Anvil and Rose 14

Études by Friederike Mayrocker, tr. Donna Stonecipher. Seagull Books, 2020 ($24.50)

Maybe the upside-down photograph of roses on the cover is a warning. And the epigraph: “and I hate all storytelling, even in novels,” credited to a Jean Paul. Études offers sort-of-prose-poems, sort-of-diary-entries, sort-of-sensitive-verse, each piece dated, promising intimacy, but remaining hermetic, cryptic, elliptical. Here’s the opening line of the first piece: “and everyone asks, what are you reading these days &c., while the little skull = little bird bill on the doormat.” The frequent use of “=,” and “&c.,” and “ach” (“Tinsel your hair ach your silvery hair”), and ellipses (why eight?), and plus marks (why ten?) all contribute to the sense of a closed, private text. Not to mention the use of underlining and caps. At times the repetition in the book can be effective, but it’s too often broken with “ach,” or “&c,” or an allusion (“we float through the lianas – BATHHOUSES of D.”). It’s as if an extensive annotation for each text is sorely needed. This reader is left saying, with the author, “bewildered am I,” and yet wishing, with the author, it would be possible to say, “I am spellbound in your midst” (author’s underlining). Leading to an outburst of “ach = . . . . . . . . ++++++++++ &c &c &c.”

Pierre Reverdy, ed. Mary Ann Caws. NYRB, 2020 ($16.00)

This bilingual selection of Reverdy calls on the reader to reassess his work, and it’s a pleasure. Reading Reverdy is a bit like studying a Cubist painting with the magnifying lens feature on the internet: Each line in his poems offers an angular perception. Take “False Portal or Portrait”: “In the unmoving space / Within four lines / A square for the play of white / The hand which propped your cheek / The moon / A face illumined / Another’s profile.” No wonder John Ashbery translated Reverdy, given his interest in the visual arts. Here’s the opening of “A Lot of People,” as translated by Ashbery: “Trembling the minutes shine at the tips of the branches / Night’s black peacock proudly spreads his tail / The stars turn to watch.” It’s fascinating to think of Reverdy’s influence on Ashbery, along with his possible influence on some of other translators in this collection: Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Rexroth, Rod Padgett (who translated many of Reverdy’s prose poems). For anyone interested in the intersection of Cubism and French Surrealism, and who wish to ponder what this conjunction has conjured on American poetry, this volume is a must. Soon you’ll be seeing visions of Night’s black peacock and saying: “O Pierre! O Reverdy!”

Selected Poems by Frederick Seidel. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 ($30.00)

Frederick Seidel wants to shock you — and not just with the price of his Selected Poems. He wants you to gasp, squirm, and kick the cat about lines like: “rap, the rhyming slave-rebellion app,” and “Feminists in nylons in his brain stem. / Escaped slaves recaptured. They crave men,” and “Why not hate? Why not exterminate? Why not violate / their rights and their bodies?” Critics call this “sophistication, nerve and skill.” Claim that “he radiates heat.” That he is “the new kind of visionary.” This heat-radiating, sophisticated visionary has this to tell us: “No one was getting out of this alive.” That’s new? About a dead dog, he utters the profound: “you were just a dog.” And he has so much to tell us about women: “When I see your tits on FaceTime I see stars.” Seidel seems to think that the more brutal the insult, the more evidence we see of his literary skill, like a dentist who can’t stop bragging about his diamond drill. Then, he hopes, the reader will swoon in a fit of endearing outrage. Charmed, the reader will come back for yet more of his sophisticated insults. Apparently, no one has told Seidel that when you rely so much on shocking the reader, you risk producing intense bouts of (yawn) boredom. In fact, right now the inspector feels a great need for a sophisticated nap.

