CRITICISM

ESSAYS

“Kierkegaard wrote a marvelous thing in Either/Or. He said he feels that when he dies, they are going to ask him only one question, when he gets up there. And the question is, ‘Did you make things clear?’”

Do we know what film is about today? The ersatz cinema which fills theaters seems to tell us definitively: No. Stone’s film is much more than a cultural product of its time. It’s one of the best films of the 1990s and still has a great deal to teach us about how film works, and what it means to make a political film.

Imagine driving in your car listening to MJ on the radio, grooving and enjoying the song until … wait … you stop to ask yourself … was this bassline played manually by a human, because if MIDI sequencing was involved, I don't like it anymore. Said no one ever!

Although there's a reaction against utopian thinking, art itself has a utopian edge

Now seems as good as any moment, as history breaks around us, to reconsider our attachments to modernism and formalism — along with the implications of such attachments — for the purpose of developing an art criticism that aspires to be adequate to the present.

What is really feared in loud music is not the loudness, but the ugliness

Our art education does not produce artists or critics, but little art historians – worse, librarians! We are what Nietzsche described as “idlers in the garden of knowledge,” individuals with an Alexandrian relationship with art, art as an infinite archive of “works” to be perused, art as mere culture. Our spirit transforms art into artifacts.

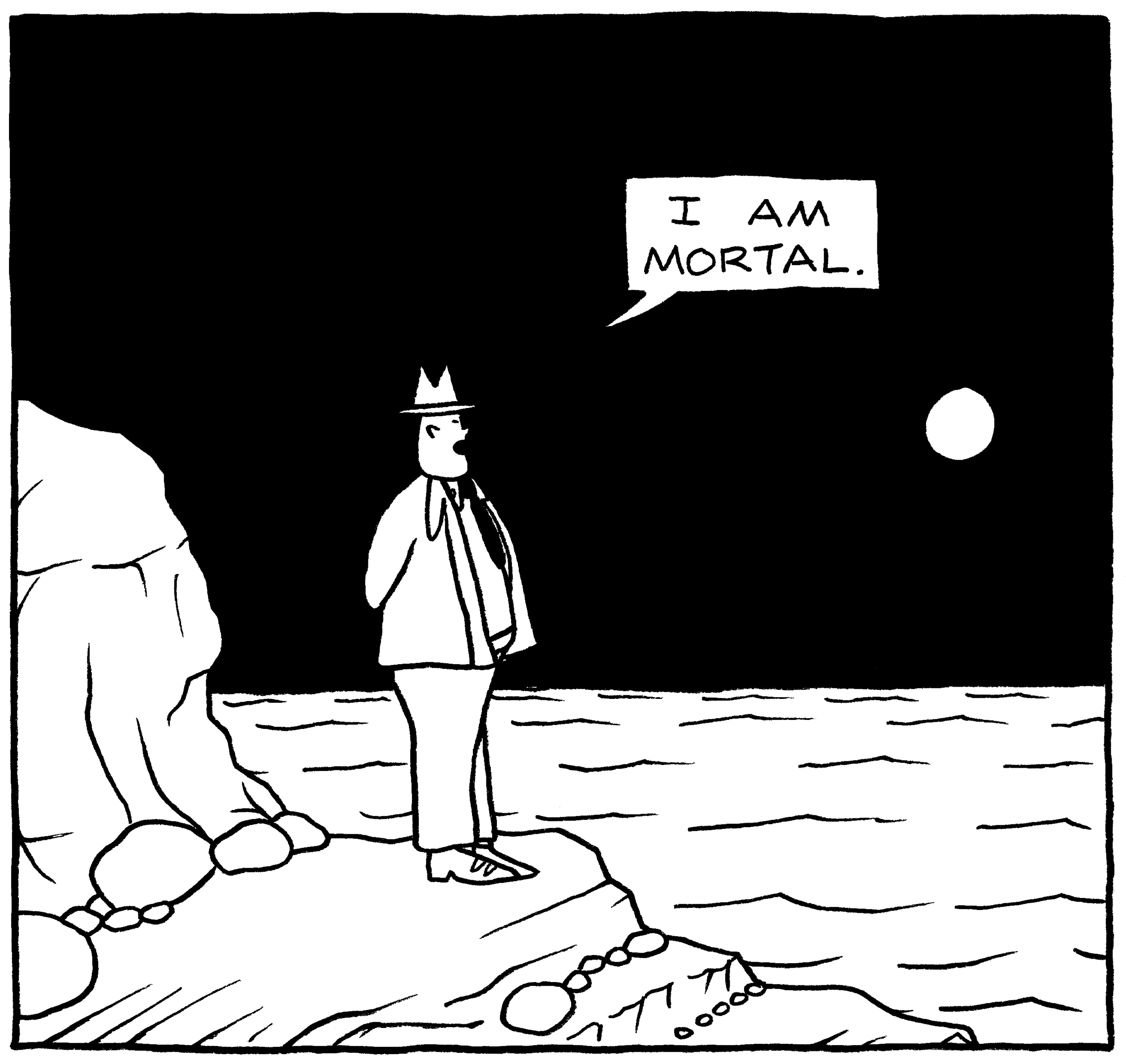

Art occupies a precarious position in society. The artist even more so. One the hand, art is officially sanctioned. It is generally taught, and ‘creativity’ and ‘self-expression’ are almost universally encouraged . . . But the true artist, as Octave declaims in his eulogy on the rock, knows that he “is a misfit, a stranger, a prophet none believe, and to whom none relate.”

