered The Banned Exhibition in 2019. The exhibition opened in Oslo in 2020, after being cancelled in New York in 2018. Were you surprised that those large abstract paintings of yours caused such a stir?

If they had caused a stir, that would have been just fine. The problem is that nobody ever saw those paintings, the show was shut down before anybody even knew what was in there. They just heard that I had an opening that night, and they ganged up on the gallery [Greenspon Gallery] and said that if she [Amy Greenspon] went through with the exhibition, they would ruin her life, and her name would be mud in the artworld. She was just terrified, she had never dealt with anything like that before.

Boyd Rice, Untitled. 2020. The Banned Exhibition. Galleri Golsa.

I was kind of surprised since I had a one man show in New York City a number of years before and didn’t have any problems. I had a book signing at The Strand bookstore, which is huge and was high profile, and I did not have problems with that either. A number of other shows too. And people tell me: “You know, people in New York are too sophisticated to worry about stuff. Nothing shocks them, blah blah blah...”

But the paradox about these people is that they’re militantly liberal, and yet their liberalism seems to have a strong authoritarian bent to it. I’ve never wanted anybody to be censored. I’ve never wanted anybody’s shows shut down, and it’s weird for people to think I’m a tyrant of some sort, to think that’s the way to deal with me.

Let’s spend some time with your art. When did you start working with abstract painting, and how does it fit into your work as a whole?

I started doing art when I dropped out of high school. I decided I wanted to be an artist when I grew up. So I was already studying the early 20th century avant-garde artists: the Futurists and Dadaists and Surrealists and things like that. I began reading all their biographies and all these histories of 20th century art, and I started doing oil paintings. And I can draw well, but it didn’t matter how good the paintings came out, I was dissatisfied with them because they were just a product of my mind, sort of a product of my personal taste, and I wanted to do something that went way beyond that. So I came up with the technique for doing these paintings. I was doing experimental photographs at the time and the technique I used to do those sort of suggested to me the technique to create these paintings. And it fits into the rest of my work because I think most of my work is very abstract and open-ended — that it’s evocative and sort of bypasses the mind and appeals to the instinctual side of man, the imaginative side of man.

How do you think your work relates to the art of Darja Bajagić, the other artist at The Banned Exhibition?

Well, the way I see it is that Darja uses imagery that’s very personal to her, and I try to do things that are absolutely impersonal. I try not to have them be a byproduct of my taste, or my interest, for the most part. But I think me and Darja were paired together because we were both seen as being the same type, outlaws or renegades or something. So I love Darja, and we get along great, but in terms of our art, I don’t think there’s much common ground.

Apart from painting, you’re also well known for your music. What was your background for making music? You said in an interview that you were moving around the fringes of the punk scene but were never a part of it. So what was that scene like in the late 70s, of which you never really were a part?

A bunch of us used the punk scene. For people like me and Throbbing Gristle and others, our early shows were all in art galleries. And then when the punk thing happened, we found out we could go into a real rock and roll venue and do essentially the same thing we’d been doing but get paid for it, so that was a big thing. I was doing music well before punk and I just wanted something to listen to, and I thought: why don’t I apply the same ideas I applied to painting and photography and see if I can create music that sounds otherworldly? And I did and liked it, and when punk happened it sort of changed what I was doing because I altered it to be appropriate for live performances. And so it got more into a song format. Although it still really wasn’t appropriate for most live performances because I was opening for punk bands and people were showing up expecting rock and roll, and they got a wall of noise. There were frequently riots and beer glasses smashed on my forehead and things like that.

But that scene, the scene in California was actually quite interesting because people in the United States really didn’t know what punk rock was supposed to be, so all this stuff got slipped in that was really interesting and unusual. And there were bands like the Screamers — they were a punk band that did all synths, and they were really good. A band called the Deadbeats that were kind of Captain Beefheart meets punk. There were some interesting groups, but I thought the scene as a whole was just pitiful. It seemed like fake rebellion, their counter-counterculture. Everybody was trying to be more badass than everybody else. But they were all kids from the suburbs, nobody was a badass, you know.

Since you touched on it already, how did you situate yourself in this 80s counterculture music scene, because you have worked, as you mentioned, with members of Throbbing Gristle, also Death in June and Current 93, who were famous in industrial and neopunk music. How do you look back on the formative moment of what’s now considered “industrial” and “new wave”?