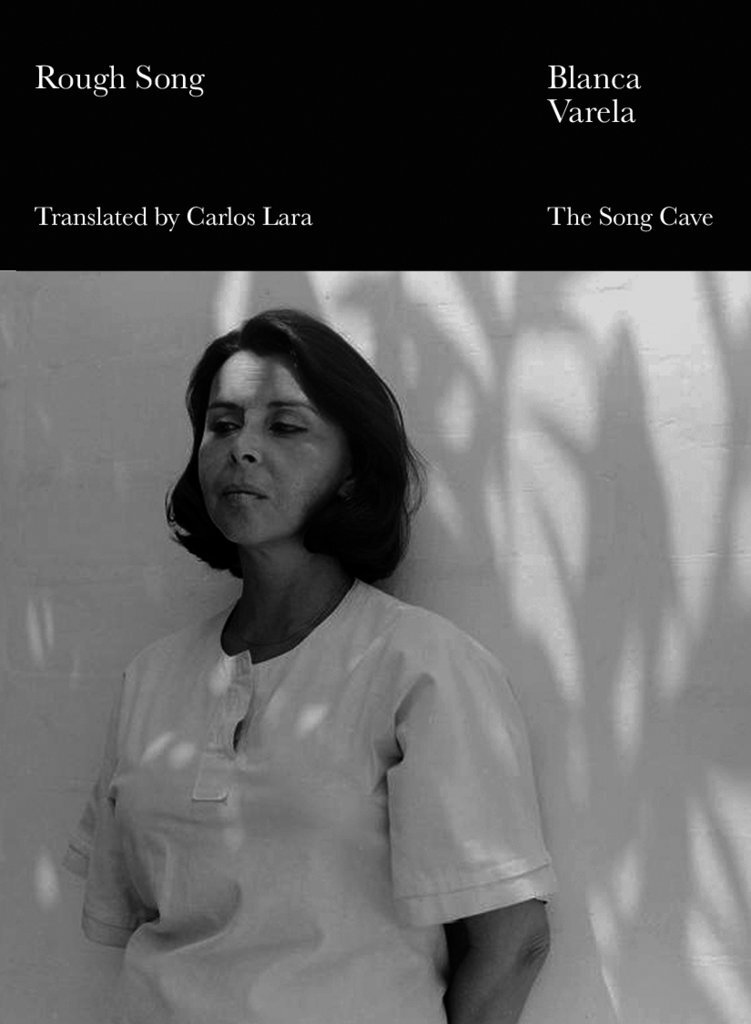

Rough Song by Blanca Varela, trans Carlos Lara. Song Cave, 2020 ($17.95)

Some poets tell you more than you want to know, or make it up, if their miseries are not enticing or shocking enough. Other poets lurk in the shadows, making you want to know more. Varela (1926–2009) is one of the latter. Here’s her goofing on the issue of her identity, in a four-line poem titled “Identikit”: “yes / the dark matter / animated by your hand / it’s me.” And just who is this mysterious “me”? She hung out with Breton, Sartre, Michaux, Beauvoir, Giacometti. She won the Octavio Paz Prize for Poetry and the Federico García Lorca International Poetry Prize, yet this bilingual edition is her first work translated into English. Carlos Lara does a skillful job preserving her “dark matter,” as can be seen in this excerpt from “Speaking Softly”: “I have yet to arrive / I will never arrive / in the center of everything is the poem / intact sun / inescapable night.” Varela loves paradox; she’s both “will never arrive” and “in the center” of the poem, like Emily Dickinson wearing a balaclava. All the truth at a surreal slant.

The Sunflower: Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void by Jackie Wang. Nightboat Books, 2021 ($16.95)

Couldn’t we all use a spell right now to save us from the void — or is it multiple voids? Anyway, it’s hard not to feel the promise of such a title. But these spells feel less than magical: “I dream I mutter / Capitalism is not a bed of sunflowers / as I hobble around Wall Street / in broken high heels.” This flowery definition of capitalism induces in this reader an “OK, and so?” As do other dreams that feel less like dreams than symbolic moral lessons: “Instead of opening doors and walking through them, I smash windows and glass walls . . . . Now there are many of us who carry axes and never wait to be let in.” You can almost hear the author applauding herself. While the use of dream situations allows the author to at times sidestep such easy posturing, the voice in the book further muddies the poems. A mix of childlike (“I don’t want my butterfly to die. Ever.”) and adult (“the execution of reckless adjudication”), the voice is not helped by the childlike / childish drawings by Kalan Sherrard, making The Sunflower feel like a private journal, written for an audience of one — the author. “The world will be seen through my wound-colored glasses,” we are told. OK, and so? All writers see the world through a subjective lens, yet these “wound-colored glasses” take subjectivity to an extreme, creating a kind of void that the subtitle promised to rescue us from.