There are paintings, and then there are paintings — I’ll capitalize the latter. Anyone who has Seen a Painting will feel the Truth in this distinction, and anyone who has felt the dissatisfaction of merely seeing a mere painting — and who hasn’t? — will either suspect that such a distinction exists or turn away from the work in front of them in search of meaning elsewhere.

The musicians’ interpretation of the song seems to combine tradition and modernity, with the brass band itself representing tradition and the adapted song representing the modern, contemporary. However, the brass orchestras appear oddly out of time, unintentionally comical. They seem to be enacting the funeral of what they represent—the postal service as a state enterprise, tradition, and society before globalization. Yet, for centuries, the postal service symbolized progress, innovation, and renewal.

If the forced collision of dramatic characters and public situations is understood as a metaphor for art, then according to Mailand / Innenhof, art’s role seems to be that of a troublemaker. However, the “theoretical and practical creation of situations,” which echoes a situationist self-understanding, doesn’t only target scientific or political events. It also aims at the so-called cultural sector, and thus at itself.

REVIEWS

These poems remind us how the literary past is always waiting for us in the literary future…

Most viewers, upon encountering Lamar Peterson’s work, will go no further than to subsume the paintings under the generic category of “black figuration.” This is to be expected; most people don’t care enough about art to actually look at it (whether they admit it to themselves or not).

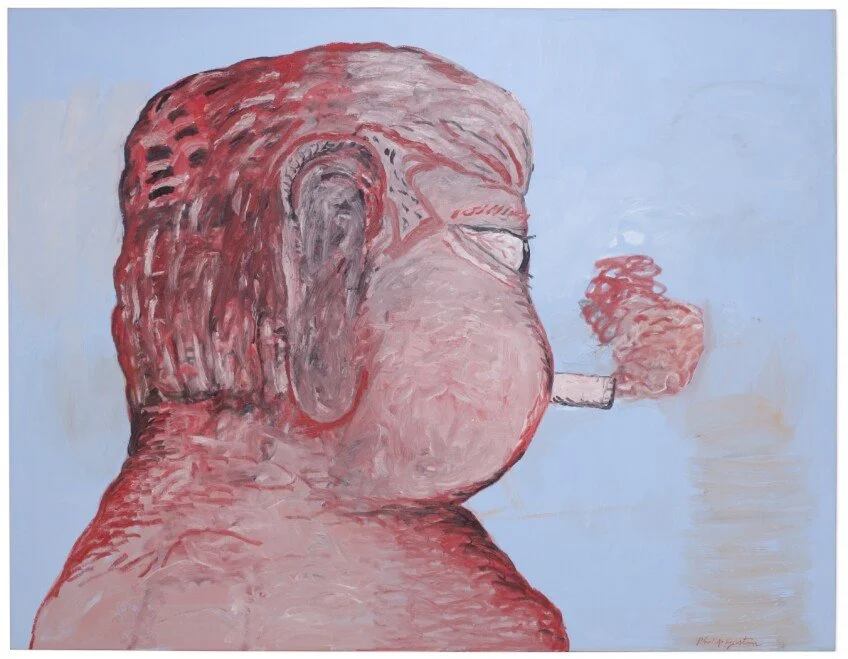

It is the complexity of emotional registers, the playful ambiguity towards content, the energy of her formal immediacy, and her willingness to lean into the grotesque which together form the magnetism of her works.