I look back on that as some kind of golden age, because all those people, we were all best friends, and they were all people who I thought were doing the most interesting music on Earth. We all had a very shared point of view about the world, and most of those people came out of having a background interest in the occult, so we had that in common. I got into the occult when I was 13 years old, and then to be in my early 20s and meet all these people with similar interests was just great. We were all best friends, and at the time I thought to myself: this is a very magical moment, but it’s not going to remain like this forever. Some of them have falling outs, they’re gonna go their separate ways. I’m still in touch with a lot of those people, not all of them.

While your music does pay respect to some of the transcendent psychedelic sound of the 60s, it seems that you and your fellow travellers were more interested in the socially unaccepted aspects of the human condition: aggression, dominance, destruction, or hierarchy. To what extent did you want to break free from forms and ideas of the 60s hippie counterculture in your own artistic enterprises in the 80s?

Absolutely. I wanted to break absolutely away from that. When that was going on, I was only 12 or 13, but even at the time I saw that it was weak. I felt that the fuzzy thinking of the hippie movement was like Christianity on crack — or Christianity on LSD would be a better way to put it. Because it had those same ideals: peace, love, brotherhood, and all that crap. That has never happened and never will happen.

Whereas punk rock came along and wanted to be a reaction against the hippie ethos. It was too reactionary. I think all the people in the industrial scene wanted to rise above that, but we wanted to do it in a way that was a bit more intelligent, and make it something that was more self-contained. I think we realized that dominance, aggression, and hierarchy have always been a part of life, and if you pretend they don’t exist, they’re going to sneak up and slap you in the ass when you least expect it. If you realize that the world is a place that’s very harsh at times and even ugly, then when the worst happens, you’re kind of expecting it.

And I think there’s a whole shadow side of life. Because of the Christian duality people reject our stuff and say it’s not supposed to be that way, and go toward the light. But I think if people could come to terms with the shadow side there would be more...what’s the word I’m looking for?

More of an integration?

Yeah, absolutely.

In the 80s, you and your fellow artists such as Throbbing Gristle provoked people with topics that were considered — for lack of a better word — perverse. Yet subjects like sadomasochism and non-normative gender identity such as Genesis P-Orridge’s today seem much more accepted with mainstream audiences. What do you think about this?

It is hard to believe, but in the late 70s or 80s Throbbing Gristle put out a single called “Something Came Over Me,” and it was a song about masturbation. At that time, most people, even in the punk rock milieu, wouldn’t admit that they masturbated. When the single came out everybody was making fun — “we always knew Throbbing Gristle were just a bunch of wankers.” So that’s how much things have changed.

And the punk scene in California certainly was very very macho, very homophobic, and people today wouldn’t admit that it was that way. But I knew a guy that was the singer of a band, and his drummer was a friend of mine named Tom Rashan. And this singer was just humiliated that he had a fag as his drummer. Tom was a good drummer and a great guy. It is hard to believe how much things have changed in the past 50 years or so. Mostly for the worst.

You have often dealt with popular culture. It’s said that the beginning of your musical creation lay in the fateful meeting of bubblegum pop culture à la Little Peggy March with mid-70s tape machines. In 2004, you were also one of the founders of the infamous UNPOP Art group, pushing pop art to its extremes. What relationship does your art have to pop culture?

A lot of my art doesn’t have anything to do with pop culture. But I grew up in the golden age of pop culture, and it impacted me. Recently, I did a series of Pop Art colleges where I took various documents and photographs signed by extremely famous people to create a juxtaposition between the two figures. I had a Brady Bunch comic book signed to me by Marsha Brady and superimposed over it the autograph of Linda Lovelace, who, you know, was in Deep Throat. Their handwriting looks virtually identical. It’s like this frilly little girl handwriting, and they both drew hearts along with their signatures! It is one of these things that you can’t look at it without imagining Marsha Brady sucking cock. What else are you going to think of when you look at something like that?

I like those things too because I like the feeling of looking at autographs. When you’re looking at this thing, you know that the human who signed it was one time exactly that close to it — you almost feel like you’re filling the same space as these historical figures. I did a bunch of those, Charlie Manson and Annette Funicello autographs, Andy Warhol and Ian Brady, the Moors Murderer, and they both said the same thing. The Andy Warhol autograph said, “Merry Christmas, Andy Warhol” — it was just this photograph of people lying on the beach, — and then I had a Christmas card that Ian Brady had sent me, “Happy Holidays, Ian Brady.” So the world’s most famous murderer and the world’s most famous artist, both in the same spot.

There’s a very Surrealist quality to that. I also thought about some of your musical work about Italian Futurism’s sound experiments. Is your work for the avant-garde, or for the masses?