In an art landscape populated by chalky paintings made by people who don't care enough about their medium to learn how to use it, crowded alongside paintings based on photos by people who think paintings are just images, it shouldn't be surprising that the gallery-going masses are titillated by a painting with a nice surface.

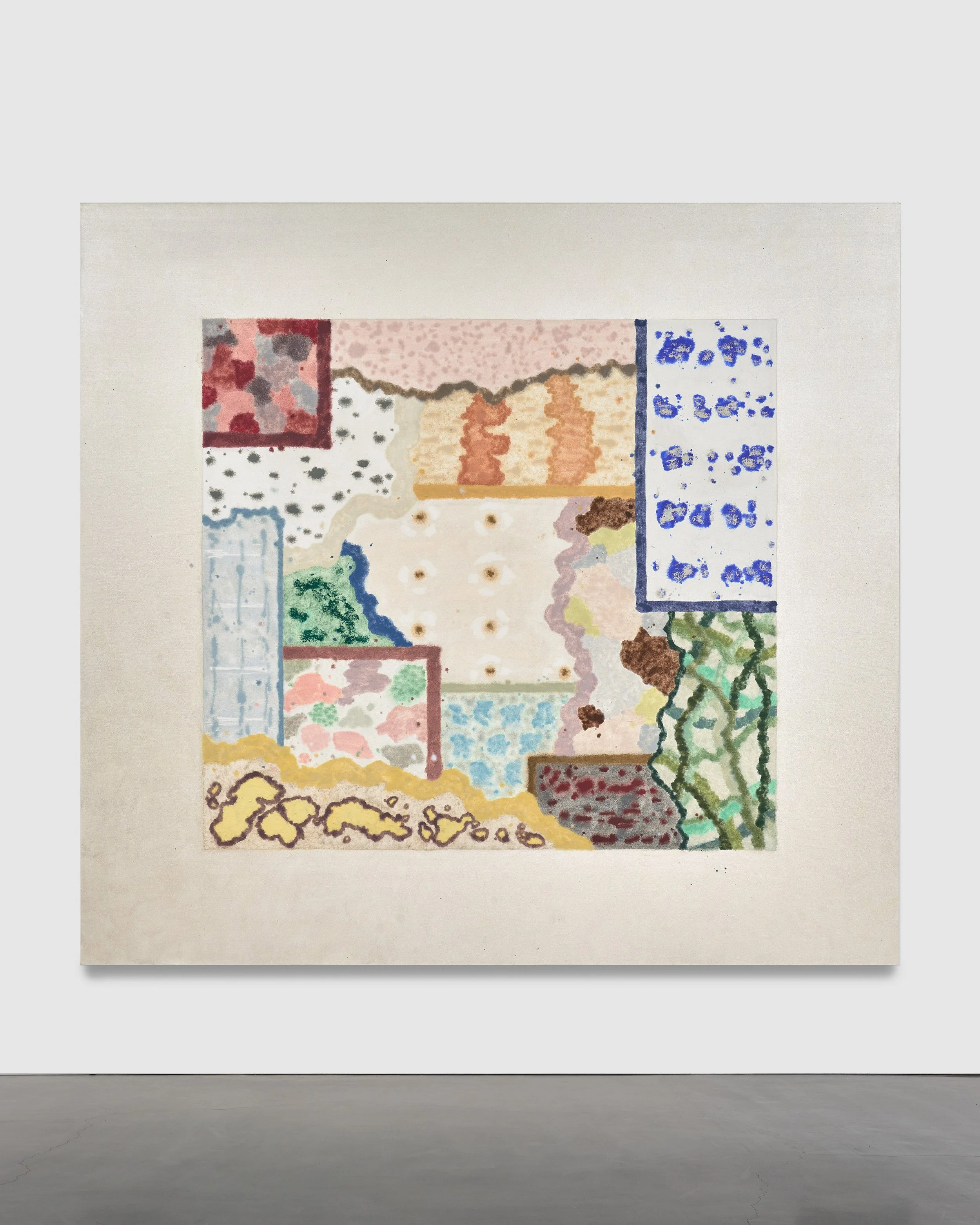

Rebecca Morris’s current show at Regen Projects, titled simply #34, after its place in the sequence of solo shows that constitutes the artist’s career evinces a painter who, having reached a certain stage of maturity, looks to take stock of the work she’s produced. How does it reflect her understanding of painting? What has held up and what is yet to convince?

Plantasia is a two-day ambient music fest held in Chicago named after Mort Garson's 1976 record, Mother Earth's Plantasia.

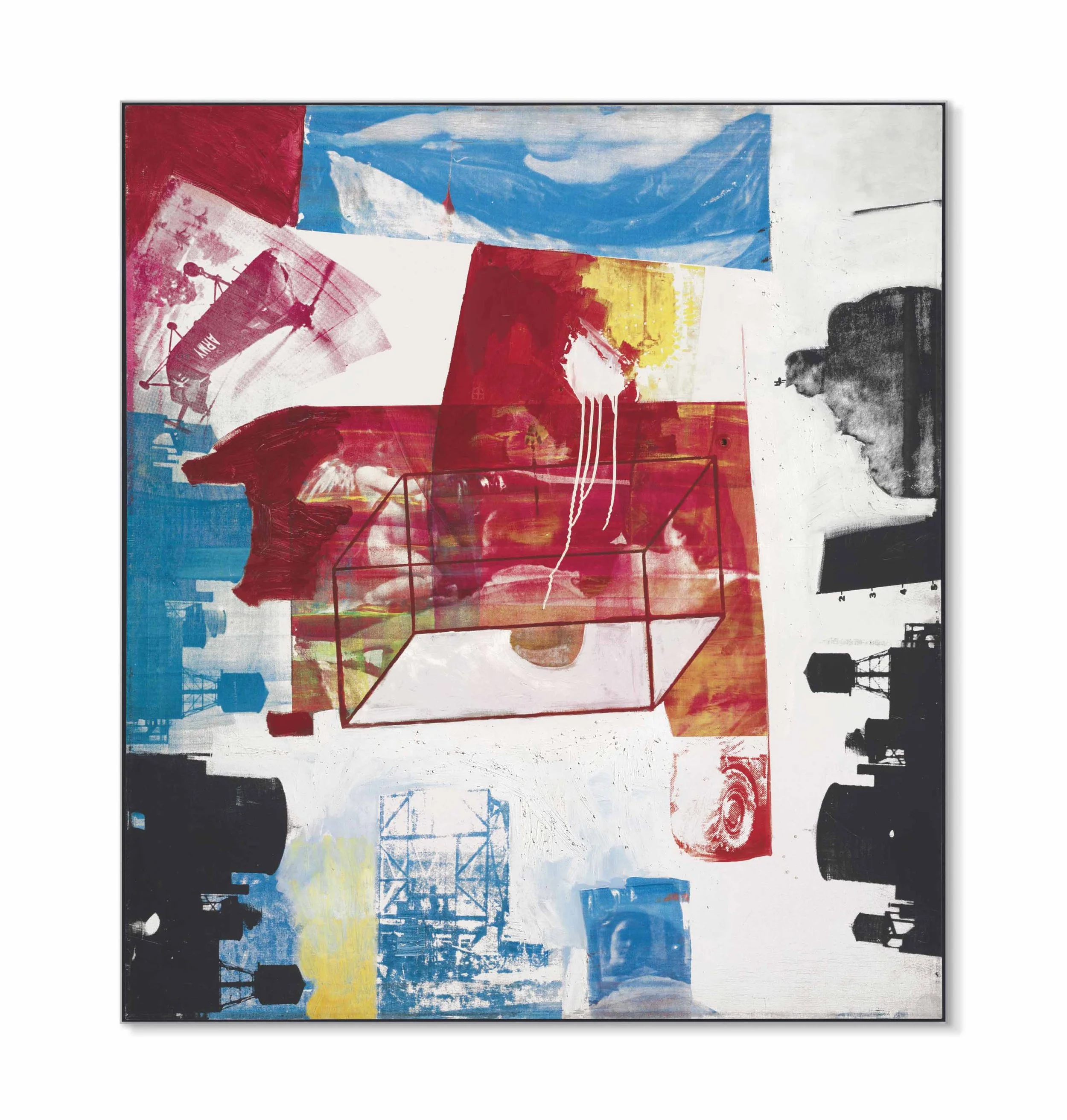

The further one surrenders to the compositional dynamics in each work, the more archetypal or elemental they seem to become. They are classically modernist in this sense, distilling form into an essential image, a snapshot of a prototypical aesthetic idea. This seems resonant with the glyph theme in their titling. Juxtapositional interventions — in this case Hurley’s sticks — resolve into a formal irreducibility.

I penned the bulk of this review on the back of conversations with friends when we watched the film after it came to Hulu in the summer of 2023. But I sat on it, convinced that no one in the broader public had seen Chevalier — or ever would.

“I’m not fit to be a mother. There’s something else I’d have to do first — to change myself from a doll to a real human being.” With these words, Nora Helmer (Sarah Wharton) leaves her husband Torvald (Stephen Dexter) at the end of Royston Coppeneger’s new translation of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House (2024).

Often, you'll hear a painter mutter enviously while looking at a painting something along the lines of ”Damn. He just did whatever the hell he wanted.” Variations of this phrase were doubtlessly uttered many times over the last month throughout the adjoining galleries of David Zwirner’s 19th Street location, where Raoul de Keyser’s paintings hang on the walls, their apparent haphazardness inoffensively contrasting with the sky-lit gallery space.

DISJECTA MEMBRA

Philippe Jaccottet’s 1981 essay on Osip Mandelstam, with poems translated by Matvei Yankelevich and John High.

Politically, melancholia may be more destructive than idealism, but aesthetically, doesn’t melancholia, as a kind of negative idealism, seem almost natural?

Victor Cova introduces a 1941 exchange between Claude Lévi-Strauss and André Breton.

Gilberto Perez’s commentary on history as seen through the lens of the filmmaker duo Straub-Huillet.