For both. I think most of the masses won’t understand it or won't like it. But I’ve found it much more satisfying to do work for ordinary people who aren’t expecting anything than for the people who come to an art gallery expecting maybe to see something shocking — and when they’re presented with that, they just sit there and are thinking of the possible subtexts and symbolism and all that shit. An ordinary person comes into a club where they’re expecting to hear rock and roll music, and they hear an overwhelming wall of noise, and they don’t know what to say. But a lot of them like it, because it’s very visceral. It’s not like you're just sitting as a spectator. You're experiencing something.

What title do you think fits you better: “the world’s most dangerous artist,” or “the world’s most original prankster”?

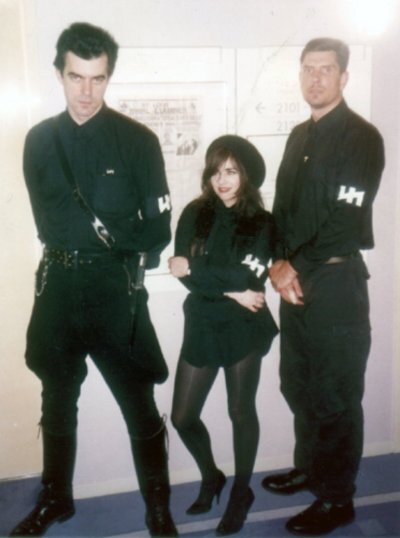

Rice with Rose McDowall and Douglas Pearce of Death in June in Osaka, Japan, 1989. LastFM.

Well I’m still very doubtful that art can be that dangerous. I know that people in the artworld think that art can be very dangerous, revolutionary, and is going to change the world. I have my doubts. I don’t think any of my art is terribly dangerous. The prankster thing I mostly did when I was a teenager and in my early 20s. And I sort of did it at the time as a form of psychic warfare, to see how much I could get inside people’s minds and change them around, and make them believe something that would cause them to do something else. Because from the time I was a child, I just assumed I was gonna have to be a criminal when I grew up, since I knew I didn’t want a normal job like everybody else. I was walking to school one day in the third grade, and I saw a man through the window of his house ironing his shirt, and then he put his shirt on and buttoned it up, went into the kitchen, put a sandwich and an apple into a brown paper bag, and then he went out, got into his car, and headed off to his job. And I just stood there thinking, “Ah fuck, that’s what adulthood is going to be like. It’s not going to be this thing where you can do anything you want. You’re gonna have to do this boring stuff and go to a job every day.” So I made up my mind then and there, “I’ll do whatever it takes not to have to live that life. I want to do something far more interesting.” If I have to rob banks in order to do it, that’s fine. I was preparing myself for a life of criminality of some sort, but it never quite happened.

You once said that when it comes to art, it’s all about context, and you’ve been criticized for your artistic use of symbols, with the quotation of Nazi symbols or the deliberate alienation of liberal symbols. I’m thinking here about the “Victimhood is Powerful” shirt, for example. What was the context for your use of these symbols?

I don’t know that that’s altogether true. I used the rune symbol which was also used by the Nazis, but I don’t seem to recall using too many Nazi symbols. I certainly never used the swastika. But I think you’re taking my comment about context out of context. When I talked about that, I was talking about the artworld vs. the real world. When you do something within the context of a gallery, it ceases to be real, and it becomes symbolic, so it doesn’t have the same sort of impact on the audience.

I was at a lecture series at Massachusetts Institute of Technology once, and all the other people were professors, of philosophy, of art history, etc. We were leaving MIT to walk across the street to our hotel, and they were talking about all this great potential of art. And I presented them with that idea that the context of the artworld sort of makes everything impotent and intellectual. There was a guy, really well-known in California in the 70s, and he would go into university classrooms and he would take his pants off, smear horrible stuff all over himself, put whipped cream all over his erection, and shove a Barbie doll up his ass. And all the while, wearing this ugly old man mask. You’d see the pictures and it looked unbelievably hideous and crazy. And I said, this guy went into universities to do this, and the students just sort of sat around and contemplated it. If you were waiting for the light to change, and a homeless man was doing the same thing, you would remember that for the rest of your life. And the college students who saw it, because of the context of the artworld... it rendered it essentially meaningless.

I guess that’s where I was going with my question. Because in a lot of 80s music there is the reusing of totalitarian symbols, not restricted to Nazism. I’m thinking of Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft, who in one song called for dancing Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin. What about this idea of alienating those symbols of totalitarianism to point something out about them?

Rice performing in the 1970s. WFMU.