Personally, I associate Satie’s work with a feeling of the aridity that Nietzsche came to value over Wagnerism — the gentle sea-breeze in the highest mountains that wafts in from some strange land and tickles the senses with possibilities of spiritual freedom.

As the artist, reaching deep into nothing, with nothing, and only for the sake of desire, creates something great, far beyond the imagined object of desire, fulfilling and exceeding every wish in a way which could never have been fully anticipated, so too does the lover encounter the beloved.

He was not a literary artist in the sense that his work doesn’t seem to wrestle with questions of form; he’s not attempting to reinvent the surrealist modes at his disposal but rather making use of them as vehicles for his insurgent imagination and apocalyptic vision, the fury of which elevates his writing above and beyond the mere assemblage of irrational word combinations.

When I looked up Barrax’s collections, I found that his work spans not only relatively traditional-looking lyrics, but formally experimental poems that disarrange syntax and disperse words across the page.

After a century of deafness to the task and ambition of music, composers may need to relearn how to learn before Schumann’s words can even begin to make sense. How can the music of the past free the music of the present?

Jack’s poetry asks you, the reader, to abandon yourself, to engage with what you don’t know, and can’t understand, and enter a path of transformative gnosis.

INTERVIEWS

Bret Schneider delves into everything from Indian ragas to Bach’s recreation of the mind with composer and pianist Michael Harrison.

Bret Schneider speaks with composer Katrina Krimsky about her career spanning half a century.

“I wanted to connect to people who were like-minded but also saw this as a new frontier with a lot of possibilities for art making.”

Bret Schneider and Omair Hussain discuss musical composition and their albums Drunk Walks and What Goes Away.

“Film is, for me, an art of composition.”