I don’t know. I think you’re conflating me with what a lot of other people were doing. I think Throbbing Gristle started using the totalitarian images, and then all of a sudden, everybody jumped on the bandwagon. So it was just gratuitous; people would release tapes with gratuitous pictures of piles of dead bodies at Auschwitz or Hitler or something and the stuff that Genesis did very thoughtfully, all the other people that copied him did it quite thoughtlessly. It’s just like, “oh this is a shocking image, we'll use it.” But the totalitarian thing is, whether it’s Stalin or Eva Peron or Mussolini, that it appeals to something in humanity because there’s a strong element of show business to everything. There’s show business to organized religion — they have their sound rituals and incense, and in the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany they had these similar ritualized ceremonies. So that’s what appeals to people about that sort of thing, but realistically, most people who use it did it mindlessly. I mean Laibach I think understands what they’re doing, but not most people. There’s a saying: “The first person to do something is a genius, the second person to do it is an idiot.”

Would you consider yourself an apolitical person?

Genesis P-Orridge performing with Throbbing Gristle. Photograph by Suzan Carson/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images. Revolver Mag.

Apolitical is right. I’ve always been absolutely apolitical because it goes into what we were discussing earlier. I don’t expect the government to do anything to make my life transformed. I know that if I want that done, I have to do it myself. Political systems are fairly identical all over the world, no matter how much they seem to be different from one another. They’re all basically the same thing. Salvador Dali got along great under Franco, and Ezra Pound got along great under Mussolini, and I get along great under whoever’s in office here. I’ve always had a great quality of life, even in the worst of times. In the 70s, when people were lining up to get gasoline, it was the worst economy we’d ever had. I was living my life the same way I always had.

To return to the “ Victimhood is Powerful” t-shirt, is there any connection between that and what you’ve mentioned before, William S. Burroughs saying that language is a virus?

Ezra Pound saluting. TLS.

No. That t-shirt was inspired by the #MeToo movement. Everybody wanting to be a victim: “Oh look, I’m a victim too.” There’s a certain segment of the population for whom being victimized is the ultimate form of heroism, and I don’t understand that. I guess it’s easy because how hard it is to be a hero, how hard it is to be brave and do something tough. But it’s easy to say, “Oh look at me, my life is miserable, but it’s not my fault. I’ve been victimized by this group or that group or men in general.” So I just took that from the old women’s movement slogan “sisterhood is powerful” and I thought, oh well today “victimhood is powerful.” Because as soon as you go on the internet and say, “I was raped,” everybody says, “Oh poor thing.”

In an interview, you said that at the time of your youth in San Francisco, if you had a girlfriend, you were homophobic; if you were for Reagan, you were a fascist. I hadn’t even been born back then, but that sounds somehow familiar to me. What do you think is the main difference between the era of Reagan and the era of Trump?

In the Reagan era, most of the insanity came from the lunatic fringe. Only old hippies or punk rockers were the kind of people who would say, “Oh Reagan’s a Nazi.” Like my friend Jello Biafra, he was always on about how Ronald Reagan was a Nazi. Now, Ronald Reagan was not a Nazi. That’s just ridiculous. Whereas today, the people calling Trump a Nazi are half the population of the US. Today that insanity of the lunatic fringe constitutes popular thought and popular opinion.

We are living in times of a global pandemic, and now as we’re recording this at the beginning of June, there have been riots in the United State over the last few days. Do you have any comments about this situation? It feels bizarre, that’s why I’m asking.

I’ve been saying for years, I think there is a feeling amongst people who didn’t live through the 60s that, “Awh man, we missed out on the 60s at Kent State and all those marches. You know, teenagers changed the world...” There are just a lot of people in that mindset and a lot of people who just want to go out and burn places down.

A friend of mine is a cop, and he was called out when these protests and riots happened. At a lot of these things there will be a bunch of peaceful protesters, and then a line of buses will pull up with protesters from out of state, and those people actually are the ones who cause most of the trouble. And if the rowdy people go and smash a bunch of windows, those who have never smashed windows in their life are going to go out and do the same thing, and when people see somebody running off with stuff for free from a store with a broken window, they feel empowered to do it. Then if the cops aren’t there to keep order — which they aren’t — they’re just gonna keep doing it. Last night or the night before, people were looting Target stores, I don’t know if you have Target stores in Germany.

No we don’t.

You know, mediocre stores that sell a little of everything. So people were looting those, and I heard that they went up into Midtown, and some guy smashed the windows on the Rolex store. And before that, people were stealing Nike shoes. How many Nike shoes can you carry with you? Not that many. But if you go into a Rolex store and you get all these watches that are worth $25,000 apiece and fill up a pillowcase with them, that’s efficiency. The person who decided to loot the Rolex store, he gets a gold star for going above and beyond. //

Rice wearing “Victimhood is Powerful” t-shirt. @boydriceofficial.